Essays

The Geopolitics of Contemporary Art

The discourse on the geopolitics of contemporary art is caught within two conflicting paradigms: an emerging view that stresses the open system of global flows, and the residual framework that is derived from the bounded territories of national structures. We seek to challenge these binary options by proposing a view from the 'South'. 'From', and not so much 'in', 'of' or 'here', is a key term today to rearticulate these polarities, and other related ones such as local/international, contextual/global, centre/peripheries, 'West/non-West'.[1]

The idea of the South is often rejected because it is perceived as merely inverting, and thereby reaffirming, the hegemonic geopolitics of the 'North'. It is undisputable that the common thread among those who identify with the South is shared rejection of the Euro-American monopoly over culture and knowledge. However, this negative awareness also contains a demand for alternative perspective.[2] As the art historian Anthony Gardner argues, the meaning of the South is not confined to 'either the geographical mappings of the southern hemisphere, or the geo-economic contours of the Global South as a category of economic deprivation'.[3] The South is part of a wider cultural agenda to overcome the colonial legacies through a shared affinity in the tragedies of settler domination over indigenous societies and the subsequent invention of new hybrid forms of self-affirmation. This quest for a new vocabulary for self-representation has also produced new cartographies of alliances and coalitions. Hence, the South is adopted as both a site in which cultural categories are subject to vigorous contestation and a worldview that addresses the trajectory of cultural flows. It highlights the trajectories that are not confined to the bi-polar movements between centre and periphery, but proceed within the horizontal spheres of 'South-South' connections, and along multidirectional networks. This loose zone and these complex lines of connection suggest that the idea of the South is not a fixed geographic entity, but a 'murky' concept and an ambivalent zone that sharpens old relationships and provides passage through new frontiers.[4]

The broad aim of this essay is to provide an insight into some aspects of the function of art in a globalizing world. This is not to claim that art is now doing the work of politics but rather to see how art is a vital agent in the shaping of the public imaginary. We will address this problematic in three ways. It outlines the resistance to the politics of globalization in contemporary art; presents the construction of an alternative geography of the imagination; and reflects on art's capacity to be expressive of the widest possible sense of being in the world and of 'being-on-the-globe': a notion coextensive to that of Heidegger through which Manray Hsu has emphasized the effects of globalization.[5] A worldview from the South disputes the validity of the centre-periphery model, and connects the critical insights generated by the debates on decolonial aesthesis with the widest possible sphere of cosmopolitan thinking. In short, our intention is to explore the worlds that artists make when they make art from the South.

Is there a critique that is 'Within and Beyond Globalization'?

