Essays

The Many Afterlives of Lulu

The Story of Bahrain’s Pearl Roundabout

The pearl teeters; it rolls lazily to one side as the monument's six concrete legs start to fall apart. [JUMP CUT – IMAGE MISSING] Between broken bones, the pieces of the pearl's cracked skull lie in sand and rubble.

Squaring the circle is a problem handed down from the Ancient Greeks. It involves taking the curved line of a circle and attempting to draw a perfect square from it; a task that for centuries mathematicians were convinced they could figure out. In the nineteenth century, when the problem was proved unsolvable, the phrase to 'square the circle' came to signify an attempt at the impossible. But in 2011, within days of the most sustained and widely broadcasted protests in Bahrain's recent history, a circle was named a square. The once unassuming Pearl Roundabout or Dowar al Lulu, famous in the international media as the site of the Gulf's answer to the 'Arab Spring', became Bahrain's 'Pearl Square' or Midan al Lulu.

A month of mass protests later and the roundabout was razed to the ground. In its death, the Pearl Roundabout took on a life of its own, becoming the symbol of a protest movement; the star of tribute videos and video games, the logo for Internet TV channels and the subject of contested claims, rebuttals and comments wars. These manifestations of the roundabout - multifaceted, changing and often contradictory - produce a haunting rhetorical effect, instigating debates fuelled by images of past and on-going violence in Bahrain's history. In its afterlife, Lulu continues to act stubbornly in resistance to the state, despite the government's attempts to shape the monument's memory to serve its own interests, going so far as to tear the monument down and rename the ground on where it once stood. Today, Lulu is a powerful symbol for thousands of people recasting their ideals in the monument's image: a 'public space', or midan – Arabic for civic square; one that no longer exists as a physical 'thing', but rather, lives on as an image-memory.

The Birth of Lulu

The Pearl Roundabout was a central roundabout in Bahrain's capital Manama. At its centre stood a 300-foot tall monument, milky white and built in 1982 to commemorate the 3rd Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) Summit, a meeting of Gulf States. The monument's six white, curved 'sails' represented each GCC member state: Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. A large cement pearl sat atop these sails in homage to the region's former pearl diving economy, which attracted the likes of Jacques Cartier to Bahrain's soil. But with the pearling industry in decline and tanker traffic drilling and dredging the region's sea beds, destroying them in the process; the GCC looked forward to a new era of economic development. The 1982 summit also launched the Gulf Investment Corporation, a $2.1 billion fund, and a military partnership between the GCC states: the creation of the Peninsula Shield Force or Dr'a Al Jazeera. This treaty codified what is now the pillar of the GCC's military doctrine: that the security of all the members of the council relied on the notion of the GCC operating as an 'indivisible whole'.

To celebrate the end of the momentous summit, a cavalcade of cars took officials to the unveiling of a plaque commemorating the construction of the 25 km causeway linking Bahrain to the mainland Arabian Peninsula. King Fahd bin 'Abd Al 'Aziz of Saudi Arabia and Shaikh Isa bin Salman Al Khalifa, Emir of Bahrain, stepped forward to release the black drapes. Bahrain, at least in theory, was no longer an island. After its construction, Lulu became the chosen pearl in Bahrain's crown: the star of souvenir shops. It was, for a while at least, a symbol of Bahrain, sanctioned by the government, photographed by tourists and its image presented on neon shop signs.

Drive around Bahrain in January 2013 and there are symbols everywhere. As the 21st Gulf Cup (a biannual football tournament) was held at Bahrain's newly revamped Shaikh Isa Sports City, the highways and streets are lined with flags and symbols of the Gulf Cooperation Council, marking a summit meeting held in Bahrain in December 2012. Yet, all over the island, behind trees covered in red and white fairy-lights, royal crests, billboards of smiling leaders and flags of GCC countries, we see walls. And on these walls are many images and symbols that counter the state sponsored GCC branding campaigns, especially in villages and smaller side streets in Manama. You will see graffiti scrawled in Arabic and in English, some of which you can read if you happen to pass by before they have been painted over. Through layers of paint, these walls bear the traces of a conversation, an argument. Images and names of political prisoners, cries for help, or calls to fight. The most popular word you see written on the walls is 'Sumood' – perseverance – stencilled or scrawled alongside hastily drawn pictures of the former Pearl Roundabout.

