Publications

Future Imperfect

Monira Al Qadiri: The Saudi New Wave | Digital Landscapes and Future Institutions

Vladimir Bukovsky once summarized the Soviet Underground – Samizdat – using the following statement: 'I write it myself, censor it myself, publish it myself, distribute it myself, and spend jail time for it myself.' Indeed, Samizdat literally means 'self-publishing' in Russian. Samizdat existed during the reign of the Soviet Union, so naturally the publishing was executed on paper, and exchanged hands in physical form.

I would like to propose that we take a leap of imagination and displace this phenomenon by situating it in the twenty-first century Arab world. The medium would not be paper, but the mobile phone screen, the discursive arena being cyberspace itself, permeating across all of its expansive, unregulated and chaotic dimensions. 2011 was a year that changed the face of this region forever – for better and worse – and part of that upheaval owed its fruition to instant communication technologies, and their ability to help people self-organize at will.

The cultural sphere was not exempt from this transformation, as the desire to self-publish ones thoughts and expressions exploded in every field imaginable: 'our lungs expanded, and we were all able to finally breathe' proclaimed one Egyptian writer so aptly at the time. The current political landscape today appears abysmal beyond belief, but the cultural sphere still thrives, despite all of the pressures and disappointments that it is constantly subjugated to.

It may seem completely baffling to some, but as someone who grew up in Kuwait, my eyes are now firmly fixated on neighbouring Saudi Arabia as the nucleus of future artistic and cultural production in the Gulf region. Saudi Arabia is arguably the most conservative country in the world, run by an absolute monarchy coupled with a strict religious theocracy. The centres of control are two-fold, monitoring and dictating up to the smallest detail of human interaction and behaviour. This double power sphere had succeeded in stifling the populace's ability to express itself for decades, rendering them almost invisible and utterly without voice. Indeed, many on the outside only see the face of the government and its actions as 'Saudi Arabia', and neglect the 30 million people living within its borders, forever relegating them to a life of concealment and secrecy. Regarding them with disdain and conceit is a prejudice even I myself was once guilty of.[1]

But today, things have changed dramatically. There is a serious cultural renaissance taking place in Saudi Arabia, but one must abandon all previous misconceptions and look at this place with a fresh pair of eyes. Although on the surface it may seem that recently the government has 'adopted' this movement by even creating an official entertainment authority this year,[2] the change very much started from the bottom up; from the darkness of uncensored and unregulated underground activities, slowly swelling to encroach on mainstream culture in the country, and eventually expanding towards the whole region. The reality is that this transformation can no longer be controlled in any rational sense of the word, so the hand of the authorities has been forced into accepting and even claiming it.[3] Much of this activity can still be situated in the realm of popular culture and be classified as 'entertainment', but the seeds of art-making, discursive thought, and independent institutionalization have been sown, and we can already start to see them taking hold, albeit still shape-shifting and under the surface in many ways.

The beginnings of this movement can be likened to Samizdat – everyone began the process of self-publishing at their own risk. Their desire to do this did not only stem from the will to free oneself from heavy official oversight, but to overcome the desperate boredom of a gender-segregated sedentary lifestyle where even outdoor sports can be deemed illegal at times, women cannot drive, and levels of youth unemployment have constantly soared for so many years. The disparate levels of wealth that the oil economy has generated coupled with religious extremism and rampant nepotism and corruption created a culture that felt like 'diseased stagnant water'.[4]

In 2005, an erotic novel written in email form called Girls of Riyadh by Rajaa Al-Sanea spurred an entire generation of Saudi erotic writers, to a point that over time Saudi sex literature has been deemed 'tyrannical' by other literary peers in the region.[5] Of course, the novel was immediately banned on release and so were its many successors, but the ban didn't stop it from spreading like wild fire on the Internet and sales of it on the black market exploded. The titillating details of girls just simply discussing their intimate lives in a contemporary manner was shocking and somewhat revolutionary.[6] With literature and poetry being the most traditional and advanced method of artistic expression in this part of the world, the novel caused serpentine ripple effects. Secret book clubs (both off and online) began to emerge in many cities around the country, and some even allowed both genders to participate.[7] 'Art is contributing to – if not leading – the reform process that we are going through now in Saudi Arabia,' said Abdo Khal, another controversial but celebrated writer.[8] Indeed, the government has also begun to reign in on the book clubs, but the culture has become too widespread to comprehensively contain.[9]