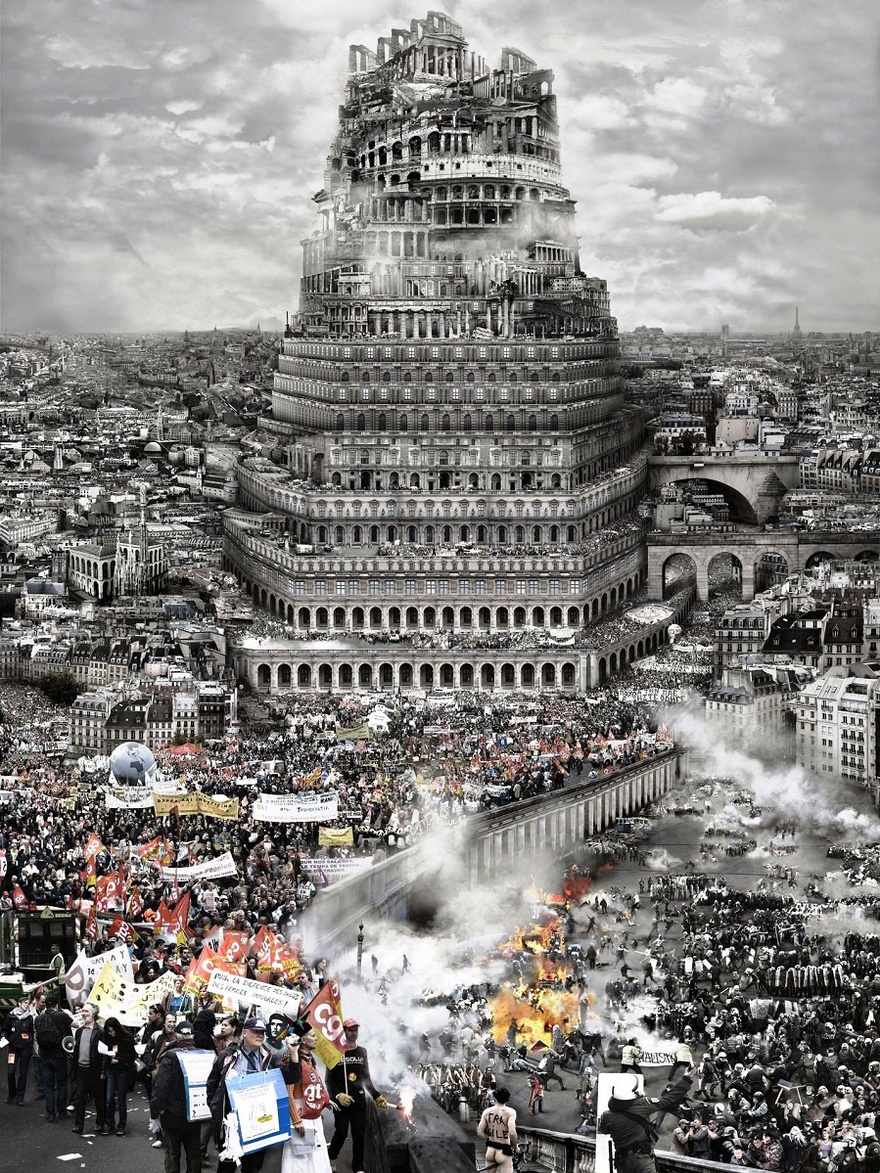

The emancipatory rhetoric of globalization has been overtaken by the grim realities of increasing geopolitical polarization, the precarious conditions of everyday life and a culture of ambient fear. In the broad sphere of contemporary art the discourse of globalization is often at odds with these conditions. It is not a simple matter of empty and deceptive global babble. There is undisputable evidence of a process of cosmopolitanization; the emergence of globalizing institutions; a proliferation of events that stage art within global frameworks; and the expansion in the creation of contemporary art to vast 'zones of silence'[6] in which it was not practiced before – a recognition that cultural vitality is dependent on exchange, unprecedented mobility in the biographies of artists and critics, and the emergence of scholarly and popular debates on the possibility that contemporary art is expressive of an interdependent world.

However, while some of the nineteenth-century Eurocentric barriers and racist hierarchies have been broken by these cosmopolitan tendencies and globalizing discourses, and although there is a proliferation of locations in which the contemporary art world operates, it is also a context that is marked by complex network of dispersed lines of power and distributed clusters of concentrated energy. The shape of the art world is a puzzle. It is neither flat and equal, nor stacked in a hierarchy that resembles a pyramid. Many people take comfort in marvelling at the diversity of places of origin among participating artists in major biennials. Yet, this appearance of a globalizing world is quickly punctured by another detail that now takes prominence in the way artists define their residence. For instance, over half of the artworks shown at Documenta 12 and the 2007 Venice Biennale were produced by artists that are designated as: 'based in Berlin'. Gregory Sholette quite rightly claims that the vast majority of the art world exists in a creative equivalent to what physicists call dark matter. That is, over 96 percent of all creative activity is rendered invisible in order to secure the ground and concentrate the resources that are necessary for making the privileged few hyper-visible.[7]

In this context of gross inequality and heavy concentration in the new focal points, it is necessary to develop a new approach towards the critical function of art. We argue that contemporary art occupies a complex topology: it is increasingly seeking to be a critique from within and beyond globalizaton. The radical aim is not to simply widen the aesthetic terms of entry and extend the art historical categories of reception, but to develop a polycentric perspective on the multitude of artistic practices, rethink the conceptual frameworks for addressing the interplay between art and politics, and open up the horizon for situating the flows between the perceptual faculties and the contextual domain. This shift in approach and thematic understanding is also driven by transformations in the conditions of artistic production, the logic of cultural participation, and the status of the image in contemporary society. The bulk of artistic practice now arises from a mixed economy of production. Many artists now work in a collective environment and adopt collaborative methodologies. Even artists who prefer to work alone in their studio are outsourcing more and more of the technical production of their artwork. At a time when art is being subsumed in brand culture, the hand of the artist is also becoming less and less visible.

The position of the public has also moved away from being passive receivers of information, and adopted a more active role as active co-producers and participants in the shaping of their own experience. The proliferation of images, the diversification of visual techniques, and the incorporation of visual images into communicative technologies also produced a phenomenon that we define as the 'ambient image'. In this context the image is not just a pervasive element in everyday life, but its function has come to dominate other communicative practices. There is now a blurring of the boundary between the image and other forms of conveying information and knowledge.

In 1996 the curator and critic Nicolas Bourriaud observed that artists had already developed sophisticated responses to the radical transformation of public space.[8] This transformation had been generated by the rise of informal networks and social entrepreneurship, as well as the contraction of state support for public institutions and civic spaces. Amidst these structural changes there has also emerged a new discourse on the function of creativity. Sociologists have taken a lead role in both promoting the innovations produced by cultural agents, and protesting against the precarious working conditions that are endemic to this 'lifestyle'.[9] The spread of this ambivalent perspective on creativity has also prompted a more nuanced awareness of the place of contemporary art in the capitalist network. Firstly, it has not only highlighted the polarizing and unequal distribution of rewards within the cultural sector, but it has also helped focus attention on the tendency to reduce the merit of artistic work to a narrow form of instrumental welfare benefit and immediate financial return. The instrumentalization of art has proceeded at pace with the growing rhetoric that – everyone is now creative.