Roundabouts and Amnesia

Monuments are often inscribed with a desire to inculcate a sense of shared experience and identity in society. As markers of a nation's history, the state imprints its self-image on the citizens through the erection of such memorials to key historical events and figures. These ideas and messages can often become overlooked, their original meanings forgotten over time. 'There is nothing in this world as invisible as a monument,' historian Robert Musil wrote. 'There is no doubt that they are erected to be seen…But at the same time they are impregnated with something that repels attention.'[1]

Like many GCC countries, Bahrain is inundated with roundabouts featuring monuments of pearls, fish, falcons, sails and desert animals. Rather than featuring direct references to historical events or figures these monuments make up part of the visual language and urban inscription of national and regional identity in the Gulf. Key to this state-controlled image economy is the foregrounding of 'traditional Arab culture'. Emphasis is placed on the ruling family as representatives of the nation, which therefore privileges Sunni Muslim, male and tribal identities. Concurrently, Bahrain's historical influences from the wider Arab world, the Indian subcontinent and Persia are downplayed or ignored and any histories of struggle are silenced. Instead, whitewashed concrete pearls, fish, falcons, Arabian horses and the oryx are mediating national historiographies, as seen in the proliferation of official portraits of monarchs in public spaces and framed on the walls of most institutions in the region. Like the Pearl Roundabout, such symbols are used to construct an image of the state. As anthropologist Sulayman Khalaf describes:

Ruling families and their allies have invented and made use of cultural traditions, nationalism, authenticity and 'traditional' values to identify themselves as the guardians of authentic Arab values and traditions, and bolster 'dynastic political structure.'[2]

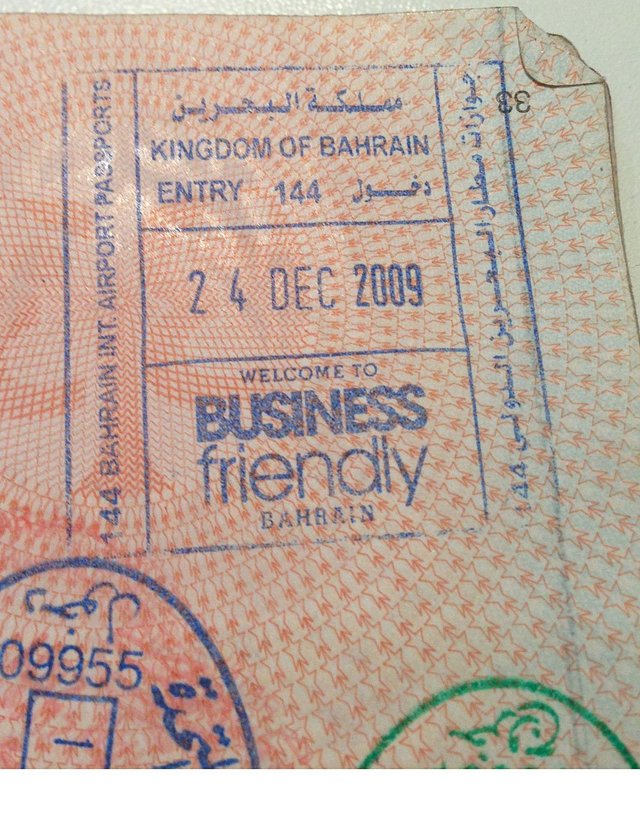

Yet by the early 2000s, with its various paint jobs and facelifts, the Khaleeji-modern Pearl Roundabout became dwarfed by the rise of the high-rises constructed around it; the Bahrain Financial Harbour and the World Trade Centre, for example – glittering monuments of progress and national prestige. Bahrain, seemingly got bored of its overused tagline, 'Pearl of the Gulf' and moved onto 'Business Friendly Bahrain'. These new, sparkling towers replaced the monument in an image conscious branding campaign, 'staging' Bahrain as a leading financial centre in the region,[3] a campaign that extended to the entry stamp at immigration and black cabs in London.[4]

