Essays

As in an Ocean

On Nikolaj Larsen's End of Dreams

In death, as in an ocean, all our slow and swift diminishments flow out and merge. Death is the sum and consummation of all our diminishments: it is evil itself – purely physical evil, in so far as it results organically in the manifold structure of that physical nature in which we are immersed – but a moral evil too, in so far as in the society to which we belong, or in ourselves, the wrong use of our freedom, by spreading disorder, converts this manifold complexity of our nature into the source of all evil and all corruption.[1]

– Teilhard de Chardin, Le Milieu Divin

'Although migration has been a recurring theme in my work in the past few years, I don't really want to be known as the "migration" artist,' Nikolaj Bendix Skyum Larsen explained once. We could propose that it is this very ambiguity in Larsen's long-term artistic project that parallels the inherent fluidity of the situations with which he engages: specifically, the daily realities of current immigration. In avoiding any signature statement or didactic intention, Larsen allows the full resonance of his subject matter – its moral as well as practical complexity – to engage and ultimately imbue the audience's experience.

This approach is fundamental to Larsen's practice. Indeed, the medium for which he has until now been best known – the documentary film – occupies a notably open and arguable space, deliberately unclassifiable within such binaries as commercial/educational, or mainstream/marginal. Within the long history and theory of the documentary – itself the site of particularly nuanced academic debate as to the status and seniority in relation to film fiction – questions of distribution and context have always been paramount. From the very first film, those factory workers of les frères Lumière, to the most popular reality TV dramas of today, the question has always been for whom these images are being made and displayed, along with all the many assumed and actual distances and differences between filmmaker, subject and any final audience. These issues of participation and privacy, realistic terms of payment and celebrity, public exposure and exploitation, the inherent power of the viewer over the subject, are now as regularly debated in the context of Keeping Up With The Kardashians as they were by the Maoist Dziga Vertov group whilst filming at union car assembly lines.

Larsen has made a series of documentary films and in doing so has always insisted on leaving any ultimate definition open, operating as works of art within the network of such contemporary practice whilst being equally suitable to broadcast on a national TV channel, shown in cinemas, or presented at documentary film festivals. 'Why are these works of "art" rather than just documentary films?' is a question Larsen openly embraces and engages, exploits even, rather than rejecting with the customary arrogance of many pan-international Biennale participants. If you want these to be 'documentaries', then they can be, if you want to show them on Public Broadcasting or the BBC then their creator would be delighted, but so far they have been mainly diffused through contemporary art channels, where their audience is both more specific and presumably less conventional.

That said, Larsen's films would have to be located within the more sophisticated reaches of the documentary tradition, than most standard TV fare, their visual flair and aesthetic impact recalling perhaps Bill Viola or Charles Atlas, Raymond Depardon and Abbas Kiarostami rather than your average prime-time camerawork. 'I don't make films that have a specific duration and which are almost scripted beforehand,' Larsen explains. 'I never use voice over or narration, and they don't have the structure to put advertising within them. I never know exactly what the film will be before I start the production and what the right formatwill be: it could be three screens in a gallery space, or a single screen for the cinema. These things are clarified while I shoot the film and in the post production phase.'[2]

For the last decade, Larsen has worked almost consistently with the same director of photography Jonas Mortensen, and the same sound designer Mikkel H. Eriksen: all three of them Danes who studied whilst living together in London, and their contribution is essential and inseparable from Larsen's own vision. Indeed it is partly thanks to Mortensen and Eriksen, who are both professional full-time experts in their respective fields, working on every sort of big budget project whilst committed to their old friend's work, that Larsen has managed to achieve a series of films with the technical excellence of major production at a fraction of the cost. Because though, paradoxically, the dissemination of a film today through art world channels is probably much easier and more rewarding than having to battle through what remains of existing mainstream film distribution, there is still a quantitative difference in such potential funding. As Larsen puts it: 'Funding for a "real" documentary would get £70,000 whilst as an art project you might get £7,000, and that's when you're forced to think creatively. Just when does documentary film become art, there is always a soft border between the two.'[3]