Secondly, the dispersal of creativity into all aspects of everyday life also provides a conceptual challenge. In the early parts of the twentieth century the formation of a creative industry was linked to the technologies for the mass production and standardization of culture. The critical discourse that was developed by Theodor Adorno from the Frankfurt School tended to highlight the extent to which the public was repeatedly duped. In the current context, the technologies of cultural dissemination have become more dispersed and the complicity between producers and consumers is far more inter-connected. Hence, the role of the critic is no longer confined to performing the task of exposing the means for manipulation and the forms of deception. Critical thinking now requires more than showing how the public is the victim of false and distorted messages. This is not an entirely new step (think on Stuart Hall's 'encoding/decoding' discussions about TV, mass media, and the audience's active role in reception), but rather it is a move from ideological critique towards the genre that gives more space to the sensory experience of the interplay between the virtual and actual world. It is a genre that resembles the mode of writing that Taussig calls 'fabulation'[10] and Latour calls 'poetic writing'.[11]

Thirdly, recognizing that the public consumption of dominant cultural forms is not an automatic sign that the public imaginary is being totally controlled has provoked the need for a more nuanced view of the forms of cultural agency. More recently, Gerald Raunig has argued that it is necessary to unpack the links between the dominant forms of cultural production and the processes of cultural participation.[12] The conceptual frame that is proposed by Raunig addresses a cultural dynamic that is formed by the double functionality of forces that produces both a disconnection between positions that are inside, and a feedback towards those that are outside the system. From this perspective, it is possible to conceptualize the relationship between art and politics in terms that exceed the conventional and oppositional binaries. This framework is also compatible with subaltern perspectives and what we propose as the view from the South.

By reconfiguring the relationships in the production of art, this discourse has also dislodged one of the key barriers that confined artistic production in the South to either the category of the static folklore, or the ghetto of the local community. There is now an opportunity to situate the South as part of the contemporary debates of global culture. However, even with these new conceptual advances the road ahead is filled with risks and contradictions. For the view of the South to make a difference we need to have a zone that is beyond globalization.

In addressing the tension between the globalizing trajectories and a cosmopolitan worldview, we will – for now – take the lead offered by Jan Nederveen Pieterse in his identification of the problems that are endemic in global thinking.[13] Pieterse notes that while theories of globalization have developed a wide range of sophistication and breadth, there is the inherent problem of constructing a perspective that relies on aggregation and generalization. The attempt to produce an overview by squeezing diverse groups into a broad category; the need to arrive at a common sum by adding together all participants; the drive to produce a shared identity at expense of stripping everything back to an essentialist schema; the search to find a representative who can speak on behalf of others; the problem of creating an image by objectifying all the living elements; and the belief that progress begins at an agreed point and continues along straight lines: these are features that mar the possibility of a genuine mode of global thinking. If global thinking is embedded in such a conceptual dynamic of aggregation and generalization, then the local will always be subordinate to the same structures that organized the colonial imaginary. The 'global' will thus be made for a 'local' that has been stripped of agency. In short, within this globalizing framework the view from the South will struggle to challenge the mindset that dominated the colonial world. The idea of the South cannot proceed as just a subset of this vision of globalization. It will require a new vocabulary and apparatus, and of course, it is easier to demand new tools than it is to make them.

The Geography of the Imagination

The freedom of the imagination is not in opposition to the understanding that it begins from a fixed location. It can be used to reflect back the view of a reality that awaits just around the corner, to generate a vision of another reality that is based on elements that already exist in the here and now, as well as to split the singular conception of reality into a multitude. This perspective contains a dialogic relationship between global forces and local experiences. We adopt this approach because we believe that there is a significant conjunction between artistic practice, curatorial strategies and theoretical investigations. In all these spheres of critical thinking and imaginative speculation there is a consistent effort to both de-provincialize the imagination and develop a wider conceptual framework.

The breadth of vision and the attention to the (often brutal) edges of local encounters can be found in the examples of artistic practices in India, south-east Asia and Latin America that are discussed by Cuauhtémoc Medina, Weng Choy Lee and Ranjit Hoskote. It is not a coincidence that these writers are simultaneously theorists of contemporary culture and curators who have been engaged in the region of the South. They have all observed the way that artists now literally throw themselves into extreme conditions, assume the role of mediators in complex cultural cross-roads, give form to nebulous threshold experiences and create situations in which the imagination can take each participant into an unknown world. Between these worlds there are the heavy extremities of unfulfilled hopes and the realization of apocalyptic fears.