Alongside the branding campaigns, the history of Bahrain's pearling industry became an integral part of the Ministry of Culture's remit. Cultural heritage became framed as a strategic positioning of Bahrain in the global imaginary. The rhetoric of Bahrain National Museum's 'Investing in Culture' campaign, for example, describes how cultural investment bolsters a 'process of forging cultural links and global communication.' [5] The government's investment in branding campaigns and strategies of self-representation internationally reflects the importance of controlling and maintaining an image of the country, bolstering the government's construction of a national identity that is itself intimately linked with Bahrain's position in the global sphere of international foreign investment. This experience of advanced neoliberalism in Bahrain has caused the widening of the gap between poorer citizens and those who have benefitted from the island's position as the 'freest economy in the Middle East'.[6] But Bahrain's totalizing mythos has been maintained by the suppression of dissent and a privatized urban infrastructure designed to sustain a façade of stability; of Bahrain as a business-friendly tourist hub.

Indeed, as opposition movements in Bahrain have been active for decades, so has the state's security apparatus, which often targets marginalized low-income areas and subjects dissenters to torture and detention.[7] These violent histories of struggle are ignored and often denied mention in state narratives. Bahrain's contested history is strictly controlled, requiring approval from the Ministry of Information[8] – many historical studies and publications have been banned and any counter-narratives silenced.[9] At the same time, increased privatization has brought with it the shrinking of public and common land, including the disappearance of public beaches. Large gatherings can only legally[10] happen within neighbourhoods and private spaces and Bahrainis have found it difficult to access public space in which to gather, let alone voice dissent.[11]

As writer and architect Todd Reisz describes:

…roundabouts offered Bahrain an advantage: open space without extending those spaces for human use. An expanse of green parkland is isolated by an undying stream of traffic (…) roundabout circles are not places; they are voids. In other words, Bahrain might have green spaces, but there are few public spaces needing to be monitored.[12]

An example of this is in Manama's old souq, located in an area now referred to as being near the 'Fish Roundabout'. This rundown neighbourhood of the souq, near hardware shops and the three-star Caravan and Adhari Hotels, features a small fenced garden with a roundabout at one end with two intertwined fish. It was once home to the first municipality building in the region, built in 1923, and which hosted an elected, municipal council. Surrounding this building was a busy open boulevard flanked by markets, the souq alaham or meat market, cafes and small guesthouses. The market was, in all senses, a civic space with a thriving political life. It was here that, in the days of British rule, a series of labour protests and gatherings were held: a movement, which grew stronger in the 1970s during the rise and fall of the first National Assembly. Today, the fish roundabout – with a bench that is often empty and cars and scooters parked around it – makes for a quiet corner of Manama. No physical markers of its history remain; there are no traces of this place ever being a politicized public space.

Thinking back to the events that took place around the Pearl Roundabout, spurred on by uprisings in other cities in the region,[13] this was a social alliance that had been – in part – summoned up via Facebook. On 14th February 2011,[14] tens of thousands of people joined in a demonstration resulting in the Pearl Roundabout's occupation. As traffic stood still, the international media came to witness the Gulf's answer to the 'Arab Spring' and overnight, the government had lost control of it's carefully constructed image of a 'Business Friendly' Bahrain, as news networks broadcast images of the Pearl Roundabout surrounded by protestors demanding reforms. A circle was named a square. The naming of the roundabout as Pearl Square or Midan al Lulu in the international media, though initially seen by many Bahrainis as a laughable and ignorant mistake, soon became appropriated by some protestors, who saw it as an underlining of the roundabout's new figuration as a 'civic square' or midan.