Several of Larsen's films have been subsequently projected on the classic cinema screen, notably his Portrait of a River (2013) about the Thames Estuary, a depiction of the waterway and its history that evokes the work of Joseph Conrad, opening out through the industrial blight ofLondon's Docklands into the mouth of the sea itself. End of Season which was filmed in 2012 in Üyüklütatar Köyü, a village by a crucial border river between Greece and Turkey, was a project that ended up being very different in terms of its original intention: dealing with other types of migration rather than its initial subject matter of people smuggling, demonstrating Larsen's willingness to accept the vagaries of chance and circumstance. This film received its world premiere in the local café, being shown to its actor-character-villagers, making it clear that this film was for them as well as about them, their participation central to its premise, its narrative generated by a promise of trust. The importance of such participant involvement, whether in giving cameras to the 'subjects' themselves to let them film as they wish or merely in the celebratory screening of the finished work amongst its constituents, is a central tenet of community documentary practice as it has evolved from radical cinema verité theory.

Likewise, Larsen's film Tales From the Periphery (2010) assembled from footage shot by stigmatized second-generation immigrants residing in infamous housing estates in the outskirts of Paris and Århus in Denmark, sits squarely within a well-established activist cinema format. Similarly Promised Land (2011) was created as both a multi-screen installation and as a new edited version for single screen. At 47 minutes it was the standard length of most 'hour' long TV documentaries, and its subject matter, a diverse group of young migrants who will go to any length to cross the Channel to enter Britain from Calais, suggests a long lineage of such films. However, not only does the lushly rich cinematography evoke an entirely different cinematic tradition, closer to Hollywood than cinema verité, but the fact it was commissioned by the Folkstone Triennal, and projected there in a specifically created space, just across the channel from where shot, shifts its status.

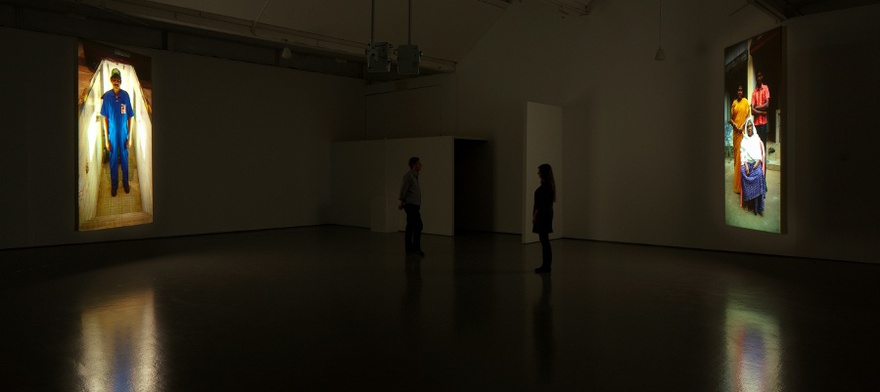

Hence with one of his best-known projects Rendezvous (2009), Larsen's film was specifically conceived as a two-screen installation, broken up temporally and physically across these opposed planes, designed to match both process and subject; Indian families who are forced to send their breadwinners to the Gulf region to work as labourers, and thus support their relatives back home. Rendezvous, which recreated the gap of time and place between the workers and their families at home, transformed the assumed hierarchy of the 'gaze' in allowing the immigrant worker and their distant family to seemingly look at each other, establish their own visual relationship, their haptic kinship, in some space beyond the voyeuristic eyes of the art spectator. In such a context, Rendezvous could only really be appreciated as a physical work through which one could move, shifting point-of-view and partial participation according to one's placement within this split environment. As such this was clearly a 'work of art', even specifically obeying the assumptions of many 'biennale' installations, indeed it was a great success at the 2009 Sharjah Biennial. Indeed, though technical innovations such as the 360 degree Imax screen or the advances of Lucas sound not to mention the revival of a more advanced 3D system and even 1970s split-screen stylistics have – to some extent – blurred the parameters of classic cinema viewing, the art world 'installation' experience still remains apart.

