Essays

Knowledge Bound

Reflections on Ashkal Alwan's Home Workspace Program, 2013-14

In an industrial section of East Beirut, near the underpass beneath which trickles Beirut's withered river, a sun-parched pink building nestles between vast warehouses of car dealerships and timber factories.

Established in 1994 as the Lebanese Association for the Plastic Arts and invested in reengaging an artistic community with Beirut's public space following years of devastating civil war, Ashkal Alwan operates today as a platform for artists and theorists from all over the world. This original process of reclamation of spaces for art and debate, in public gardens and Beirut's sweeping corniche, was powerful in establishing a paradigm for critique and political discussion that still characterizes much of Beirut's artistic identity.

Ashkal Alwan, founded by Director Christine Tohmé, initiated the Home Workspace Program (HWP) in 2011, as a sister to the Home Works Forum, a multidisciplinary platform for cultural practices which occurs every 2–3 years, begun in 2002. While each Forum lasts for ten days, the HWP follows a full academic year, and operates as a kind of unconventional art school, accepting roughly 15 students a year who explore a curriculum, or series of thematics, developed by its Resident Professors. These are invited by the Home Workspace Program Committee; Emily Jacir led the course for 2011–12 and Matthias Lilienthal for 2012–13. Designed predominantly for emerging artists, the programme is characterized by the variety of the speakers and practitioners it invites to lecture, lead workshops and give masterclasses. Aside from the depth and rigour of this interaction, participants are mentored by established artists and thinkers as they progress their practice, and make use of the enormous warehouse space – equipped with studios, lecture theatre, editing suite and library – that Ashkal occupies in Jisr el-Wati. Participants are often expected to develop projects which culminate in an exhibition or alternative modes of reflection upon the year and the dynamics of the group.

This year, however, the Home Workspace Program looks a little different. The 2013–2014 curriculum has been devised and led by Jalal Toufic and Anton Vidokle, under the title 'Creating and Dispersing Universes that Work without Working'. Unlike previous iterations of the programme, whose limited numbers involved competitive application and required participants' commitment to a full academic year, Toufic and Vidokle have posited their programme as a 'free, experimental school',[1] with open registration and freedom of participation. For the first time, the group has the space for large numbers and students can join the programme for days, weeks or months at a time. The programme's theoretical thrust is driven primarily by Toufic's theoretical writing – on vampires, universes and mortals – and Vidokle's artistic concerns with work, labour, and history. The academic element of the programme is paralleled by its ongoing relationship with e-flux journal (Vidokle is one of its editors), and augmented by numerous visits from curators, artists, theorists and others (Adam Curtis, Hans Ulrich Obrist, Anselm Franke, Hito Steyerl) invited by the professors, and the development of independent projects that participants are encouraged to undertake simultaneously.

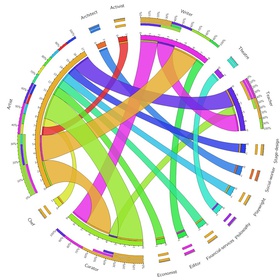

The year got off to a tricky start, when 'Chapter 1' (due to begin in September) was postponed over escalated security fears due to potential US action in Syria. It was November, therefore, before the programme opened officially – in media res, as it were – at 'Chapter 2'. Thus I find myself sitting in front of a vast blackboard on a beautiful afternoon in early November, watching Vidolke chalking up the week's schedule from his vantage point on a ladder. This is the first time everyone has met and introductions are made. Participant demographics are clear quickly, and surprise me – a much greater proportion of the group is international than I had anticipated. There is a swathe from Scandinavia, a clutch of Austrian/Germans, a pair of Icelandics, a handful of Brits, Spaniards, Italians, Eastern Europeans, and scattered representatives of Japan, Canada and Mexico. There are, of course, local Lebanese participants, and those from elsewhere in the Middle East – Kuwait, Jordan, Syria, Palestine and Libya. In what must be a contrast for the Ashkal Alwan staff who sit watching, there are 50 people gathered around the board, as opposed to 15. Initial introductions suggest the vast majority of the participants self-identify as artists, though more detailed presentations in a later workshop reveals almost everyone to be affiliated with multiple roles and fields, reflecting the fluid, multi-disciplinary nature of artistic work today.[3]