The unprecedented occupation of the 'square' became front-page news internationally as Manama was brought to a halt. Within days, there were attempts by the state to quell the growing protests with tear gas and other threats of force culminating in a violent crackdown on the roundabout at 3am on 17th February 2011. Over four days, there were hundreds of injuries and seven civilian deaths. This harsh response surprised and radicalized many who had witnessed the events either first hand, in the international media, or through hundreds of shaky, panicked mobile phone videos posted on YouTube. Yet despite this heavy-handed repression, many defiantly returned to the roundabout, now a site of trauma and renamed Martyr's Square or Midan Al Shuhada by some.

As the battle over contested spaces continued, another battle was raging in the media, especially over the re-telling of the events of the 17th February crackdown on the roundabout. Overwhelmed by the unprecedented interest and reporting from the international media, international journalists were deported and none were let back in. The Ministry of Information and state TV began a campaign to discredit journalists and protestors using a tactical sectarian slant. While the international media spoke of pro-democracy protestors, the language of the state was of traitors, foreign-agents. The roundabout was referred to by its official name; the GCC Roundabout or Dowar Majlis Al Ta'awon. Days later, at the Al Fateh[15] mosque, one kilometre away from the Pearl Roundabout, a counter-rally was organized by an umbrella group named 'The Gathering of National Unity'. Tens of thousands of citizens waved Bahraini flags, with posters of the King held high, and a cable of thanks was sent from the King to the organizers of the rally. Meanwhile, hundreds were arrested including doctors, nurses, bloggers and journalists, and hundreds more lost jobs for being absent during the days of the protests.[16]

After a month of protests, martial law was declared. The Bahrain-Saudi causeway rumbled with the sounds of hundreds of tanks of the Dr'a Al Jazeera or Peninsula Shield. For the last time, the roundabout was cleared by force, main roads leading up to the roundabout were sealed off and villages were kettled by armoured vehicles. Days later, in a spectacularly reactionary move, Bahrain's State TV replayed scenes that would within minutes circulate the digital mediasphere. As the country watched from their phones/homes/computer screens, the Pearl Monument exploded into a pile of bones over the ruins of an occupied 'square'.

Attempting to reset the political clock, the image of the Pearl Roundabout began to be officially erased from public view; the 500 fils coin, engraved with the image of the Pearl monument, was taken out of circulation and postcards featuring its image were removed from tourist shops in the souq and official government websites. In an edited report with subtitles by 'Feb14 TV', one of the hundreds of Youtube channels that have emerged out of Bahrain since 2011, we see the footage by Bahrain Television with another clip of a press conference a few days after the broadcast. The video is one of the hundreds of the demolition of the Pearl Roundabout: an edit of the original footage of the demolition, aired by Bahrain State TV and followed by 'unseen clips', cut out of the State TV broadcast, of a tragic accident where a migrant labourer was killed during the hasty demolition. An abrupt wipe brings us to a press conference with Foreign Minister and prolific tweeter, Shaikh Khalid Bin Ahmad Al Khalifa, as the Foreign Minister explains how the monument was brought down because 'it was a bad memory'.

Such acts could be labelled as acts of Damnatio memoriae, literally meaning 'condemnation of memory' a practice that included the destruction of images of a person deemed by government decree an enemy of the state in the Roman world. Such a decree meant that the name of the damned was conspicuously scratched out from inscriptions, his face chiselled from statues and the statues themselves often abused as if it were a real person, while frescoes would be painted over and coins bearing any image of the blacklisted were defaced and any documents or writings destroyed. In demolishing the roundabout, it became clear to all who watched that this speechless stone monument, which had once bore witness to the Bahraini uprising and once symbolized state-sanctioned progress, had since become an enemy of the state. Its punishment was erasure.