These basic boundaries of distribution, placement and physical presentation, which have so far divided the contemporary artist who works with film from the 'professional' filmmaker in their own separate ghetto, are in a state of increasing dissolution and seemingly daily further dissolving. This is perhaps partly because so many artists have now made feature films which are shown in high street cinemas and on primetime TV channels, and partly because opportunities for creativity and circulation are so much greater in the contemporary art system than in that moribund classic distribution chain; precisely as high street cinemas and mainstream TV channels are shrinking and vanishing daily, the art world seems to expand with unlimited resources and audiences.

Indeed the story of how experimental, avant-garde cinema was rescued from its certain death by the exponential expansion and inclusive generosity of the art system, is a salutary lesson in community and context; works for which it had become impossible to find an audience in the movie-house, whether Stan Brakhage, Robert Breer or Paul Sharits, finding new followers when shown upon free-standing screens in galleries and museums, with the added advantage that one was thus no longer obliged to sit through their duration, that they were presented as independent works, paintings in time.

Like the myth of King Midas it seems that the current art world can 'turn to gold' any sort of project from any other previously distinct field of cultural practice, for once it is presented and officially recognized – obviously the hardest part – as being 'contemporary art' then its collector-supporters and willing patrons are apparently limitless. Thus the art world has increasingly come to nurture and sustain all sorts of 'refugees' from other disciplines who have found funding and official support, which is signally lacking in their own traditional communities. Thus it is not only filmmakers who have subtly moved over into the art world, but choreographers and dancers, urbanists and architects, composers and musical performers, novelists and writers, typographers and designers, as it increasingly looks as if 'contemporary art' is the only fiscal game in town.

An interesting example of such a shift could be seen in the practice of Theaster Gates in Chicago, which I would argue could be directly compared to that of Larsen, not least in using what might be termed 'liberal guilt' to extend and complete the eventual reception of the work of art, to close the celebratory circle of audience and activist. Thus Gates, who could not find sufficient support for his initial work as an entirely un-ironic ceramicist, deliberately moved instead into the 'conceptual' arena and came to emphasize his African-American identity, openly playing with racial assumptions and their subsequent rewards within an almost entirely white collector audience. Most importantly, Gates came to appreciate that by the marketing of actual physical objects, the selling of individual certified and signed 'works of art' he could in fact support his entire project of urban regeneration and architectural restoration throughout his Chicago neighbourhood. As Jeffrey Deitch comments, 'His special fusion of art and community activism has made him the kind of artist that people are looking for today.'[4]. Gates had a notable success at Documenta 13 in Kassel in 2012 with work Gates described as a 'conversation about displaced peoples' and likewise with such installations as Accumulated Affects of Migration featuring fragmented debris from a house demolition within his neighbourhood. In Gates' own words: 'I couldn't have imagined that a piece of fire hose or an old piece of wood or the roof of a building would have gotten people so wet that they would want to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars on those objects.'[5].

Larsen's use of actual objects, indeed quite literally 'wet' objects, in his large-scale installation End of Dreams (2014-ongoing), initiated during a residency produced by the Rome-based arts organization Qwatz, moves his practice into another wider mode, not least dealing with issues of traditional sculpture as well as the fetishized commodity as thus construed by Theaster Gates. For as with Gates' Accumulated Affects of Migration, Larsen is presenting debris and wreckage produced as by-products from the process of his project within the context of the sacramental objet d'art, and presumably allowing them to be sold to help fund the entire endeavour, closing the loop of this long-term undertaking. Of course Larsen's screens on which he plays his films are also independent physical objects, whilst the films themselves are signally not objectifiable, even whilst marketable as limited-edition works of art. The issue of the film-as-thing (there must be a German word for this) has long haunted cinema theory and practical collecting, with actual metal cans of 35mm stock once being bought and sold as the embodied 'film' itself by museums and institutions. By contrast the objects that Larsen exhibits as part of End of Dreams are characteristically sculptural and built as such, by hand, from wire armature and concrete canvas, a material much deployed in disaster zones, like any artisanal sculpture. They are, however, not as initially intended, for accident, error and nature have all had their way with them, Larsen exploiting this unexpected development, a freak storm, to produce a previously unanticipated and finally fortuitous new work. Working with chance, rather than against it, Larsen has pushed his work into an even more radically poetic juxtaposition between cinema and sculpture, image and object, further emphasizing the ambiguity of intent and reception that underlies his practice.