According to Cuauhtémoc Medina, a curator and writer working in Mexico, the consequences of globalization have not led to the refinement of a cosmopolitan subjectivity – so that the peoples of the world are more sensitive towards each other's needs and appreciative of their cultural difference – but on the contrary, it has produced a heightened exposure to physical violence, economic instability and the disruption of social norms. Medina's curatorial practice is studded with examples of artists that have a habit of both putting their finger into the wound, and creating a more direct cartography of interconnection between the global and the local.[14] Ranjit Hoskote also explores the dialogue between local artistic practices and the wider discourses that are circulating in a global arena. He asserts that, despite the negative connotations of belatedness, the periphery is often a far more dynamic theatre of development than the centre. As Hoskote argues, artists do not confine their imagination to their place of origin, and in order to capture the meld of the local and the global that constitutes the 'armature of place across our planet' he opts for a perspective that highlights the critical transregionality of flows in the Indian sub-continent.'[15]

Such a perspective does not simply extend the nationalist category of belonging by stretching the borders or updating the names of constituents. It is a viewpoint that challenges the foundational ideas of exclusive territorial attachments. To re-imagine the sense of artistic belonging in terms of critical transregionality is a step away from the Enlightenment and Eurocentric traditions of national consciousness and move towards a more creative affiliation to place. This motion also involves a sensate connection to a more generalized notion of the public, or what Mieke Bal has defined as a more pervasive form of the 'migratory aesthetic'.[16] Bal stresses that art can stimulate both a conceptual staging of movement and the affect of being moved. Through the production of structures and zones of encounters art becomes a new kind of medium or vessel that Bal elegantly terms as 'inter-ship'.[17] The experience of this 'migration aesthetic' is therefore not just a movement from a given place, but also a deeper sense of binding with the apprehension of the common in a public space. It lets our imagination connect to other places and also confronts the need to make a public space.

A vital step in de-provincializing the imagination thus begins in the confrontation with the limits of Eurocentric universalism. This was a challenge that was most powerfully articulated by the Subaltern Studies group in India. While Lee Weng Choy has noted that the South tends to lack a 'discursive density' to sustain a comprehensive platform for wider public engagement, he also noted that the contradictions in western claims to globality are most clearly perceived and forcefully countered from this position.[18] These debates on the limits of western conceptions of world culture have been raging for at least three decades. Throughout this period, critics and scholars responded by experimenting with new theoretical frameworks that could address the hybrid and diasporic cultural formations. Evidence of these new approaches can be found in the fabulous archives of journals such as Third Text (London), Thesis 11 (Melbourne), Revista de Crítica Cultural (Santiago, Chile), Public Culture (Chicago) and South as a State of Mind (Athens). The impact of these debates was profound.

The leading scholars and journals in the metropolitan capitals of the art world were desperate to demonstrate that their outlook was not constrained by any provincial biases or blinkers. For instance, in a recent article for Artforum the American art historian David Joselit asks: 'What is the proper unit of measurement in exhibiting the history of a global art world?'[19] Joselit notes that the nation is still the fallback framework for explaining the historical context of art. However, he rejects the view that the locus of art's belonging is confined to territorial boundaries. He proposes an alternative dual perspective. First, he focuses on the biography of artists. He astutely notes that artists are forever 'shuttling between their place of origin and various metropolitan centres while participating throughout the world'.[20] He also aims to reinvigorate the avant-garde idea of an artistic movement as an organizing principle for contemporary art. This idea is promoted because it combines the unifying process of putting forth a distinctive philosophical concept or aesthetic style, with the physical mobility of people and ideas within a network. Hence, Joselit proposes that contemporary art can be mapped in relation to the various movements that have been assembled in a given place and succeeded each other over time.

Similarly, the influential American theorist and art historian James Elkins has claimed that the western conceptual footings of art history can be extended to cover the global production of art.[21] He also has insisted that the field upon which such shared methods, concepts and premises are established are existing western categories. Weng Choy points out that such an endeavour can only succeed to bring into view a portion of the world that is already familiar with and consistent with its own 'instituted perspective'.[22] This is a disciplining exercise of the world of art, rather than an exploration of the phenomenon of contemporary art. Again, Weng Choy sees this paradoxical acknowledgement of diversity in cultural differences and a reinscription of the hegemonic viewpoint in the framework proposed by the editors of the art theory journal October. If one takes the view from the South seriously, it is hard to be convinced by the claim that while contemporary art is both set 'free of historical determination, conceptual definition and critical judgement', and at the same time even more bound to the objecthood of institutional apparatus.[23]

At the 11th Havana Biennial Universes in Universe (2012), a collective of artists, curators and writers called Decolonial AestheSis presented a series of panel discussions that sought to investigate the creative processes that are underway in the South from a triple negative perspective that is 'delinked' from the Eurocentric philosophical models, as well as distinct from either the nationalist and globalizing discourses.[24] This refreshing and ambitious agenda was based on the recognition that while colonization is more or less over in the South, the experience of coloniality is still endemic and a residual feature of critical thinking and creative practice. In short, while the structures that govern the geo-political context cannot be examined through a colonial prism, the concepts such as progress, development and innovation are still heavily shaped by a knowledge system that reflects the Eurocentric worldview. Thus 'denaming' and unveiling the hegemonic nexus between modernity and rationality were proposed as the crucial starting points in this collective endeavour to decolonize the imaginary.

