Reviews

Mass Individualism: A Form of Multitude

At Ab Anbar Gallery

Mass Individualism: A Form of Multitude, brought together nine artists of Iranian origin at Tehran's Ab Anbar gallery, in a show that began and ended in text. In her catalogue introduction, architect and curator Azadeh Zaferani framed the exhibition, which included Siah Armajani, Shahab Fotouhi, Babak Golkar, Shirazeh Houshiary, Y.Z Kami, Avish Khebrehzadeh, Arash Mozafari, Timo Nasseri and Newsha Tavakolian, through the Hellenic polis: a public sphere where conflict was mediated through the art of politics, or collective decision-making. Zaferani contrasted this ideal with the context of Iran, a country where the tension between public and private remains ever fraught and a disenfranchized contemporary society has become characterized by an increasingly polarized, atomized private realm.

The exhibition was broken up into four parts: public, action and speech; mass ornamentalism; technological revolution; and interior urbanism. Its most prominent theoretical touchstone was Rem Koolhaas' Ballardian series Exodus, or the voluntary prisoners of architecture (1972), which took Cold War West Berlin – a walled prison-as-refuge on the scale of the city, entered consentually – as a model for the dystopian metropolises of tomorrow. (A further assist was provided by the catalogue, which pulled in writings as disparate as T.S. Eliot's Burnt Norton, 1936; Adolf Loos' 'The Poor Little Rich Man', 1900; Svetlana Alexievich's Voices from Chernobyl, 1997; and Nima Yooshij's WWII lament Oh, Humans.) But if Koolhaas provided the show's conceptual scaffolding – a trio from Shirazeh Houshiary's Presence series (V, VI and VII; all 2012) felt like a Rorschach test for the same – then Babak Golkar's Loos Shelf (2015) served as a foundation. The ground-level installation collapsed the three floors of Adolf Loos' modernist landmark, Prague's Villa Müller, into a single integrated plan, which was then refashioned as a plywood structure that resembled a bookshelf. Exterior elements (walls) became an interior design feature, used to hold a selection of books like OMA's S, M, L, XL (1995); Ai Weiwei's Spatial Matters (2013); and issues of MONU magazine – texts that reflect the exhibition's curatorial interrogation of space and the knowledge it contains.