This is not the first time that Larsen has created seemingly sculptural figures as part of a film installation, for in some ways End of Dreams was originally intended – in its planned form – as a reprise and extension of an earlier work. This work, Ode to the Perished, was created in 2011 and made a notable 'splash' – pun intended – at the 3rd Thessaloniki Biennale where it was dramatically installed in a religious building that had previously been both a synagogue and a mosque. For this work, Larsen built 12 shapes, objects subtly suggestive of a human body in mourning shroud or funerary sheets, fashioned from chicken wire and then covered by concrete canvas, which as aforementioned, is a material commonly used as key infrastructure for disaster relief. These 12 objects, which surely nobody would object to calling 'sculptures', were then immersed in the Aegean Sea for months developing the same patina of algae that objects floating in the sea over long periods acquire. These 'organisms from the Aegean Sea', as they were described in the technical data on the piece, were essential to the visual and tactile success of the work – not only direct evidence of their actual immersion but also resonant as unpredictable and entirely natural additions to the original man-made structures, celebrating the ocean's own power.

The 12 encrusted and corroded objects were then hungfrom the chapel ceiling, their suspended vertical forms suggesting everything from Goya's Disasters of War (1810-1820) to some factory-farmed noxious larvae whose eventual hatching one would not wish to witness. But above all else, literally above all the visitor heads, these dangling cocoons echoed the human dead, whether Christ in his winding sheet or Egyptian mummies. But the location of the installation, in Greece, was as vital to its accumulated potency as the very shadow and scent of the actual objects, for these suspended shapes were seen there to relate directly to the thousands of migrants who regularly cross the Aegean Sea between Turkey and Greece and often drown in the process. As an accompanying text explained; 'Operated by human trafficking mafias, they fill the vessels (often beyond capacity) with migrants willing to risk everything to reach the shores of the European Union. Often, the migrants' journeys end in peril – drowned at sea.' As such the entire installation, especially mounted in this sacramental space, acted as both emblematic and elegiac evidence as 'to why people have to flee their war-torn homes in search for a new safe place to live.'

Initially, End of Dreams was to have certain superficial similarities to Ode to the Perished, most obviously through the creation of the same figural objects out of wire and concrete canvas. Instead of 12 such sculptures, the location of the work was very different, namely the Tyrrhenian Sea in Calabria, off the western coast of Italy. This is the principal route for smuggled immigrants from North Africa to reach Italy and European territory. 'More than 20,000 people died in the last 20 years while trying to reach Italian shores. 2,300 lost their lives in 2011, about 700 in 2013,' said José Angel Oropeza, Director of the International Organization for Migration (IOM) coordinating office for the Mediterranean. 'Too many deaths, too many hopes drowned in the strip of sea which separates North Africa from Europe.'[6]