The staff at Ashkal Alwan admitted feeling emotional at this first meeting, moved by the fact that so many participants, both local and international, had travelled to be here in Beirut, despite security fears, and were energized by their arrival in the city and the space. It is now March, and with 'Chapter 3' underway (the first postponed chapter followed 'Chapter 2' in January), I hope to reflect on key questions which have emerged over the past four months, specifically in connection to the programme's relationship to pedagogy, and to space.

Those first few weeks of November were dominated by meetings, reintroductions, evenings in bars and meta-discussions about what exactly we were all doing here. Listening again to interviews I conducted with fellow participants over the first two months, a consistent theme in conversation was our collective grappling with the aims and intentions of the programme, and the ways in which these intersected our own expectations and desires. This became clear in a workshop given by Brian Kuan Wood, a week into the programme's start. Wood is the editor of e-flux journal, alongside Vidokle and Julieta Aranda, and has been invited to give workshops in every chapter this year. The first of these was given the title 'Narration and Absent Horizons' and was packed: 43 of us huddled in a circle. Wood invited everyone to introduce themselves, their interests and their work, to use these ideas as catalysts for discussion. The sheer size of the group, however, meant this process took two to three hours, and tensions began to rise. People at the back couldn't hear what was being said, others asked when the workshop was 'really going to start', questioning the way it had been advertised, refusing to participate. This tension was telling. This willing by some participants for the workshop to 'just hurry up and begin' was reflective more broadly of the expectant atmosphere of the programme's start, full of anticipation of something undefined. For many, the move to Beirut for an extended period of time had been a significant venture, full of change. Once here, the question was begged, 'Is this it?' By accident, the workshop captured something many of us experienced in these first few weeks – a sense of being in the back row, unable to catch every word: of missing out on something uncertain.

Though posited rhetorically as a school, it felt like neither teachers, students nor the institution really knew what was happening at this stage. This period felt amorphous, and I sought work outside of the programme to supplement my desire to be busy. Part of the problem was that I didn't feel part of something tidy, or tangible; the group was large and unwieldy. Ashkal Alwan runs a broad programme of excellent, and well-attended public events, many of which were indistinguishable from those rendered ostensibly private by the requirement of registration in the programme. This didn't matter greatly, but it contributed to a sense of wafting in a sea of people. I think at these early stages we craved greater structure, especially those among the international crowd who (unlike local Lebanese participants) did not have jobs or other commitments in the city. Toufic is a dedicated but somewhat distanced professor, available for intense and stimulating tutorials, but positioned firmly behind his desk each seminar. Vidokle meanwhile flies in and out from New York, a semi-phantom presence, though a warm one – holding parties, doing performance-readings, opening his flat to participants who need somewhere to stay when he is abroad. He has just recently initiated a group exhibition project for the final chapter.

But the sense of willing things to 'hurry up and start' was an illusion, because what was happening – in between the Adam Curtis film screenings (Ashkal Alwan hosted his exhibition The Desperate Edge of Now in November/December), Toufic's esoteric seminars, and lectures from visiting practitioners, in between the official calendar's schedule – was that a group of people got to know each other. This sounds simple, but it is not to be understated. A group that arrived as an uncoordinated mass, cliquing into sub-hubs formed vaguely along linguistic and national lines, began to coalesce. We swapped numbers on our basic pay-as-you-go phones, arranged impromptu trips to the beach, found flat-shares, went for walks, hosted dinners, danced in bars. People floated in and out of the Ashkal space, but traffic was common. Conversations buzzed from different corners, studios were occupied. Artists were behind laptops rather than throwing around paint, but watermelon was shared heartily, and Almaza the cat was played with on sofas as the sun slid lazily down the large windows. Was this a productive state of being? Probably not in a 'professional' sense – I'm not sure anyone made much in this time – but in fact we were engaging in precisely the kind of work that this programme required at its outset. We were building a network, establishing points of connection, and identifying sites absent of it; making friends.

