Interviews

An Open Methodology

Ahmed Nagy in conversation with Mai Elwakil

I remember seeing the work of Egyptian artist Ahmed Nagy for the first time in 2010. From one of the back galleries of Cairo's Palace of the Arts roared the sound of a TV host presenting a game show in Ultimate Computing – The Holy Zero (2010), a video projection of a recognizable TV program that aired every night with an often seductively dressed presenter asking viewers to call in and answer the most absurd of questions. This was contrasted by another video projection: footage from science shows. Indeed, over the past decade, Nagy has become known in Egypt for work that reflects on scientific knowledge and the process of its creation alongside the workings of mass media. But his approach today could not be further from Ultimate Computing – The Holy Zero. In this interview, Nagy explains why.

Mai Elwakil: You have just returned from Denmark, where you took part in the Wavy Banners project organized by the Cultural Collaboration in Mid and West Jutland. Could you talk about this project?

Ahmed Nagy: Well, I was one of 53 artists invited to design banners for the cultural festival 'The Wave' which took part from 17 August to 19 October 2013. We were asked to respond to the theme of the wave since the peninsula overlooks the Atlantic Ocean. The banners were then hung on the streets of Humlum, Soender Nissum, Noerre Snede and Vorgod-Barde as part of a touring exhibition. I was also asked to present my work in the symposium held in parallel to this exhibition.

MW: This is the first time you produced work for a public space, is it not?

AN: Yes. And the curators wanted to present me with this challenge and opportunity, something I had never done before. In fact, I was never interested in exhibiting in public spaces or making art for the 'public'.

MW: So what inspired you to develop this project?

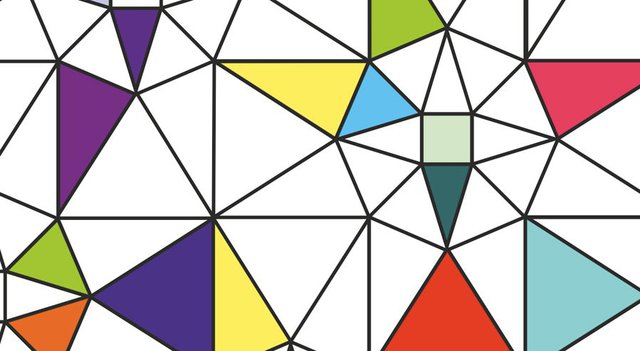

AN: I am generally not interested in making art inspired by historical places. What excited me about this project, however, was that the curators allowed us to interpret the idea of the wave freely – either in philosophical or humanitarian terms – as an actual sea wave, or even as a metaphor for human relations. So I was able to play around with it according to my interests. I decided to approach it geometrically, using triangles as the primary motif for the banner design. Connecting the triangles resulted in an eight-point star, which hints at the region I come from, and in turn, connecting the stars created an infinite possibility of shapes. To colour the triangles, I randomly used all 256 colours on the palette, which also reflects the arbitrary nature of waves. So, my banner became a wave of infinite shapes that all came from the same origin.

The banner design reflects how everything is connected in real life. Indeed, politics is reflected in art as much as science and economics. Look at the art that has been produced in Egypt since the revolution – much of it is related to political developments. Artists produce and present their work within this context; collectors buy them, researchers analyse them, and more production and exhibition opportunities arise. From my perspective, I can see waves bringing forth many things, even if these 'things' are subtle or even not visible at first.

MW: Why did you want to present the banner in a public space at this moment in time and in this particular region in Denmark, as opposed to previous opportunities you might have had in Egypt over the past two and a half years?

AN: Honestly speaking, the art projects I had recently seen in Egypt have not encouraged me to create this kind of public art. One thing that particularly troubled me when it came to such production was that artists were presenting street or mural art as graffiti. Drawing on walls in daylight with the support of institutions is more of a decorative or commemorative gesture. But, saying that, I also think that much of my previous work, such as Ultimate Computing – The Holy Zero, would not be enjoyable to the average person.

MW: Why do you feel that way?