This project drew on the 2011 argument (as manifesto for decolonial aesthetics) put forward by the Centre for Global Studies and the Humanities, at Duke University.[25] In this short but sweeping document the authors claim that two new concepts are necessary to address the radical change in the relationship between cultural production and geo-politics. First, they assert the idea of 'transnational identities-in-politics', which is an affirmation of identity in its multiple formations that has resisted the homogenizing forces of globalization. These identities are an embodiment of a pluriversalist worldview that articulates a sensory awareness of the world through the material and political engagement in the world. Second, they claim that decolonial aesthetics is a liberation of sensing and sensibilities from the territorial and instrumental paradigms of coloniality. It will encourage a ground-up mode of intercultural exchange and lead to the 're-inscribing, embodying and dignifying [of] those ways of living, thinking and sensing that were violently devalued and demonized by colonial, imperial and interventionist agendas as well as by postmodern and altermodern internal critiques'.

We acknowledge the profound steps taken by these collectives, and in order to sharpen the argument against the dominant construction of the 'units of belonging' proposed in the Eurocentric art historical discourses, we would contend that the unit of aesthetic belonging in the world is even bigger, more diffuse and paradoxically also more place-based than the sense of belonging that is conveyed by the notion of a trans-territorial unit. The trans-territorial conception of globality in the art world still retains a fundamental faith in art as a generator of 'newness'. The art world's attraction to the diasporic condition, an emergent cosmopolitan order and the challenge of globality, is repeatedly framed in an economy that translates the foreign into the familiar. This is the economy of metropolitan benefit, whereby the centre accumulates as the periphery donates. It is the same economy that reduces aesthetic practice to a machine that feeds the ever-hungry desire for novel forms of ornamentation and objects of instrumental value. This attitude towards art as a producer of different forms, new perspectives and more accurate representations of the world is a central element in the validation of modern culture. Hence, the dominant conception of modernism accentuates a specific idea of modern subjectivity. It retains the belief that artists have ability to see the world anew, and to create objects of value. However, much of the motivation that is driving the recent re-evaluation of modernism and the growing popularity of contemporary art is sustained by the underlying belief that artists are the source of an ever expanding supply of globally branded commodities and the trend setters for global fashion. The corollary to this is that the globalizing appetite for contemporary art is showing a scant regard for the way art provides a form of place-based knowledge.

We agree in part with the observations made by the editors of October – that there is an absence of a shared cultural framework for situating and defining the meaning of contemporary art. It is also evident that critical responses to contemporary art are, at best, provisional, partial and fragmented. The limits to these interpretative responses are, in part, determined by the near infinite range of cultural references that are embedded in the sphere of contemporary art. No critic can walk through any biennial and presume to know where all the artists are 'coming from' and to pronounce that he or she is able to 'get it' all! However, the conceptual problem is not confined to an ability to apprehend the diverse backgrounds and wide political agenda that are evoked in the content of the artwork. There is also the radical challenge of multiple perspectival and perceptual possibilities that are generated by immersive and screen-based artworks. In this predicament, even when the audience engages with the work of an artist, they are effectively responding to different feedback loops and triggering different sensors that produce discontinuous sequences of imagery. Hence, there is no fixed image or singular narrative to which the interpretation is directed. Everyone can enter the work of a single artist but no two people exit having seen the same artwork. The challenge of perceptual contingency and cultural incommensurability that this predicament summons cannot be resolved by either re-instating the pre-existing categories of art, or tightening the grip of the institutional apparatus. We propose that a new conceptual framework is necessary, one that embraces these shifts in perspective and the interplay between cultural differences. We argue that a different kind of worldliness is also in motion in the world of contemporary art. As Hans Belting has argued, there are so many worlds in the art world that it is now impossible as a curator to be a global surveyor.[26] Conversely, 'it is unlikely that there could be global art, in the sense of artworks that are recognized as such everywhere', as Charlotte Bydler has put it.[27] What do we do with this excess? Do we retreat into the orthodoxy of prior categories? Assume that the abundance of production will also carry forth a plurality of critical perspectives? Or, do we take a third position, one that departs from the dictates of universalism and relativism, and takes its cues from the challenges of the multiple encounters in the world.

Into Cosmos

Cosmopolitanism is another concept that is increasingly adopted to address a wide range of functions. It is being used to define the dynamics of cultural exchange between the local and the global, explain the agency of artists that are prominent in the global art world, and also serve as an overriding frame for the space of contemporary art. The curator Nicolas Bourriaud claims that contemporary artworks are invariably translating local and global forms.[28] Artists are seen as exemplars of a new global self.[29] Biennales and festivals are seen as platforms for bringing ideas from all over the world into a new critical and interactive framework.[30] These are contestable propositions. However, our concern is not to expose the gaps in the curatorial surveys, question the embodiment of a cosmopolitan subjectivity, or even dismiss global art events as a cultural smokescreen for corporate capitalism. Rather than pursuing a polemical engagement with the structural balance between global opportunities and deficits, we now seek to consider the geo-political context of contemporary art within the widest possible frame, what we call the cosmos of art.