With the advent of YouTube, cheap video production and the digital-native millennial generation under the age of 30 – who compose 60 per cent of the country's population – the medium of choice quickly evolved from the written word to film and video making.[10] Saudi Arabia has the highest Internet penetration per capita in the world, so it was only a matter of time until Saudis took things into their own hands to film the stories that were important to them.

My first personal encounter with a Saudi film 'institution' of sorts was back in 2008, when I attended the first Gulf Film Festival in Dubai. I met a group of young Saudi filmmakers from Riyadh who called themselves Talashi (literally: 'Fading Out').[11] To my surprise, they were making films that tackled extremely daring subjects, from forced gender roles, to religious hypocrisy, suicide, and even rape. They were not being provocative for the sake of provocation, but wanted to show the tangible realities that they faced in their daily lives. Despite the rudimentary style of their films, and the obvious zero budget production value, their works portrayed a razor sharp reflection of their often dismal surroundings. As a result, it was only natural to hear that most of their films had never been shown in public in Saudi Arabia except in private screenings at friends' homes or apartments (cinemas have been banned in the country since the early 1980s). For example, a short by Mohammad Al-Khalif called According to Local Time (2008) depicted the frustration of a young Saudi man trying to find something to eat during prayer time to no avail. The film abruptly ends with the sound of the call to prayer and a credit sequence that stopped every time the prayer was recited. Needless to say, poking fun at religion this openly was not something one was used to seeing in the Gulf. It blew my mind to discover how these spunky young people basically didn't give a damn about what could very conceivably happen to them because of this daring attitude. 'Do you know what hell is? Well our life in Riyadh, it's a little worse than that,' I remember one of them telling me laughingly. It wasn't a surprise that much of their work was satirical because in such a heavily regulated environment comedy can present itself as a powerful weapon of choice. The audience will laugh and not take your statements at face value, so you can get away with integrating serious socio-political issues into the scenario and people will unsuspectingly embrace your message with open arms.

When his novel Shaghab (Riot, 2010) was banned by the authorities in late 2010 - first mainly for its title in light of the Arab uprisings at the time – writer Faisal Al-Amer teamed up with his animator friend Malek Nejer to create the satirical animated series called Masameer(Nails).[12] Faisal had just left his job writing for the local newspaper in Riyadh because of censorship problems, and Malek wanted to create a cartoon series that dealt with distinctly Saudi issues. Faisal incorporated sections of Shaghab into the episodes' script, which, when cloaked in cartoonish satirical garb, seemed harmless to the general populace watching it. 'We chose the Internet as the site to launch the series because it is a place where freedom runs wild, the censor sleeps, and this nagging question was dangling in front of our eyes: when was the last time any of us sat in front of a TV set?' The two worked tirelessly for months on this entirely self-funded operation, until they had exhausted themselves to a point that they felt that 'an elephant was peeling the skin off of our skulls', Al-Amer fondly describes. After their first episode was uploaded online, they were instantly showered with a wave of reactions from the public – both positive and negative – and the series became an overnight sensation.

I remember one of those early episodes entitled Animal (2012) which really read more like a philosophical manifesto than a funny cartoon.[13] It was about the hubris of humanity in relation to the natural world, and even referenced Darwin's theory of evolution, which should have raised a few eyebrows within such a rigidly religious community, but the colourful animated characters perfectly masked these politically incorrect concepts. Royalty, bureaucracy, corruption, boredom, drugs, religious zeal, geopolitical conflicts, cronyism and elitism are but a few of the radical topics Masameer has touched upon over the years. Today Masameer has millions of fans and viewers across the country and beyond, and the two have since co-founded a production company called Myrkott, which is housed in a large building in central Riyadh.[14] The cartoon also boasts many corporate sponsors, so it is in fact a businessin every sense of the word.