Originally, Larsen planned to immerse these 48 'sculptures' in the Tyrrhenian Sea for just four months, starting on 8 June 2014. But nature had other plans, as an unexpected and unusually powerful storm destroyed the wooden raft to which the objects were attached, severing the connections and sending them plunging to the bottom of the sea without any obvious means of retrieval. The parallel reality, the metaphoric potency, of this unanticipated destructive tempest compared to the fate of the actual refugees, likewise at the mercy of the weather, transformed the whole project into a perfect paradigm of 'life imitating art imitating life'. Instead of merely pulling these figures back up onto their raft after they had been suitably weathered by the planned and supervised period of immersion, Larsen was going to have to actively track, discover and somehow rescue these missing, stranded beings. Realizing the aesthetic possibilities and the ultimate resonance of this brutal shift in fortunes, Larsen decided to use a local underwater cameraman – art student, Giuseppe Politi – rather than his usual audio-visual collaborators (although Mikkel H. Eriksen will create the sound design), to find and film as many of the underwater sculptures as he could. So far, less than half, have been located but the resulting footage proved unlike anything else in Larsen's oeuvre, closer to a Surreal organic poetry than anything in the documentary tradition. Likewise, rather than just exhibiting the 'figures' Larsen will dredge and display the remains of the shattered raft, not to mention sections of the vibrant coloured cords with which they had been attached.

Thus, thanks to the very vagaries that make this crossing so dangerous, Larsen's project had been entirely transformed. Rather than being a literal 'revival' of an earlier work, it becomes instead a celebration of the larger mystery of storm and sea. 'I was initially slightly worried that End of Dreams might seem too similar to my Ode to the Perished,' explained Larsen. 'I wondered if I was just repeating myself, although there are obvious differences. To begin with, 48 figures are very different to just 12, in the same way that the Tyrrhenian Sea is very different to the Aegean, the former being used by North Africans, people from South Sudan, Eritrea and recently from Syria, whilst the latter saw refugees from everywhere from Iran to Afghanistan.'[7] The smaller number of figures is entirely appropriate as, by now, the Aegean is less popular as an immigration route: the direct result of much heavier policing and preventative construction work along the coasts. These are the statistical realities, the factual research, from which Larsen's works are abstracted, like any economic 'abstract' built from fact. 'But this new work also does something else simply because it comes after another three years, it is an art work made by someone with all the benefit of those three more years of work experience and knowledge.'[8] Another practical difference is that the figures were suspended hanging down, vertical, in Ode to the Perished, whilst in End of Dreams they are horizontal, still suspended, hanging as if between time and place, but their new alignment makes their association with corpses, the morgue line up, all the more evident, somewhere between the shroud of Mantegna's foreshortened Christ and Maurizio Cattelan's funereal Carrara marble forms.

The conditions underwater: the storms and sand dramas and the entire eco-climate of this usually unseen world, brings a completely new aesthetic dimension to End of Dreams, as captured by Politi, who descended more than eight times to search for the sculptures, locate them, and then film them in situ, observing how they were changing in their immersive environment as scattered on the seabed. There is as much emphasis on the 'drone-like' recorded scanning of the sea bed from above, like a military surveillance report, as on the magical aura of the surviving objects in their abject dissolution and the beautiful orange ropes used to tie them to the rafts like umbilical cords floating through womb water. Through the search for these objects one can recognize their shrouded, obscured forms as primeval body bags, mummies, and deep seaarchaeological finds. Both the location and retrieval of the sculptures, as played out through this installation of some eight orchestrated screens, give play to the most artistic side of documentary production, as close to Cocteau as Cousteau. Selected and edited down from countless hours of footage, the film alternates between sections scanning the seabed and an intense focus upon the sculptures that Politi documents on his search.There is also engaging footage of nautical buoys hooked to concrete anchors, the remaining fragments of the dilapidated raft,an old packet of cigarettes, drinks cans, a rotting old shoe, a shirt, images literally 'anchored' in our times, to the 'now' of this real-time investigation as well as its archaic associations.