Exploring the cosmos of art is not the same as the art historical surveys of the global art world. The ambitious surveys of artistic developments across the world, whether they are conducted by teams that are distributed across different regions,[31] or directed by a solitary figure who has sought to integrate emergent trajectories and classify diverse practices into a new hierarchy,[32] there is always the risk of repeating the conceptual problems of aggregation and generalization.[33] To have a total worldview of contemporary art is now impossible. Art is produced at such a rate and in so many different places that no one can ever see the whole. The events and horizons of contemporary art have become resistant to any totalizing schema. International critics and curators have to work today from the awareness of our ignorance. However, by bringing into closer focus the elemental terms of globe and cosmos we seek to develop an alternative exercise in imagining the aesthetic forms of connection and being in the world. A simple distinction may help. In the most banal uses of globalization there is very little significance given to the key term globe. The world is treated as a flat surface upon which everything is brought closer together and governed by a common set of rules. Globalization has an integrative dynamic, but a globe without a complex 'ecology of practices'[34] would not have a world. A world is more than a surface upon which human action occurs. Therefore the process of globalization is not simply the 'closing in' of distant forces and the 'coordination between' disparate elements that are dispersed across the territory of the world. As early as the 1950s Kostas Axelos made a distinction between the French term 'mondialization' and globalization. He defined mondialization as an open process of thought through which one becomes worldly.[35] He thereby distinguished between the empirical or material ways in which the world is integrated by technology from the conceptual and subjective process of understanding that is inextricably connected to the formation of a worldview. The etymology of cosmos also implies a world-making activity. In Homer the term cosmos is used to refer to an aesthetic act of creating order, as well as referring to the generative sphere of creation that exists between the earth and the boundless universe.

Cosmopolitanism is now commonly understood as an idea and an ideal for embracing the whole of the human community.[36] Everyone who is committed to it recalls the phrase first used by Socrates and then adopted as a motif by the Stoics: 'I am a citizen of the world'. Indeed the etymology of the word – as it is derived from cosmos and polites – is expressive of the tension between the part and the whole, aesthetics and politics. In both the Pre-Socratic and the Hellenistic schools of philosophy, this tension was related to cosmological explanations of the origin and structure of the universe. In these early creation stories the individual comes from the abyss of the void, looks up into the infinite cosmos and seeks to give form to their place in the world. It is also, in more prosaic terms, a concept for expressing the desire to be able to live with all the other people in this world. This ideal recurs in almost every civilization. In the absence of this ideal being materialized as a political institution, it nevertheless persists and reappears as a cultural construct in each epoch. This tension between the residual cosmopolitan imagination and the absent historical form of cosmopolitanism also appears to be a constant in the artistic imaginary. We claim that artistic expression is in part a symbolic gesture of belonging to the world. This wider claim about the perceptual and contextual horizon of art is drawn from the belief that it draws from ancient cosmological ideas and the modern normative cosmopolitan ideals.

For the Stoic philosophers in the Hellenistic era, the concept of cosmopolitanism was expressed in an inter-related manner – there was spiritual sense of belonging, and aesthetic affection for all things, as well as political rumination on the possibility of political equality and moral responsibility. Since the Stoics, the spiritual and aesthetic dimensions of cosmopolitanism have been truncated. By the time Kant adopted cosmopolitanism as a key concept for thinking about global peace, the focus was almost entirely on de-provincializing the political imaginary and extolling the moral benefits of extending a notion of equal worth to all human beings. Since Kant, the debates on cosmopolitanism have been even more tightly bound to the twin notions of moral obligations and the virtue of an open interest in others.

Cosmos, for our purpose, refers to the realm of imaginary possibilities and the systems by which we make sense of our place in the world. In recent debates on aesthetics and cosmopolitanism there has been close attention to themes such as spirit, heart, empathy, mystery, void, vortex, universe.[37] What sorts of worlds are made in the artistic imaginary? Can we grasp the cosmos of art if we confine our attention to the traditional methods of iconography and contextual interpretation? Is something else necessary? It is from this perspective – one that draws out the radical dimensions of empathy to include a connection to material and formal elements; the techne and physis of artistic production – that we seek to highlight the aesthetic dimensions of cosmopolitanism. In fact, we will claim that the dominant emphasis on the moral framework and the disregard for the aesthetic process has constrained the scope of being cosmopolitan. The expression of interest in others, or the willingness to recognize the worth of other cultures is no doubt a worthy moral stance, and a necessary stance if we are to engage in any dialogue about what is possible in a world in which rival viewpoints jostle for space. However, if this approach is defined exclusively in a moral framework, it also constrains the very possibility of being interested in others. In short, if interest in others is subsumed under the moral imperative of feeling obliged to respect others then the possibility of an aesthetic engagement is subordinate to a normative order.