And this is an important point to consider when speaking of cultural initiatives and institutionalization of the arts in Saudi Arabia. If one is not a member of the royal family, or has no governmental blessing to create an arts initiative per se, or wants to actively remain outside the official authority's sphere of influence, how does one go about creating a grass-roots independent institution? Does the framework of a physical four-walled space with staff and a program apply in this environment, or does one have to become more imaginative and flexible, honing the skills to shift and bend whenever deemed necessary? Can the definition of institution be stretched to the point of just being perceived as a group of like-minded individuals who communicate their ideas either publicly or privately using any means available to them?

Here, one can imagine that there are two quick solutions at hand: either keep your activities forever concealed in underground circles or establish a corporation. Indeed, within the hyper-capitalist environment that the Gulf is founded on, 'going corporate' seems like the logical outcome of any successful project, artistic or otherwise. Corporatism and the private sector are one of the 'freest' domains one can occupy publicly, without being subjugated to endless red tape by officialdom. Running a business is less risky and more openly accepted than trying to open and run an independent art space. So Faisal and Malek's decision to create a company out of their initiative is not an uncommon occurrence, and one has to consider these creative 'companies' as institutional attempts in their own right.

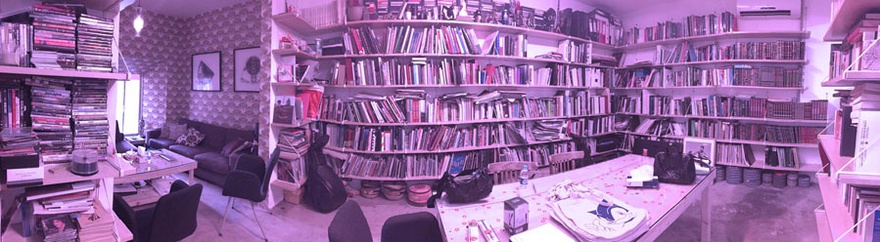

However, some persevere both outside the corporate and government realms and succeed at plugging the cultural vacuum they face. In the cosmopolitan seaside city of Jeddah, artists Ahmed Mater[15] and Arwa Al-Neami[16] have transformed their studio into a semi-public space, albeit somewhat unofficially. Inside, there are editing studios, a presentation room, a library, a common space, and plans for a residency space in the works. Artists, filmmakers, writers, and students congregate there to discuss their ideas and create new work, or just sit down to watch a film or read a book for inspiration. Pharan Studios, as it is called, is an earnest attempt to create the closest framework resembling an independent arts institution in Saudi Arabia. Anyone who knows the studio is welcome to enter it and its doors are open to friends and colleagues most of the time. While spending time at the studio, I felt electrified by the energy and thirst of the artists I met there. Needless to say, this buzzing atmosphere of discussion and exchange felt very different to what was happening in the rest of the Gulf. The 'wave' was very much palpable. People began coming out of the woodwork and making themselves known to each other and it was refreshing to just observe their interactions. Ahmed Mater himself is one of the leading contemporary artists in the country, who also openly critiques the status quo,[17] mainly pointing his finger at the violent urban destruction and renovation of Mecca itself.[18]

While in Jeddah, I also visited the house of a local designer, in the centre of which lay a huge empty swimming pool. This swimming pool – believe it or not – became the site of private film screenings, poetry recitations and stand-up comedy for many of the first generation experiencing the new wave. 'I did my first comedy show in here,' Hisham Fageeh told me,[19] who is now a bona-fide celebrity comedian and actor in the country. The pool isn't being used for these activities anymore, but I instinctively understood that the Jeddah arts community were having many rich and varied cultural experiences behind closed doors.