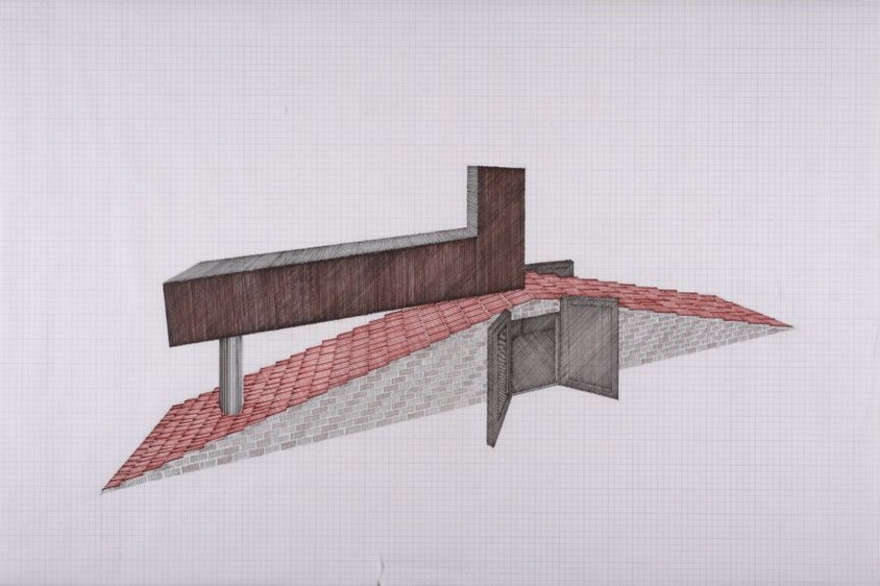

At the spatial and emotional heart of this multi-floor exhibition was Siah Armajani's Tomb for Neema (2014), an unassuming felt pen on graph paper sketch depicting a Tetris block of a casket affixed on a gabled, shingled roof. Part of a series in which Armajani imagines tombs for the 25 writers and activists who have most influenced his practice, the drawing paid tribute to Nima Yooshij, the contemporary Iranian poet who was instrumental in shifting poetic discourse away from the courtly realm into the public. Yooshij's rebellion was picked up in Avish Khebrehzadeh's animation (accompanied by spare drawings that feel more like stills), Edgar and Theatre III (2010). The work was tightly projected against the screen in a full-wall painting of an opulent, painted theatre, all gothic dusky blues and velvet seats, and featured a segued series of mildly absurd, symbolically loaded set pieces: palanquin bearers, a caged bird, a man digging himself into the ground, a circus strongman in high-waisted knickers with an assortment of animals, a one-legged man on crutches, and some balloons. The theatre was bereft of its audience and the figures had no mouths, any potential speech acts already foreclosed. The curtain fell with a lovely moment of deterritorialization, as the cage is knocked over and the bird slowly circles the theatre, multiplying into many and exceeding the frame.

But despite the release in Armajani's work, there was no escaping the tomb elsewhere in this exhibition. Shahab Fotouhi and Arash Mozafari's Untitled (2008) nodded towards how cities plan not only for the living but also for the dead. Following the catastrophic 2003 Bam earthquake, Iran commissioned a team of Japanese experts to assess the consequences of a similar seismic disaster in Tehran and to consult on emergency strategies. Their research found that although the initial fatalities would be around 10 per cent of the city's population, the risk of disease would bring the death toll much higher if preventative measure were not taken to dispose of the dead bodies. The municipality put out an open design call for proposed crematoriums (this was where the narrative blurred into design fiction territory; it was all unclear) stressing that, given its massive size, the structure should not impact the Tehrani skyline or its denizen's perceptions of business-as-usual.

Fotouhi and Mozafari's resulting installation drew upon the architectural tradition of muqarnas, or honeycombed ornamental vaulting to produce a glassily delicate structure topped with tetrahedral windmills whose painted birds and flowers further allude to an ascension to heaven. Yet if their parametric structure inverted the muqarnas, Timo Nasseri's Glance No. 10 (2010) turned it inside out with a spiky, ornamental mirror sculpture that broke and atomized the viewer's reflection. In the same room, an extruded sculpture from Babak Golkar's Parergon series (2011–2012) provided a further nod towards monumentality and the way in which architecture can become a tomb not only for bodies, but also for ideology itself. Like Khebrehzadeh's vacant theatre, the interrupted frame was decorative but emptied of both image and audience; its cut threw out a particularly beautiful shadow of Istanbul's Hagia Sophia.

A final literalized tomb was found in Y.Z. Kami's 12 oil portraits of unnamed, untitled men, each wearing a white crewneck t-shirt and imprisoned in a brick wall. They were reminiscent of the Fayum style of Egypt's Coptic period, in which images of the deceased were painted onto board and attached to the mummy. Yet there was none of the arrestingly direct connection associated with the Fayum tradition; the men in Kami's portraits seem to look past you. The brick here was ersatz – a digital print on irregular, scattered blocks – and the scale small enough that the effort of each brushstroke became vehemently visible. (If this was an incarceration, it was one that felt safely ensconced behind plate glass.) Outside, in an alleyway that leads to the gallery's entrance, in a tiny window-as-gallery itself trapped in a brick wall, was one last Y.Z Kami portrait, Untitled (Mr. Howard, 2001), It was hard not to notice Mr. Howard's darker skin, unlike the assorted sallow beiges presented inside the main gallery space. Perhaps not every prisoner of architecture is a voluntary one.

Mass Individualism was on show at the Ab Anbar Gallery, Tehran, from 15 April 2016 to 27 May 2016.