AN: It is the final form it takes. I do not use bright colours or talk about feelings, beauty or anything romantic. The concept dictates how I translate it into my artwork. If you look at the two works I produced last year, The Fake is Vogue and Each context has at least an agent (both 2012), you would find them more suitable for a gallery setting and an art audience. Each context has at least an agent is part of the When We Are Successful, and We Will Be series that I worked on for three years (2010-2013). The series includes four works, which were all inspired by a speech George W. Bush Sr. gave on January 29th 1991 – the night of the US military strike in Iraq. He said:

This is an historic moment. We have in this past year made great progress in ending the long era of conflict and cold war. We have before us the opportunity to forge for ourselves and for future generations a new world order – a world where the rule of law, not the law of the jungle, governs the conduct of nations. When we are successful – and we will be – we have a real chance at this new world order, an order in which a credible United Nations can use its peacekeeping role to fulfill the promise and vision of the U.N.'s founders.[1]

I exhibited Each context has at least an agent, which is the third work in this series, with The Fake is Vogue in September 2012 in the Intersecting Lines group exhibition set in Cairo's Al-Hanager Art Centre. The show was meant to reflect on everyday life in Egypt since the revolution. And I responded to this theme with a work about interpretation, a topic I had started thinking about in 2012 while following the news. There was a lot of confusion. My friends and I would sit and discuss the news; each of us interpreting it based on what we wanted to believe. For example, we knew people had died; some would say the police killed them, others would accuse hired thugs, and some would go as far as to say that people had taken their own lives.

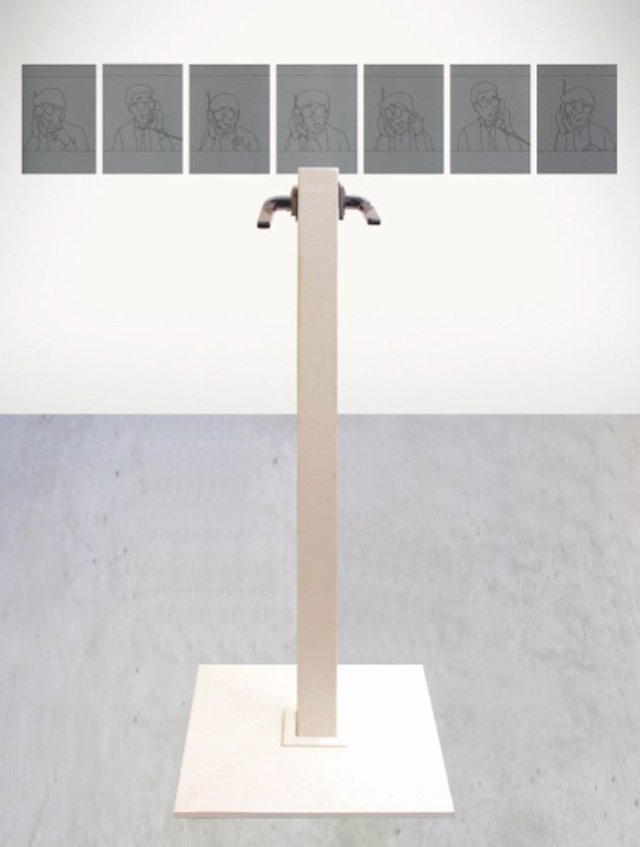

For the Intersecting Lines show, I decided to approach this idea subtly, and drew a very simple storyboard of two people talking on the phone, titling it Each context has at least an agent. There were no speech bubbles and I completely de-contextualized the characters. I exhibited this with a sculpture, as I foresaw the audience standing in front of the storyboard. I imagined there being a knob, attached to an abstract object instead of a door, thinking that this would open up people's imaginations or allow them to interpret the work however they wanted. The sculpture was entitled The Fake is Vogue, which is also the title of a text I contributed to the PhotoCairo 5 arts festival in 2012. The text focuses on references to the revolution and politics in art, and how didactic both ideas of revolution and politics can be, depending on the artist's approach.

MW: What about the three other works inspired by Bush's statement?

AN: There is A Statement of Complex Relationship (Artificial Aesthetics) (2013), which is a selection of photographs of decorative objects found in the average Egyptian home. These objects have an artificial sense of beauty. They are imported from China and their aesthetics are somewhat Roman. I was visiting a friend and found that his mother had decorated the entire house with these objects, constructing compositions from a small statue she got in a baby shower, a ribbon from a chocolate wrapper, a child's necklace and a plastic rose. I asked her why she put these items together, and her response was: 'Don't you think they're beautiful?' It was that simple to her.

MW: How do you frame this work within the overall theme of the series?