However, Saudi Arabia covers a huge geographic mass, and the story differs from place to place. Jeddah is in fact Saudi Arabia's most liberal city, mainly because the influx of pilgrims to Mecca over the centuries who have traditionally passed through it. It is multi-ethnic and multi-cultural, religiously more lax and open than other cities, and seems to be poised to become the centre of much of the Saudi arts scene's activities in the future. The official capital that is Riyadh presents a completely different landscape. With the frightening spaceship-like Ministry of Interior building towering over the cars passing underneath it in the centre of the city, the social and artistic sphere here felt much more constricted and desperate than Jeddah.[20] First of all, I didn't see many people walking around in public. They were either inside their cars, or in their homes, but rarely outside. Public space – even including restaurants and some shops – is strictly segregated and city-dwellers exist freely only in enclosed, isolated spaces. In one strange moment while I was observing it, I had a hallucinatory vision that the entire city was like one giant nuclear bunker and that all life here only occurred underneath the thick asphalt on the street.

Here, I encountered my true Samizdat experience, when I was lucky enough to meet a secret society of artists, musicians and writers. A Riyadh-based filmmaker colleague of mine from the old Dubai film circuit told me to come and meet his 'friends', who had created an underground society to discuss their ideas and work openly with each other. Membership was strictly controlled and I would be the first woman to enter their meeting space. But I had to conform to one condition: disguise myself as a man to access the bachelors-only building where that gathering took place. I put on my men's gallabiya in the car, and my friend proceeded to instruct me as follows:

Walk up to the building by yourself. Take the first right, then a left, then head straight until the end of the corridor. You will see a door with the number 'X' on it, it will be open. Just push it and enter. Hurry, you are a witness now.

And it really did feel like I was witnessing something significant. Despite the mountain of restrictions weighing down on them, young Saudis are finding creative and elusive ways to express themselves collaboratively and it is only a matter of time before these activities will no longer be restricted to back-door gatherings in the dark.

But regrettably for the meantime, the crackdown continues, and people are not always so lucky so as to not be caught in the act of articulating themselves candidly.[21] After the police stormed Talashi's studios in 2011 and arrested one of their members, the group has mostly moved to North America, and many of them do not plan on returning to Saudi Arabia. They have since significantly slowed their activities as a group. Ashraf Fayadh,[22] a poet, artist and curator from Abha in the southern region of the country, was randomly blamed for apostasy in 2013 after the authorities decided his book of poems Instructions Within – published five years prior to the incident – was heretic in nature. He is currently serving an eight-year jail sentence and has appealed his case. Raif Badawi,[23] a young writer and activist, was jailed in 2013 for founding the Free Saudi Liberals website, which allowed people to openly discuss sensitive topics, such as the role of religion in society and secular thought. He is currently serving a ten-year prison sentence with no chance of appeal.

So the reality of being Saudi and attempting to break the norms is still very much an extremely risky venture. Just as Bukovsky said of the Soviet underground 'I publish it myself; I spend jail time for it myself,' it is also an anticipated result of these defiant actions. But from what I have seen and heard in Saudi Arabia, the defiant forward-looking attitude is prevalent wherever you look despite the very real dangers and setbacks at hand. There is also a general sense of malaise – a 'no future' mental state, in that the youth don't feel like they have anything to lose anymore by exposing themselves out in the open.

I feel as outside observers, we must express our solidarity with this new movement in Saudi Arabia and look forward to what future it will bear. In my view, these grass-roots changes will eventually snowball into manifesting serious future institutions, albeit perhaps not in the traditional sense of four-walled buildings, but perhaps something more fluid, flexible and elusive. The Internet has created a parallel 'breathing space' to the extreme conservative ways of being Saudi in the world - and now the parallel space is definitely overtaking the old order.