But from where does the impulse of conviviality come? Let us take a few steps back to the idea that cosmos is an order-making activity. Cosmos is not just a counter to the condition of chaos, and an intermediary zone between the material earth and the boundless space of the universe, but is also the fundamental activity of making a space attractive for others. We suggest that a cosmos starts in the primal desire to make a world out of the torsion that comes from facing both the abyss of the void and the eternity of the universe. This act of facing is a big bang aesthetic moment, filled with the horror and delight. Our aesthetic interest in the cosmos is therefore interlinked with the social need for conviviality. The everyday acts of curiosity, attraction and play with others does not always come from a moral imperative, but also from aesthetic interest. Do we possess a language that can speak towards the mystery of this interest? Art history, and the humanities in general, have struggled to develop a language that is suitable for representing the mercurial energy of aesthetic creation. The pitfalls of the two extremes – between either narcissistic mystical illusionism or empirical instrumentalism – is most evident in the contrast between Romanticism and Marxism.

The aesthetic dimension of cosmopolitanism begins with the faculty of sensory perception and the process of imagination. We commence with the proposition that the act of the imagination is a means of creating images that express an interest in the world and others. Imagination is the means by which the act of facing the cosmos is given form. Imagination – irrespective of the dimensions of the resulting form – is a world picture-making process. Therefore, the appearance of cosmopolitan tendencies in contemporary art, are not just the cultural manifestations of globalization.

The ultimate aim of this introduction is to expand our understanding of art by reconfiguring the debates on the geo-politics of aesthetics and consider the extent to which the local and the global are constantly interpenetrating each other. There is a need for a new conceptual framework that speaks to this process, to unzip the conventional hierarchy between local and global, assert that place really matters in art, and re-think the scope of key concepts universalism and globalization.

Against these two terms we put forward the terms of pluriversalism and cosmopolitanism. Pluriversalism acknowledges both the diversity and co-existence of rival truth claims. However, rather than subordinating each of these different viewpoints into a pre-existing framework it also accepts that the participants in a cross-cultural dialogue will also have a hand in shaping the framework through which an over-arching meaning can be established. A pluriversalist approach admits cultural difference, but does not re-inscribe them within pre-determined western categories. It distributes a wider level of responsibility to all the participants in contemporary art. It is a critical methodology that not only acknowledges the empirical reality of globality in the art world, that is, the diverse contributions to contemporary global culture, but also seeks to develop a new theoretical approach to the relations between different cultural perspectives in this geo-political context. This approach is not only focused on the redistribution of agency in the production of meaning and event, but also concerned with tracing the participant's capacity to imagine their place in the world as a whole. It combines a critique of the 'rootlessness' of the cosmopolitan figure, while grounding the jagged forms of cosmopolitanism that are produced by the displaced and disenfranchised. It highlights the hybrid practices of artists as they translate local forms with the other forms found in the regional neighbourhood and global environment. It challenges the presumption of separation and exclusion by revitalizing ethics of hospitality through the aesthetic prism of curiosity, and finally it promotes a call for new social and political forms of collaboration in a global public sphere.

Cosmopolitanism is usually understood as both a descriptive term that refers to metropolitan situations in which cultural differences are increasingly entangled, and as a normative concept for representing a sense of moral belonging to the world as a whole. More recently, the concept of cosmopolitanism has been applied to the political networks formed through transnational social movements, and the emergent legal framework that extends political rights beyond exclusivist territorial boundaries. In its most comprehensive mode, the concept of cosmopolitanism also assumes a critical inflection whereby it refers to the process of self-transformation that occurs in the encounter with the other.

Cosmopolitanism thus captures a diverse range of critical discourses that address the shifts in perspectival awareness as a result of the global spheres of communication; the cultural transformation generated by new patterns of mobility; the emergence of transnational social networks and structures; and the processes of self transformation that are precipitated through the encounter with alterity. However, the normative discourse on global citizenship does seem rather lonely and out of touch. Our hope is that by addressing contemporary art within the conceptual frame of the cosmos we can also reinvigorate both the sensory awareness and a more worldly form of belonging.

This is a revised version of an introduction to a special issue on the Geopolitics of Contemporary Art edited by Gerardo Mosquera and Nikos Papastergiadis for the Visual Arts Magazine ERRATA # issue number 14. It seeks to analyse the relationships South to South – South America, South Asia, South Africa – responding to the hegemony of Eurocentrist and Anglo-Saxon tradition. It will be published in Colombia and the text will appear in Spanish.

[1] Gerardo Mosquera, Caminar con el Diablo: Textos sobre arte, internacionalización y culturas (Madrid: Exit Publicaciones, 2010).

[2] Gerardo Mosquera, 'Alien-Own/Own-Alien' in Complex Entanglements, Art, Globalization and Cultural Difference, ed. N. Papastergiadis (London: Rivers Oram Press, 2003), pp.19-29.

[3] Anthony Gardner, 'Biennales on the Edge, or, A View of Biennales from Southern Perspectives,' in Higher Atlas, The Marrakesh Biennale, eds. C. Chan and N. Samman (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2012), pp.88-123.

[4] Nikos Papastergiadis, 'What is the South?' in South, South, South, South, ed. Cuauhtemoc Medina (Mexico City: SITAC, 2010), pp.46 -64.