Lulu Rising

[VIDEO: The ident for new satellite TV channel, Lulu TV]

With no monuments, roundabouts or coins to bare its traces, the Pearl Roundabout was removed from state narrative by a government hoping to create a clean slate with which to rewrite sanctioned memories post-uprising. The Pearl Roundabout's traces were re-inscribed for the last time when the area was provocatively renamed the 'Al Farooq Junction',[17] a barricaded, inaccessible traffic intersection. Two years after its destruction, the site where Lulu once sat remains inaccessible: all the roads leading to the newly built junction are blocked with riot police vans and soldiers. There are also signs strictly prohibiting photography.

But though it no longer exists in physical form, the Pearl Roundabout rises from the rubble not only through graffiti or as the logo for the 'February 14th coalition',[18] but also through the thousands of YouTube videos like this, channels, online images and digital parodies circulating the Internet. As with many historical examples of iconoclasm, such as the well-documented removal of Saddam Hussein's statues in Iraq in 2003, the official destruction of images, monuments and symbols – it can be argued – guarantees the production of images. As Paul Virilio notes, the mechanical reproduction of images are like ghostly 'clones' and a production of 'the living dead'.[19] In the case of Lulu, we see the Pearl Roundabout as an object resurrected and once again destroyed, time and time again in the footage of its demolition. In these digital images, we come into contact with the Pearl Roundabout's life and death: its image-resurrection and re-dispersal. Its inert material as an image can then be considered living, or at least 'undead' – an immortal activist, a martyr or an enemy of the state, instilling itself in the memories of the Bahraini people and mingling daily with some sort of collective consciousness.

Given the potency of the monument as a contemporary symbol, it is near impossible to destroy its image once it has been posted online, no matter how hard one might try to destroy it. These pearl-clones have the potential to wreak social and political havoc when caught in a circuit of meaning exchanges in online networks, thus producing new narratives and counter-memories. Like the 'mirror scene' in Sam Raimi's 1992 Army of Darkness,[20] where evil clones burst from the shattered pieces of mirror, the Pearl Roundabout might be positioned as the shattered mirror from which a multiplicity of spatially dispersed images emerge. Each image of the monument is presented on screens that are owned and viewed by individuals with their personal subjective relationship to the monument's image. In this, the Pearl Roundabout cannot be contained by a single point of view precisely because it means different things to different people.

As with objects, the image can act and function in multiple ways that shift continually across time and space, fluidly negotiating ever-changing subjectivities and realities. Today, a YouTube search for 'Pearl Roundabout' in Arabic yields 4,170 results and in English 1, 720; a Google image search has 71,900 in Arabic and 299,000 results in English.[21] Bahrain, although the least populated country in the region, was the subject of the greatest number of Twitter hash tags, with 2.8 million mentions at the end of 2011, while in Arabic it clocked 1.48 million hash tags.[22] Considering how Bahrain has been connected to the Internet since 1995 and rates of use were estimated at 77% in 2011,[23] the popularity of the #Bahrain hash tag and the proliferation of hundreds of websites, blogs, social media pages, have created online digital archives, which can only confirm that the virtual world has become a site of counter-memory and discourse. Alongside the unprecedented wave of media about Bahrain reported by opposition, government supporters and journalists, the Bahraini government was spending millions on international PR companies to counter a negative image.[24] The government was an early adopter of Twitter and YouTube at the start of the protests in 2011, populating news feeds and twitter streams with one line of argument. The social-media landscape of Bahrain is graphic, violent and controversial, making the scramble for answers and information about the ongoing protests increasingly difficult.

In his essay 'Nietzsche, Genealogy, History',[25] Foucault describes how counter-memory splinters the monolithic, and ruptures the homogenous narratives imposed by the powerful. Counter-memory allows 'scratched over', eroded, and repressed archives, documents and images to 'shine brightly' alongside those that correlate with the state endorsed images that support homogenous narratives of power. Unlike its status as a monument, silent and invisible, the post demolition image of the Pearl Roundabout is mutable, ever changing in circuits of meaning exchange. It does not fix or ossify, but rather, as Roland Barthes has written on the photographic image, 'blocks memory, quickly becom[ing] a counter-memory,'[26] precisely because it now exists as an image.