Monira Al Qadiri is a Kuwaiti visual artist and film maker born in Senegal and educated in Japan. In 2010, she received a Ph.D. in inter-media art from Tokyo University of the Arts, where her research was focused on the aesthetics of sadness in the Middle-East region stemming from poetry, music, art and religious practices. Her practice explores the relationship between narcissism and masculinity, and is recently expanding towards more socio-political subjects. Al Qadiri has taken part in exhibitions and film screenings in Tokyo, Kuwait, Beirut, Dubai, Berlin, New York and Moscow among others. She is also part of the artist collective GCC.

[1] Mona Kareem, 'Why do you hate Khalijis?' Al Akhbar English, 29 August 2012, http://english.al-akhbar.com/print/11576

[2] 'Saudi Arabia grooves to new beat as entertainment sector opens up,' Gulf News, 7 October 2016, http://gulfnews.com/news/gulf/saudi-arabia/saudi-arabia-grooves-to-new-beat-as-entertainment-sector-opens-up-1.1908540

[3] Dennis Ross, 'In Saudi Arabia, a revolution disguised as reform,' The Washington Post, 8 September 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/global-opinions/in-saudi-arabia-a-revolution-disguised-as-reform/2016/09/08/979f03f6-7526-11e6-b786-19d0cb1ed06c_story.html

[4] Maya Jaggi, 'Is the Arab world ready for a reading revolution?' The Guardian, 16 April 2010, https://www.theguardian.com/books/booksblog/2010/apr/16/arab-world-reading-revolution

[5] M Lynx Qualey, 'The ‘Tyranny of Sex’ in the Saudi Novel,' Arabic Literature in English blog, 10 May 2010, https://arablit.org/2010/05/10/the-tyranny-of-sex-in-the-saudi-novel/

[6] M Lynx Qualey, ‘Revolutionary’ Chick Lit, Erotic Theology, and the Future of the Saudi Novel,' Arabic Literature in English blog, 9 May 2011, https://arablit.org/2011/05/09/revolutionary-chick-lit-erotic-theology-and-the-future-of-the-saudi-novel/

[7] Jasmine Bager, 'The Clandestine Adventures of Alice in Saudi Land,' Narratively, 1 October 2016, http://narrative.ly/the-clandestine-adventures-of-alice-in-saudi-land/

[8] Sholto Byrnes, 'Abdo Khal's Throwing Sparks stirs a paradise of horrors in Jeddah,' The National, 30 November 2012, http://www.thenational.ae/arts-culture/books/abdo-khals-throwing-sparks-stirs-a-paradise-of-horrors-in-jeddah#page2

[9] David E Miller, 'Saudi literary clubs told to do business by the book,' The Jerusalem Post, 5 December 2011, http://www.jpost.com/Middle-East/Saudi-literary-clubs-told-to-do-business-by-the-book

[10] 'Saudis waste eight hours daily on the internet,' Rev 2, 2014, http://www.rev2.org/2015/01/02/saudis-waste-eight-hours-daily-on-the-internet/

[11] Faiza Saleh Ambah, 'Aspiring Saudi Filmmakers Challenge Kingdom's Strict Mores, Movie Theater Ban,' The Washington Post, 15 January 2009, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/01/14/AR2009011404314.html

[17] Ahmed Mater, 'Singing Without Music,' ArtAsiaPacific, May/June 2015, http://artasiapacific.com/Magazine/93/SingingWithoutMusic

[18] 'Behind the hajj: Ahmed Mater's photographs of a Mecca in flux,' The Guardian, 14 September 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/cities/gallery/2016/sep/14/behind-hajj-photographs-mecca-flux-ahmed-mater

[21] 'Saudi Arabia amending laws to monitor social media,' Al Arabiya English, 2 June 2014,http://english.alarabiya.net/en/media/digital/2014/06/02/Saudi-Arabia-amending-laws-to-monitor-social-media.html

[22] David Batty and Mona Mahmoud, 'Palestinian poet Ashraf Fayadh's death sentence quashed by Saudi court,' The Guardian, 2 February 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/feb/02/palestinian-poet-ashraf-fayadhs-death-sentence-overturned-by-saudi-court