And at a certain point things began to coalesce. In an inarticulable way, the beers, the coffees, the lounging around on sofas, the days at the sea or walking in Hamra, pushed the programme to a critical tipping point. The group had massed an intimacy, a comfort, a confidence. We had worked without working to a point where generative interaction and discussion was possible. The talk of independent explorations, of collaborative endeavours – for a while floated as hopeful but unrealized buzzphrases – began to take form. Two participants developed an interactive performance; others collaborated on an archival project; organized film screenings and open crits; there was a poetry reading at another gallery; Vidokle hosted a dinner with an artist-chef from Ireland; three curators organized a group exhibition. By December, it felt as though Irit Rogoff's words were finding voice here: 'At its best, education forms collectivities – many fleeting collectivities that ebb and flow, converge and fall apart. These are small ontological communities propelled by desire and curiosity, cemented together by the kind of empowerment that comes from intellectual challenge.'[4]

We had indeed become a community of sorts, and yet I'm not sure intellectual challenge was what cemented us together. Beyond the 'workshops', 'seminars' and 'talks' – terms used, in practice, interchangeably by Ashkal Alwan and rarely deviating from a lecture-plus-Q&A format – is the educational element of this 'school' important? How much does this programme's approach represent issues around education – specifically, the introduction of pedagogic models that refute traditional educational paradigms?[5]

In a sense, this year's HWP is radical. It provides an important open space for work, a community in which one might become embedded and educated, all for free. Particularly for those locally, or from within the region, the programme counters a lack of infrastructure for art education. It does so while borrowing from established models of liberal pedagogy, and arguably falls prey to Rogoff's critiques on this score. She writes about the emergence of 'pedagogical aesthetics', characterized by 'a table in the middle of the room, a set of empty bookshelves, a growing archive of assembled bits and pieces, a classroom or lecture scenario,'[6] none of which are bad, but which have the potential to prioritize form over content. Rogoff argues that 'the promise of a conversation ha[s] taken away the burden to rethink and dislodge'[7] (my emphasis). Is the existence of the HWP events more important than what comes of them? As Rogoff continues:

The art world became the site of extensive talking – talking emerged as a practice, as a mode of gathering … But did we put any value on what was actually being said? Or, did we privilege the coming-together of people in space and trust that formats and substances would emerge from these?

As Tom Holert also asserts, 'Within the art world today, the discursive formats of the extended library-cum-seminar-cum-workshop-cum-symposium-cum-exhibition have become preeminent modes of address and forms of knowledge production.'[9] Is this year's HWP all format? Indeed, were those early HWPs – with limited numbers, full-time commitment, structured teacher-student relationships – more successful? More productive?

Perhaps HWP 2013–14 should have attempted something far more radical than it has – to reconcile openness as a structuring principle with rigour and high expectations as a pedagogical position. One that allows for participants to be flexible with time, that expands to hold a large group, but which also expects something specific from everyone – self-determined goals that fit within each participant's financial and temporal means – which demands output, and creates avenues for it. This, however, would also 'require that we break somewhat with an equating logic that claims that process-based work and open-ended experimentation creates the speculation, unpredictability, self-organization, and criticality that characterize the understanding of education within the art world.'[10]

This logic has generated a plethora of alternative models for art pedagogy akin to the Home Workspace Program 2013–14. Open School East is a study programme and communal space for 12 'associate artists' in London. Like the HWP, the programme supports artists 'through studio provision, tuition from international and local practitioners, theorists and curators, and the production of locally focused projects. Free to attend … the study programme is conceived as a year-long, partially self-directed residency.'[11] Islington Mill Art Academy in Salford, Fairfield International, and IF (this University is free), are all similar projects in the UK – dedicated to the facilitation of high-quality, independent arts and humanities educations at no cost to the individual. A central facet of the identity of these initiatives is their relationship to the physical space they occupy and open up to others. At Ashkal Alwan, as Tohmé testifies, 'The space gives us a physicality and we know that physicality affects practice … a way of bringing together many different disciplines into a lab of sorts or an incubator.'[12] However, with the proliferation of online networks of communication, webspace is being increasingly harnessed in the service of offline learning.