The Splintered Image

I remember the Lulu Roundabout as the tallest structure on the island. As a child, it seemed colossal and unapproachable; the car seemed to lean slightly as we circled its unusually large circumference. At its base were fountains and at night and on National Day and Eid, the monument would be lit up with colourful light shows. Seeing people on the manicured grass of the roundabout was rare, and those moments would often involve migrant labourers, on a Friday afternoon break, dangerously navigating traffic to get on the roundabout for that keepsake photo. I would peek out of my window dizzily, trying to look at the pearl, which seemed to vanish into the sky, fading from the field of vision, as we got closer.

As the Bahraini uprising continues, two years after the Pearl Roundabout was violently erased, Lulu has taken on a mythical status. And as we circle the roundabout like lost satellites, we bear witness to the multiple manifestations of this politically-charged monument both as a physical, exploding object, and as an explosion of digital files. A Google image search for the Pearl Roundabout only gives a glimpse of the vast production of discourses, truth-claims and narratives that the Pearl Roundabout generates. Photoshopped edits of the same recycled images of Lulu fill blog posts, articles and online forums focused on the topic of the Bahraini uprising. These images and videos of the Pearl Roundabout are often memorials of their own to the roundabout and of its occupation. The monument is often viewed nostalgically, such as in this 3D rendering of the monument with birds circling in a halo around its crown. The use of 3D recreations of the monument are also common, reanimating the roundabout as a martyr, featured in video games and hero videos, such as 'Bahrain Revolution', which ends with the monument emerging from the sea and a lone protester saluting it. In 'Children of Bahrain and their memories' we see another YouTube video that recreates a model of the roundabout and area surrounding it, built by children using rubber bullets and other weapons used by Bahraini security forces. Emotive, militaristic music is overlayed with images of this model and text blaming state violence for the violent memories of Bahrain's children.

The production, dissemination and consumption of images of the Pearl Roundabout and the discourses generated around these images is inherently tied to the narration of events that surrounded it during the uprising, not to mention its role in the raging political and ideological battles that have since emerged. The monument, once used as part of the state's image-economy, has been turned into a memorial for an uprising against the very state that created it. This is clear in the case of the many physical reappearances of Lulu in the streets of Bahrain. Through a practice of commemoration and reproduction, 'Lulu-clones' appear at various events and happenings, from sit-ins, protests and even religious festivals such as the annual 'Ashura marches. In this video from April 2011, filmed during the period when a State of Emergency was declared in Bahrain and rallies and protests were banned, activists leave a reproduction of the monument on a street as riot police prod it gingerly. Another action in June 2011, several policemen re-enact the demolition of the monument in an unwitting public performance at the A'ali village roundabout as they try to remove it. Aside from becoming both an act of defiance,[27] these commemorations share a common function: they aim to re-activate something that was once alive.

In its re-imaging and re-inscribing as a digital object, we see the distinctions between virtual and real blur as the image of the Pearl Roundabout is infused with multiple writings, rewritings, claims and memories by the state and citizens. An ubiquitous image, Lulu is the point of focus for the battles that have raged in the streets between citizens and state since 2011, but these discourses and narratives stretch far beyond the 2011 uprisings. They can be traced to descriptions of clashes between protestors and state security forces that have been going on in Bahrain since even before the March Intifada of 1965. Clashes and protests have long been described by the Bahraini government as a'amal shaghab: acts of hooliganism or a'amal irhabiya, acts of terrorism, while opposition groups describe the conflict as an intifada sha'biyya, or popular uprising. Online, these discourses manifest in blog-posts and on social media in an argument between the state, government supporters, commentators and those that oppose the government.