AN: Artificial Aesthetics is related to Bush's statement because it reflects the changing world economic order he spoke of. China, for example, produces objects following the aesthetics of Roman art in Italy to be sold in Egypt, because people here aspire to be like Italy. So, Artificial Aesthetics is a very simple work, and is related to the context in which Bush's statement was said. But in Performative Sentences (2012), shown in the second edition of Cairo Documenta at the Viennoise Hotel, I turned Bush's statement into a question. I asked people when they see themselves succeeding and edited their responses into a text. The work became a collection of people's visions of success.

MW: Were the responses surprising?

AN: Yes. I found that most of the answers were contrary to the original context of the statement. When Bush made that statement, it was a declaration of war. He knew he would succeed because he had prepared for the war and its aftermath. It is a 'physical sentence' based on real action. But most of the respondents I asked this question to did not do much to reach their goals. They said they wanted to succeed but kept coming up with excuses, which they believed were holding them back. Whereas in reality, the people were not doing anything. So their responses become more of 'mental actions' in the sense philosopher John L. Austin discussed in his book How to do things with words.

One religiously conservative respondent even said that he would succeed when he became God – agency went against his beliefs. And I chose to end my text with that statement so readers would progress until they reached a point where there is nothing at all related to reality.

MW: Could you talk about the film you have been working on through the 2012 platform I + I + I, which was supported and funded by the Danish Egyptian Dialogue Institute (DEDI)?

AN: I am generally interested in analysing the way mass media affects people and their consumption patterns. You remember Ultimate Computing – The Holy Zero and the two projects I produced with artist Mahmoud Hallwy: Two Taia3 (2009) and Interview (2010)? In these projects I was interested in analysing the image of consumption through television and how it influences people's cultural and social lives. This interrelatedness, which is subtle in the Wavy banners project, is obvious in these works and in Somewhere/Everywhere (2010). The latter, which is the first work in the When We Are Successful, and We Will Be, was a collection of profile pictures women set up on Facebook. The photos are often very seductive, reflecting a parallel life they want to live as pop stars.

Such relationships are an underlying theme in my work. But with the new film, Behind the Scene (The Vision) (2012-present), I am using a different methodology and language. The film is based on a three-week workshop with a group of artists, writers, architects, theatre practitioners and curators, who are all engaged in critical practices within the contemporary art scene. I + I + I required that we discuss the processes we use to develop our work and collectively produce a work similar to Jean-Luc Godard's Sympathy for the Devil (1968), also known as One plus one.

MW: Similar in what way?

AN: It is meant to be similar in terms of the structure of the scenes. Godard's film documents the production of The Rolling Stones' song, Sympathy for the Devil. Its approach to combining elements and editing them into the plot is unique. The workshop encouraged us to investigate the processes of art and knowledge production, and to mediate and combine our visions using the same experimental framework of Sympathy for the Devil. In turn, I have been working on Behind the Scene (The Vision) as a set of scenes where performers read different scripts I had collected while seated in dark rooms, lit by fluorescent-coloured lighting. There were seven rooms lit with the seven colours of the spectrum, which eventually formed white light. Artist Sherif al-Azma shot the film.

MW: This work relates to ideas you were previously working on, too, is that right?

AN: Definitely. This film still reflects my interest in the subtle relationships between things, with all seven colours composing white light. It also uses scientific knowledge. This is what is behind the scene. I am focusing on the components of things thatare very presents and clear to me, yet that cannot always be seen. But this film is much subtler than The Holy Zero or Somewhere/Everywhere. Here, I am moving away from trying to directly translate the Media. I am now just creating a structure for people to imagine and develop their own interpretations.

MW: You followed a similarly subtle methodology with the Wavy Banners project; your banner could even be seen as a decorative item.

AN: That was intentional. I wanted to create a banner based on my own process of personal research. At the same time, it looks inviting and pleasant to everyone. I became more interested in opening things up to the audience about a year ago. I think this methodology allows me to do what I want while maintaining the form and language of an artwork. I do not think that my art has to be obviously related to the personal, social, political or religious experiences that inspired it as is the case of Here/Everywhere. My text-based works might also be inaccessible to gallery visitors. But when audiences see an artwork that is somewhat similar in nature to their expectations, they might try harder to read into it.

MW: This change in your methodology – balancing your process with the artwork – is also clear in Every context has an agent. In your earlier works, you used to clearly insert texts and theories to direct viewers. How has this change come about?