Sean Dockray's The Public School best explains itself as 'a school with no curriculum'.[13] Classes are proposed by the public online (I want to learn/teach this) and then people have the opportunity to sign up for them. Once enough have expressed interest, the school finds a teacher and the class is offered to those signed up. The school is essentially reducible to a website, yet it exists the world over in the form of hundreds of groups of disparate individuals united via shared interests. Their website currently advertises classes in contemporary art and politics, conversational Spanish, Dante's Divine Comedy and Jungian psychoanalytics, to name but a few. Meanwhile, The School of Global Art, set up by London collective Lucky PDF, hosts a website bursting with ironic rhetoric and pseudo-naïve Powerpoint iconography, but purports to have similar intentions. 'School of Global Art provides a unique mix of online always-on resources with a real-world network of experts.'[14] Their application form includes questions such as, 'Amount spent on education to date?', intimating the concerns that drive the creation of such programmes in the Western world, where rising tuition costs make continued arts education difficult for many, and legal developments such as the Bologna Process render their value increasingly unidentifiable and subject to institutional nullification. Sam Thorne describes 'escalating tuition fees, cuts to university budgets' and 'the creeping neoliberalization of education at large', as natural fuel for the fire of this debate: 'What's obvious is that many are eager for an art school today to be self-determined, flexible, small-scale and cheap or free to attend.'[15]

While websites such as these make education potentially placeless, the fact is that all of the schools and initiatives cited above originate in the USA and UK, often in direct reponse to the marketization of higher education and a lack of arts funding, driven partly by economic crisis. It is important to recognize that the reclamation of spaces (real or virtual) for self-determined education in the West arises out of pre-established means of instantaneous communication and available models for self-organized alternativity. How are schools and programmes of this kind operating elsewhere in the world, especially in regions without the same infrastructure, communication systems, or histories of non-conventional approaches to pedagogy, such as the Middle East and North Africa?

MASS Alexandria is an art school run by Egyptian artist Wael Shawky, who brings together 12 to 20 students for each programme, through an open call, to 'work with them individually and as a group for seven months, where the students are static and the 'professors' change.'[16] MASS exists 'to complement the practical, craft-based skills offered by the university with studies of theory and methodologies to enable new channels of thinking'.[17] Indeed, the problem here is not necessarily of arts education becoming enslaved to market concerns, contemporary buzzwords (see Art&Education's daily newsletters for the thousands of Curating/Cultural Management/Contemporary Practice courses seeking applicants), and rising University costs. Rather, it is one of infrastructure and resources. MASS, continues Shawky, 'is certainly a response to a lack of art education schemes in Alexandria, as well as more generally in Egypt.'[18]

Then you have Sada, an Iraqi initiative run by Rijin Sahakian described as a 'non-profit project supporting new and emerging arts practices through education initiatives in Iraq and public programmes internationally'.[19] While university arts programmes remain popular in Iraq, their traditional academic approach often leaves students without access to critical feedback, contemporary context and wider art historical knowledge. A lack of contemporary resources in Arabic, unstable Internet access and the web's linguistic bias mean students do not grow up in the same environment, characterized by connectivity (not to mention safety from war), as their European peers.

Another initiative is The Creative Space in Beirut, a free school that runs a three-year course in fashion design, sponsored by Parsons the New School for Design and international fashion houses. The idea, again, is to combat an absence of training opportunities for local students in this discipline, and the school particularly welcomes applications from refugees and those who live in Lebanon's camps. The Silent University, initiated by Ahmet Ögüt, celebrates and harnesses the skills of asylum seekers and refugees, who are often highly trained but prevented from practicing their professions in host countries. It operates as 'an autonomous knowledge exchange platform [which] aims to address and reactivate the knowledge of the participants and make the exchange process mutually beneficial by inventing alternative currencies, in place of money or free voluntary service.'[20]

These programmes owe a debt to Tania Bruguera's Cátedra Arte de Conducta, an art project and 'space for alternative training to the system of art studies in contemporary Cuban society'[21] which ran from 2002 until 2009. Its curriculum focussed on Behaviour Art and politically-oriented action, but was free and open to a wide audience. Like those above, it originated in a society without established arts infrastructure, and created specialized archives and a library collection that countered absence of artistic resources within Cuba. The project was influential as a model for other programmes sitting at the intersection of artistic education and social concern.