[5] Manray Hsu, 'Networked Cosmopolitanism: On Cultural Exchange and International Exhibition,' in Knowledge+Dialogue+Exchange. Remapping Cultural Globalisms from the South, ed. Nicholas Tsoutas (Sydney: Artspace Visual Arts Centre, 2004), p. 80.

[6] Gerardo Mosquera, 'Notes on Globalisation, Art and Cultural Difference,' in Silent Zones: On Globalisation and Cultural Interaction (Amsterdam: Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten, 2001), pp.26-62.

[7] Gregory Sholette, Dark Matter: Art and Politics in the Age of Enterprise Culture (London: Pluto Press, 2011), p. 3.

[8] Nicolas Bourriaud, 'An introduction to relational aesthetics,' in Traffic, ed. Nicolas Bouriaud (Bourdeaux: CAPC Musee d'art contemporain, 1996).

[9] Luc Boltanski & Ève Chiapello, The New Spirit of Capitalism, trans. G. Elliott (London: Verso, 2007).

[10] Michael Taussig, Shamanism, Colonialism and the Wild Man (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1986).

[11] Bruno Latour, 'Why Has Critique Run out of Steam? From Matters of Fact to Matters of Concern,' Critical Inquiry 30.2 (2004): pp.225-248.

[12] Gerald Raunig, Factories of Knowledge, trans. A. Derieg (Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2013).

[13] Jan Nederveen Pieterse, 'What is Globalization,' Globalizations 10.4 (2013).

[14] Carlos Medina, 'Seeing Red,' in Art in the Global Present, eds. N. Papastergiadis and V. Lynn (Sydney: UTS Press, 2014), pp.133-156.

[15] Ranjit Hoskote, 'Global Art and Lost Regional Histories,' in Art in the Global Present, eds. N. Papastergiadis and V. Lynn (Sydney: UTS Press, 2014), pp.186-192.

[16] Mieke Bal, 'Bunuel's Critique of Nationalism: A Migratory Aesthetic?' in A Companion to Luis Buñuel, eds. R. Stone and D. Gutierrez-Albila (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwells, 2013), pp.116-137.

[17] Mieke Bal,'Imagining Madness: Inter-ships' In/Print 2 (2013): pp.52-70.

[18] Lee Weng Choy, 'A Country of Last Whales – Contemplating the Horizon of Global Art History; Or, Can we Ever Really Understand How Big the World Is?' Third Text 25.4 (2011): pp.447-457.

[19] David Joselit, 'Categorical Measures' Artforum 51.4 (2013): p. 297.

[20] Ibid.

[21] James Elkins, 'Art History as a Global Discipline,' in Is Art Hisotry Global? (New York: Routledge, 2007), p. 3.

[22] Choy, op cit., p. 453.

[23] Rosalind Krauss et al., 'Questionnaire on "The Contemporary,"' October 130 (2009): pp.3-124.

[24] Raul Moarquech Ferrera-Balanquet and Miguel Rojas-Sotelo, 'Decolonial Aesthesis at the 11th Havana Biennial,' Social Text (2013): socialtextjournal.org/periscope_article/decolonial-aesthesis-at-the-11th-havana-biennial/.

[25] Walter Mignolo et al., 'The Argument (as manifesto for decolonial aesthetics),' The Center for Global Studies and the Humanities website https://globalstudies.trinity.duke.edu/the-argument-as-manifesto-for-decolonial-aesthetics.

[26] Hans Belting, 'Contemporary Art as Global Art: A Critical Estimate,' Global Art Museum website http://globalartmuseum.de/media/file/476716148442.pdf.

[27] Charlotte Bydler, The Global Art World Inc: On the Globalization of Contemporary Art (Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis, 2004).

[28] Nicolas Bourriaud, The Radicant, trans. J. Gussen and L. Porten (New York: Lukas & Sternberg, 2009).

[29] Marsha Meskimmon, Contemporary Art and the Cosmopolitan Imagination (London: Routledge, 2011).

[30] Nikos Papastergiadis and Meredith Martin, 'Art biennales and cities as platforms for global dialogue' in Festivals and the Cultural Public Sphere, L. Giorgi, M. Sassatelli and G. Delanty (eds), London: Routledge, 2011, pp.45-62.

[31] Hans Belting and Andrea Buddensieg (eds), The Global Art World: Audiences, Markets and Museums, Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2009.

[32] Terry Smith, Contemporary Arts: World Currents, London: Laurence King Publishing, 2011.

[33] Nikos Papastergiadis, 'Can there be a history of contemporary art?' Discipline 2 (2012), pp.152-156.

[34] Isabelle Stengers, Cosmopolitics II, trans. R. Bononno (Minneapolis: Minnesota University Press, 2011).

[35] Stuart Elden, 'Introducing Kostas Axelos and the "World,"' Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 24 (2006), pp.639-642.

[36] Gerard Delanty, The Cosmopolitan Imagination (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), p. 20.

[37] Nikos Papastergiadis and Victoria Lynn, eds., Art in the Global Present (Sydney: UTS Press, 2013).