The 50-second clip of the demolition of the Pearl Roundabout, originally aired by Bahrain State television following the destruction of the monument has been used and reused in various and sometimes oppositional narrations of the Bahraini uprising. Here, Youtube user, 'mohammedalbuainain' produces a video overlaying text on the demolition video adding photos of faces of opposition figures with 'we made fools out of them' stamped on their faces, and a 'he he he' on top of the video of the roundabout collapsing, ending with a request to follow him on twitter at his user name @khalifa4ever, reflecting a view on the protests that echo a video depicting the occupation as a carnival, called 'The scandal of 'Dowar al Shisha' (Shisha Roundabout)'. The video - with a soundtrack of a child laughing - contains images of the roundabout with shisha, haircuts, food and even the appearance of Barney the Dinosaur, discrediting the protestors political motivations for the demonstrations. It ends with a text saying 'these people don't know the meaning of revolution or peace.'

In other videos, such as 'Dowar Al Mut'a', the mixed-gender occupation of the roundabout becomes the key point of contention, depicting the roundabout as a place of 'filth' and for 'mut'a', a temporary marriage custom permitted in Shi'a Islam.[28] Posted by 'BahrainShield', the film presents a montage of images taken after the 17th February crackdown and clearing of the roundabout. Sexually discrediting protestors is quite common among anti-opposition online comments as well as a strategy used by 'Internet trolls' to discredit female activists, who have had a key role in the Bahraini uprising, often making up more than half the participants in marches and street protests. On the flipside, those who supported the protests have also used this footage. It appears in 'We will return to Midan Al Shuhadaa (Martyr's Square)' by 'AlBahrainRevolution'. Dramatic music and heavy treatment of the original footage is edited alongside images of protests, riot police and state violence ending dramatically with a fire-explosion wipe and the Pearl Roundabout as featured in the logo for the 'February 14 Media Network', one of the many networks of citizen journalists disseminating media on the Internet.

In this pattern of image reproduction, the Pearl Roundabout's surfaces, textures and dimensions, are immersed in a pervasive cycle of images mimicking the thick layers of paint on the graffitied walls of Bahrain. These digital images, such as the videos discussed above, play out a 'war of ideas' where surges of support are set in motion both on national and global networks through the viral spreading of images, leaving it difficult for the government to defend its own strategic narrative. Yet the distinctions between reality and fiction become as difficult to identify as the boundary between original image and copy, especially when thinking about the endless, tampered images of the Pearl Roundabout consistently presented as evidence or validation, rather than a marker of fictitious, alterable entities. These constant re-appropriations invite us to rethink our relationship with the image, and its existence in the digital universe, where images cannot be destroyed because they exist in code. Digital images act like a membrane; the shiny surface of media-skin. And the challenge when viewing such pictures is not unlike the experience of Alice stepping through the mirror in Lewis Carroll's Through the Looking Glass. To cross over and back is to try to get through the media surface, saturated with violent, affective images depicting a complicated and dark reality. Such actions might serve to connect such things as memory and architecture, or the sense of place and the experience of struggle in a transaction between both sides of the screen.

Jean Baudrillard once described the image as the site of the disappearance of meaning. After 9/11, he wondered to what extent certain photographs had become parodies of violence. The question was no longer about the truth or falsity of images, but of their impact. This suggests that images themselves have become an integral part of conflict, protest, revolution and warfare. Today, Lulu has persisted in its presence as a symbol through the violence recalled in its image, from the martyrdom of protestors who died in the square and in the years that followed, to the violence upon the collective memories of Bahrain and the denials of its representation embedded in the roundabout's image. In this, Bahrain has a new monument with which to view its past and present violence: a monument that reclaims space for multiple histories and narratives to come together, from a censored homogenous state narrative to a symbol for an active, politicized and heterogeneous society. Thinking back to the Pearl Roundabout as I gazed at it from the car window as a child, to the images of it today, it seems the roundabout – this digital monument – has become a vanishing point of reality. The image itself has become violent.[29]

[21] 'Rise of Arab Social Media,' Zawya, 24 July 2012 http://www.zawya.com/story/Rise_of_Arab_social_media-ZAWYA20120724051637//