Each of these schools greatly resemble their western cousins – the emphasis is on free participation, space for skills acquisition, open conversation, self-development – and yet they arise in response to quite different problems. Not intended to highlight and resist the pernicious reduction of education to demands of a market, or use the Internet for global connection, these non-western initiatives counter an absence or insufficiency in their society, and use the Internet to broaden their artists' horizons. They are characterized, therefore, alongside the excellent work they do, by an embeddedness in their local context. This is not true uniquely of the Middle East, as Bruguera's work suggests; SOMA in Mexico City and Tranzit, a network operating in eastern Europe,[22] are two other examples of programmes that work to combat a lack of local infrastructure in sub-altern contexts, as well as promoting free spaces that 'encourage dialogue, collaboration and even confrontation'[23] and 'act translocally, i.e. in constant dialectics between local and global cultural narratives'.[24]

In thinking about the above examples of pedagogical initiatives, Ashkal Alwan is particularly interesting in the context of the tension between local and global concerns, which is evident in its demographics. As described, this year's Home Workspace Program is considerably populated with European practitioners who, perhaps inevitably, play out particular relationships with the region and Beirut. Our presence in HWP is a consequence of the same knowledge-based, artistic economies that have prompted the alternative schools described earlier – economies that allow us to freelance, take time off, travel and win funding for our time in Lebanon. In that November workshop with Wood, full of introductions and explanations for why we had come, many participants expressed a desire to 'escape' the art scene of their origins. And yet, Ashkal Alwan's position as an influential player in global dialogue has precipitated conversations and visiting practitioners that reflect predominant Western discourse as we recognize it. What impact does this have on the relationship HWP is forging with its local community?

Local artists, curators and writers are certainly playing a big part in the programme, and travel from all over Lebanon to participate. This is extremely exciting, and much of the richness of this year's Home Workspace derives from the hybrid interaction between international individuals from across the world, for whom Beirut is new, and those who live and work in Lebanon. Different generations and levels of art-world experience intersect these national lines too, with productive consequences. There is little-to-no state funding for art in Lebanon, and few opportunities for free debate and work with some of the region (and the world's) most eminent and inspiring thinkers. Ashkal Alwan provides this, as well as other, vital, resources that cost nothing to use. And yet, the language of the Home Workspace Program is English, not Arabic. Though the HWP team does its best to schedule most lectures for the evenings, plenty of workshops and events happen within working hours, and often prevent local Lebanese participants (who work, or have family commitments) from taking full advantage of the programme.

In fact, the recreational atmosphere I described at the start, which facilitated the friendship process, was one undertaken predominantly by the international crowd who came specifically for the programme. Unshackled by domestic concerns, this group was free to simply reside in the space, available for the daily interaction that catalyses collaborative endeavours and enhances friendships. There is perhaps an unfortunate irony here: the Home Workspace Program fulfils a need for infrastructural resources for its local community, and yet its set-up makes full involvement within it possible most easily for participants from abroad. Kaelen Wilson-Goldie astutely articulates this, perceiving in Ashkal Alwan:

The tensions running through any organization that tries to balance the need for privacy – for spaces where experimentation is encouraged and failure is forgiven – and the desire for public engagement, particularly in a place where meaningful opportunities to participate in political life are few and far between.[25]

Christine Tohmé speaks passionately and inspiringly about her commitment to civic engagement through Ashkal Alwan (whose initiatives and programmes, it must not be forgotten, extend beyond HWP). 'I am interested in creating civic pockets,' she says, 'we have lost our public spaces today because the control over such spaces is unfortunately decided by the victor … I am interested in these small pockets that exist outside of the system…where you find a seepage between the artistic and the civic.'[26] Is the Home Workspace Program, seemingly dominated this year by its international students, a site of seepage between artistic and civic concerns? No longer does Ashkal work among a quotidian audience on the corniche or in parks. Even within the beautiful warehouse space, perhaps greater civic engagement would have been accomplished by an Arabic-speaking cohort, by prioritizing Middle Eastern participants.