Rather than a single screen narrative story, this is instead as much of an immersive environment as the sea itself which we see on every side of us, engulfed as we are in the aquatic screens and carefully composed audio, immediately aware that there is some kind of search going on and that we seem to have become part of it. The experience is closer to the metaphoric minimalism of a fiction such as 'Gravity' than the prosaic, grainy ordinariness of the actual moon landing original footage. Larsen naturally found this underwater film work challenging to direct, sitting as he was 3,000 kilometres away in his Paris studio, and he was obliged to take on all the vagaries of trial and error and long distance remote control. The end result is surprisingly lyrical and engaging, shot at 50 frames per second it generates a soft, slow movement, varying between the revelation of the buried sculptures and the skimming of the surface of the water, like a drone surveying an area where surely something bad has happened. In a revelatory comparison Larsen associates this footage with one of his favourite Modernist works of art: 'There is the famous Rothko room at the Tate, originally created for the Four Seasons restaurant in New York, and when I lived in Peckham and was going to Chelsea Art School I would always cycle via Pimlico and go see it,' Larsen recalls. 'I hope to createa similar spiritual experience to the countless times I've seen this Rothko – this weird sadness, introversion, to experience something that one doesn't really understand but which grants this tangible feeling. Thus, it is in many ways a relief for me that End of Dreams is now not so specifically about migrants. I originally wondered if I should even do a soundtrack interviewing these specific migrants. But if it is kept spiritual it becomes something bigger, less specific, not documenting someone else's experience but instead granting this quiet, gentle, slightly sad mystic spiritual experience – a space for contemplation.'[9]

But within the physical space of its deployment, and the larger space of its generative atmosphere, this film installation cannot be separated or analyzed aside from the totemic objects on display, those very objects whose discovery and rescue, resuscitation, form the oblique storyline of the surrounding audio-visual spectacle. In thus what seems an improbable, or unnecessarily formalistic exercise in criticism, the latest work of Larsen, previously categorized within a post-modern, multi-media practice of film and installation, must here be considered as actual 'sculpture' and in an archaic, if not almost 'classical' mode. Here is a literal 'body' or 'bodies' of work, as if ex-votos created to ask for future safe passage, or cocoons for the imagination from which will be born, emerging slowly in the mind of the viewer itself, both as the story of their own wreckage and as a phantom echo the tragedy of the actual human wreckage they parallel.

Larsen hopes that at least 20 of these willbe 'saved', here the implication of some spiritual salvation being generated by not only their life within the sea – the original and central human metaphor as befits our first birthplace – but their anthropomorphic resonance, their aura of the ancient and reverent, the very fact they still exist. In almost a reversal of the myth of Pygmalion, in which the sculptor breathes life into his built work, Larsen has seemingly conjured the spectre of death, the entropic force which governs the eventual dissolution of our own world and our own bodies, through three-dimensional mimesis. As some 'Ode to Entropy' these sculptures have taken on a 'life of their own' by their unexpected departure to the bottom of the sea, which has become a 'death of their own'. This is an act of abandonment and abjection outside the control of the artist and beyond his initial intentions, as if the artist-God were faced with the disobedience, the revolt of his own creatures, their loss of innocence in such independence, their final fate dependent upon the magnanimity of his rescue. The objet-matrix from which these creatures have been built has been superseded, subverted, by the very nature they were initially built to mimic, as if nature must have its revenge on such mimesis, thus making real this parable of the drowned within its own dangerous domain, as if summoning the archaic deities of this ancient part of the world and all their proud wrath.

Whether washed up on the beach, quite literally 'washed up' or laboriously hauled from the sea bed, these sculptures, some with moss growing on them, a layer of organic sediment acquired in their rebellious adventure, generate a potent magic as totemic, auratic presences. Originally these seemed skeletons of human proportion made of wood, chicken wire and draped concrete canvas, tied with white rope to hold them together, but now with so much sea-life growing upon them somehave lost their features, lost their looks. Now with their figurative associations blurred by the accumulated organisms that have built a new existence upon them, these objects could be read as proto-human, as some homage or votive offering to the origin of the human species, emerging so slowly from the protean sea bed, or as symbolic fertility figures offered to the sea in the hope of its granting further life. After this unplanned six months of 'weathering' Larsen has kept their still organic curved shapes and, in deliberately not cleaning them up, refusing all censorship, whatever being found and in whatever state being exhibited. Even once out of the water and kept in a warehouse to dry they have continued to develop their own separate ecosystem, as barnacles and moss, seaweed and sedimentary growths elaborate their existence.

