Reviews

Sketchat: Min Hone Wah Honak

The Sketches of Mahmoud Al Rifai at FADA 317

Situated in one of Amman's most popular areas, the FADA 317 art gallery in the Jabal Amman neighbourhood is oddly hard to find.[1] Founded in 2014 by cartoonist, illustrator, 3D model craftsman, and pioneer of Jordan's rapidly expanding graffiti scene, Mike V. Derderian, (or 'Sardine' as he is known in graffiti circles), FADA 317 is an attempt at engendering new forms of artistic appreciation by bringing attention to artists often overlooked by mainstream Jordanian art circles. Camouflaged between dusty, white-brick buildings and lacking any exterior sign, it can be found by way of Derderian's 'Anna Cosmonauta' character – a graffito of a woman's head wearing a space helmet – painted on the garage next to the gallery alongside an arrow pointing to the entrance. Inside the gallery space, one finds a main room for showcasing special exhibits and connecting rooms with permanent collections of Derderian's own works.

At the time of my visit, the gallery's main space presented 22 pen and watercolour sketches, some part-edited using Photoshop, representing various Amman locales and European cities by Jordanian artist Mahmoud Al Rifai in an exhibition titled Min Hone Wah Honak (in Arabic meaning 'From Here and There').[2] Most of the sketches were drawn with significant colour and detail, while a smaller number had been kept in their original black and white form or had limited colour added. One wall showcased six portraits that moved between black and white works focusing solely on people and coloured sketches that placed the subject into a larger spatial context. Another wall had two still life pieces, one of a motorcycle and another of a wooden carriage. (Anyone who has visited Jafra, the popular restaurant in downtown Amman whose theme evokes nostalgia for the heyday of Pan-Arabism, would recognize the carriage as part of its exterior decoration.) The remaining wall hosted the largest collection – a total of 14 sketches with seven each focusing on Jordanian and European architecture and public space

At the outset, it was difficult to discern the intention behind combining images of European cities with those of Amman, and no informational material explaining the decision accompanied the art. In some cases, European sketches were paired together. In other instances, there were pairings of sketches from Amman and Europe, which invited the audience to contemplate these images in relation to one another. The artist's European works focused primarily on well-known architectural landmarks such as the Acropolis, the Colosseum of Rome, and Venetian canals. Missing from these images, however, were the usual crowds of tourists eager to photograph and explore the sites. In their absence, the scenes evoked a tranquil setting that abstracted these historic monuments from their lived contexts. At first, it appeared as though the artist was simply highlighting the monumentality of key sites he visited during his travels throughout Europe.

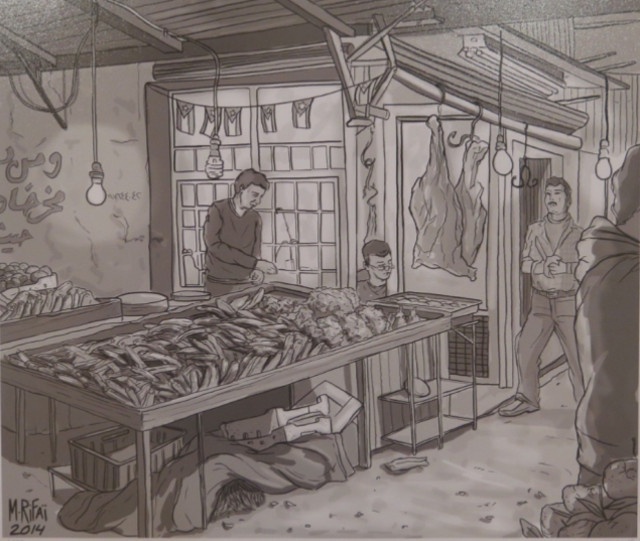

This initial reading was altered when gazing on a particular sketch of Amman's Roman citadel, which bore a resemblance to Al Rifai's drawings of Europe. The citadel is one of Amman's most well known and visible monuments, so its alignment with the European sketches served as an emphasis on the heritage signified by historic sites. Yet, for the most part, the sketches that focused on Amman's urban context were more concerned with the everyday street scenes and social dynamisms that characterize the lived experiences of the city's residents. For example, in contrast to the depictions of European cities, a number of Jordanian images were populated, giving viewers the sense that they were watching social life unfold. In one such work, Al Rifai depicted one of Amman's downtown markets (suq or aswaaq) where a fruit vendor organizes his products as he waits alongside neighbouring vendors for potential customers. The piece relates the viewer to activities rather than static architectural presence, and thus incites participation rather than spectatorship.

But it is not simply the presence of people in Al Rifai's Jordanian works that give them a particular richness; it is also his clear concern for detail and intimate understanding for the intricacies of urban Jordan that imbue these works with a sense of complexity. In the case of three images in the exhibition that focused on the architecture of central and east Amman, one of the most striking sketches depicts no people at all, but rather an apartment complex on Jabal Al Nadiefin east Amman – a building with partially-built walls that are slowly crumbling brick by brick and a steel wire skeleton that pokes out of the top. The complex is a common one in the area. It was clearly built as a functional rather than aesthetic space, and seems to be barely holding together. Although no people are depicted, the artist pulls the viewer's attention to numerous appropriations of the space such as laundry hanging from a window and graffiti on the exterior of the building. The focus here is on the material signs of urban life, which invites audiences to contemplate the ongoing biographies of the people and places that constitute east Amman.

Contrary to the dominant representations of Europe present in Al Rifai's other pieces, most of the sketches of Amman avoid the two common configurations with which the city is typically framed. The first configuration is the image of Amman as a successful embodiment of modern tastes, as exemplified by the new mixed-use Boulevard complex in the Abdali neighbourhood (also referred to as 'New Downtown'), which caters to local and international elites with upscale restaurants, boutiques, and apartments.[3] The second is the branding of the capital as the caretaker of civilizational heritage, exemplified by the Roman ruins that it was originally built around. These frameworks are connected to the significant alterations in Jordan's urban topography as the country has undergone neoliberal economic reform, in particular the five-star hotels, shopping malls and gated communities being constructed in the western part of the city. In response to this, Al Rifai places a special focus on the areas that have been left out of the city's development in his studies. By focusing some of his exhibition on the overlooked sites of central and east Amman, the artist thus offers a critical view on the wider context of society and the political economy of the country – a nod to the opposition between east Amman's working class struggle and the comforts of modernity in west Amman.

What does this narrative of Amman mean for the exhibition, which combines sketches of European and Jordanian spaces? It is possible that this choice could be interpreted as a reification of an 'East/West' binarism whereby Europe is framed as a model of development that Jordan should aspire to. This, of course, is the logic guiding much of the dominant representations and uneven development of Amman. However, Al Rifai challenges this logic by asking his audiences to consider areas of the city that working class Jordanians are animating everyday, outside of the dominate framework of development and modernization. In this insightful perspective on the complexity of 'the urban' in Amman, Al Rifai makes legible the forgotten, diverse sites and experiences of the city in ways that invites contemplation, nuance and presence. If nothing else, it allows for the visibility of spaces either rarely viewed, or actively obscured.

The Sketchat: Min Hone Wah Honak exhibition was on display at FADA 317 from 16 July to 17 August 2016.

[3] Promotional material for the Boulevard complex states, 'the Boulevard will compliment Abdali's vision in redefining modern living in the Jordanian capital by blending business, pleasure and contemporary urban lifestyles in one prestigious address, enhancing the capital's touristic and economic offering'. See: http://www.abdali-boulevard.jo/site/about