Yet, such prioritization would have missed Tohmé's point. Dieter Lesage writes staunchly in defence of this kind of international mobility in the context of the Bologna Process:

Counter to the ongoing backlash … I think it is important to defend mobility, not as the obligation, but as the freedom to move. The hypermobile actors within the field of expanded academia … should endorse this aim of the Bologna Process – unless they would want to consider the advantages of describing academies as closed, regionally oriented institutions operating in contrast to the open and globally oriented institutions of expanded academia.[27]

Indeed, the problem Ashkal grapples with – of uniting a desire for diverse global participation with that for increased local agency – is one that Tohmé and her team interrogate daily, and one that distinguishes Ashkal Alwan from the other examples explored here. For Tohmé, HWP is:

a very important project not only for Beirut, Lebanon or the Arab World, its intention is to take participants from all over the world based on merit. This is a model that is very important and we really want it to be about openness and fluidity, which is why we insist it is not only for participants from the Arab world. This is a political position.[28]

These questions will no doubt resonate throughout the programme for both participants and for Ashkal Alwan itself, and remain important issues for years to come. The plan for the Home Workspace Program 2014–15 has recently been announced, and the format will return to its earlier set-up, with a limited cohort and year-long commitment. This is not to say that this experimental year has not been a success. For us as participants I think I speak for the vast majority when I say that it has been hugely stimulating thus far. Almost every person who has come for a short amount of time has returned again, or made plans to come back. This is a result, undoubtedly, of the calibre of the curriculum (everyone is eagerly anticipating Hito Steyerl's arrival in April, and already missing Anselm Franke) but is also crucially thanks to the simple phenomenon I described at the start. The unstructured atmosphere, at first a disorienting state, has given way to a liberating ease that characterizes the group, and constitutes an organic structure of its own.

As Tohmé articulates, 'I think that you give people possibilities and in that moment you give them the means to take these possibilities and concentrate and facilitate further ideas inside of an environment.'[29] HWP 2013–14 is not about creating infrastructure or countering neoliberalization, but about space for new relationships, for incubating friendships and – by extension – connections, questions, ideas and answers. Earlier I asked, what comes from each seminar? What knowledge is produced? These are not really answerable, and not necessarily important now. Work is being done in the spaces between such questions. New faces emerge, old friends recede, and the work continues.

[1] Julieta Aranda et al., 'Editorial – "Pieces of the Planet" Issue One,' e-flux 48 (2013): 2.

[2] A Chapter Zero was formed by those participants already in Beirut by September. Ibid.

[3] See data visualization at the end of the article, based on information gathered on 8 November 2013

[4] Irit Rogoff, 'Turning,' e-flux 0 (2008).

[5] 'Home Workspace: A Conversation between Christine Tohme and Anthony Downey,' Ibraaz, 2 May 2012.

[6] Rogoff, 'Turning,' op cit.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Tom Holert, 'Art in the Knowledge-based Polis,' e-flux 3 (2009).

[10] Rogoff, 'Turning,' op cit.

[12] 'Home Workspace,' op cit.

[13] See: thepublicschool.org

[15] Sam Thorne, 'New Schools,' Frieze 149 (2012).

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.

[22] Specifically in Austria, Hungary, Slovakia and the Czech Republic.

[25] Kaelen Wilson-Goldie, 'Public Education,' Art Forum (2012).

[26] 'Home Workspace,' op cit.

[27] Dieter Lesage, 'The Academy is Back: On Education, the Bologna Process, and the Doctorate in the Arts,' e-flux 4 (2009).

[28] 'Home Workspace,' op cit.

[29] Ibid.