With their richly associative and non-specific historically suggestive aura these objects cannot but conjure the ancient figures which once populated these lands, or at least passed amongst them, those Greek and Roman sculptures which were once traded through such straits, acting as a strong summoning of the ghosts of those great archaic empires. Recalling local archaeological discoveries, the relatively regular emergence of important lost sculptures from the sea bed, Larsen's figures thus make a direct link to that other flourishing Southern Italian illegal trade, the smuggling of stolen or unauthorized antiquities. Thus, two separate worlds of clandestine smuggling, of actual people and of sculptures of people, are brought together by these amorphous shapes in their resemblance as much to corpses as to the encrusted remains of some distant artist's handiwork. Though antiquities smuggling has long been a vital and highly profitable business in this part of the world, its ties are more to Italian organized crime than to the largely North African gangs that operate in people smuggling. Presumably there must somewhere be some overlap between these two parallel criminal activities, here conjoined in the matrix of Larsen's installation, between the human treated as an object and the object treated – and valued and smuggled – as the human it represents.

The drama and 'theatricality' of Larsen's objects, refusing the status of actual actors but perhaps evoking the precepts of Michael Fried in his seminal essay on sculpture and theatre, are adjunct to his ultimately educative intent. Along with the exhibited debris from the rafts to which they were once attached, suggestive of everything from the Raft of the Medusa by Géricault (1818-19) to Jeremy Deller's exploded suicide vehicle, this carefully orchestrated display is intended to serve as a catalyst for debate and discussion. Indeed, like Deller's wrecked car which was toured around America to promote a genuine 'dialogue' around issues of US involvement in Afghanistan and Iraq, Larsen hopes that End of Dreams will move across Europe, heading surely north following the pattern of the original immigrants, and provoking a serious discussion of its manifold implications.

This trajectory, of the artist as well as the refugee, the actual journey as well as the creative itinerary, could be termed 'political' but only in the sense that national politic have consistently interfered with what is otherwise a very simple operation, the arc of movement, and thus transformed these inherently straightforward voyages into one of the most fraught political issues of contemporary times. As always, one must distinguish between the simplicity of intention and difficulty of achievement, perhaps using that classic example of the moon landing, something inherently simple in its aim, to have a human walk on the moon, and impossibly laborious in execution. Likewise, the desire of the immigrant, to live somewhere with better prospects and a safer everyday existence, is understandable and logical to almost everyone, whilst the reality of their attempts to do so prove horribly complex, dangerous and controversial, generating legislation, condemnation, philosophic debate and political action.

As Larsen concludes: 'This is not a work just about contemporary immigration.I trust it will also evoke other eras in history where people were continuously moving, displacing themselves, this issue of mass movement has been just as pressing before, whether with the Ottoman empire, the Roman empire or indeed in the gigantic migratory patterns after the Second World War. Rather than an entirely topical political subject, I would much prefer if this project was understood as a pointer back to other times in history, to the eternal complexity of such historic migration, almost as an archaeology of our human society and its long status of geographical flux.'[10]

The artist would like to thank the team at Rome-based art organization Qwatz for their incredible support during the creation of End of Dreams.

[1] Teilhard de Chardin, Le Milieu Divin (London: Collins, 1967), p.82.

[2] Nikolaj Larsen, Personal Interview, Paris, 15 October 2014.

[3] Ibid.

[4] John Colapinto, 'The Real-Estate Artist', New Yorker, 20 January 2014 http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2014/01/20/the-real-estate-artist.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Stephen Ogongo Ongong'a, 'Does EU have political will to stop deaths in the Mediterranean Sea?' Africa News website, 1 July 2014 http://www.africa-news.eu/immigration-news/italy/6166-does-eu-have-political-will-to-stop-deaths-in-the-mediterranean-sea.html.

[7] Nikolaj Larsen, Personal Interview, Paris, 15 October 2014.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.