AN: Recently, I felt that I wanted to move away from discussing things in any direct way. My interest is more in the process and ideas behind my work and the research I conduct on the underlying connections between things. This is what I want to focus on and most of the artworks I like have a lot of research behind them. Even if that research does not entirely reach the viewer, it is still there. It presents a new proposition and reflects the artist's individuality in ways that are not personal. Still, the public can relate to the artwork.

Previously, I was interested in trying to translate what I was going through in my artwork, and though I still believe translation is important, I am now experimenting with different ways of doing that. Over the past year, I have been changing the language I use so it becomes more simple and abstract. In fact, this is also why I was not so interested in public space before. I felt that if I produced a work for public space with the same methodologies I had used in the past, it would be unfair to the public, as it would have been very complex. So I am changing my language, finding new ways to say what I want to say and to avoid superficial translation. I spent a whole year producing nothing. I just watched everything that happened around me: the artwork being produced, the institutions opening up, all the developments happening in relation to the revolution in Egypt. I started reading my work within this context and realized how these events as well as economics dominate the art scene and the artwork being produced. It was like post-9/11 all over again, when everyone worked on issues related to Islam so as to get exhibited abroad, only this time the focus is on the protest movement. I wanted to distance myself from all of this.

When I was in Denmark, a housewife told an artist whose work was directly linked to the living conditions in his country that she did not see the artistic language in his work. She said it was similar to what she sees in the media and said that she feels like such works underestimate both audience and artists. This woman knits crochet. She learned it from her mother, but has been making new and innovative knots. It does not matter if other people learn it. She really experiments with her knitting. I think that the way you translate your ideas and how you are honest with yourself are what makes a work have impact. This is what has made me focus more on the concept and what has directed me in terms of the language or forms I use. I believe that art has its own language.

MW: And you feel that this was not achieved in your previous work?

AN: Not enough. Not in terms of the way of thinking and the language I used. Some of my work was built on presenting the consumerist society in some way. And this is what I am now trying to move away from – anything that can be easily bracketed or used to pigeonhole artists from the region and which can be read in relation to this specific context. Things like politics and religion. I think there are other ways to address these themes. I see a lot of works that do not deal with the naive elements of these topics, such as works by Sherif al-Azma, Hassan Khan, Ahmed Badry, Basim Magdy and recently Mohamed Abdelkarim. Their works are layered and avoid any literal translation of such 'hot topics'. This is also related to the artist's background, references, and how the artist reads into events.

MW: You mention references as a key element in informing an artist's practice and you constantly read about science, technology, medicine, philosophy and the like. But you also completed a diploma in painting and art criticism right after graduation. Why were you interested in that at the time?

AN: I started as a painter and felt that criticism would move me closer to the reading of art. My professor, Dr. Emad Abu Zeid, asked me to research ten artists from the 1980s and collect their work from the archives of major Egyptian newspapers. I researched artists including Mohamed Abla, Reda Abdel Salam, and Adel al-Siwi for a year. And I began reading about how they presented their work, how they translated it, and how one artist's work complemented another's. This was my entry point to reading the artwork through the artists. I found that many critics interpreted the artwork and presented it in relation to a perceived Egyptian identity. They would say, for instance, that this cat is there because it is a symbol of ancient Egypt, whereas the artist might have had very different intentions and interests. This made me think about criticism, how academics think about art, and what contemporary artists think. I found that things are much more flexible and include elements that could be simpler or more complex than what we were taught at art school. This is what made me think of using different artistic media and I started learning about video art.

MW: And this was a way to escape these frameworks or narrow readings into artworks?

AN: Yes, and also to try and translate my ideas in a simpler way. Like, if I wanted to talk about freedom, I would not need to paint a person flying with his arms wide open. I produced my first video in 2007, 2 layers II, which was shown at the Istanbul Biennial that year. The idea was very simple, but the reception encouraged me to continue experimenting with new forms and languages. I had filmed the gardener at our school as he dug every day, looking for something in the earth. Then I noticed that people in Cairo were also trying to generate some income by searching for opportunities. I combined the footage of the two things with quotes by Aristotle on the social contract. It was a very simple work. I was excited by these new possibilities.

MW: And you have been trying to share this approach with others through the platform you founded, Space for Contemporary Art and Cultural Development, right?

AN: Yes. I founded the space so we could discuss different methodologies with emerging artists and work with them on developing their own unique artistic voices and languages. Many emerging artists use a personal, social or political language to translate their ideas, rather than an artistic one. So I started with organic workshops for mentorship that were formalized in collaboration with the Contemporary Image Collective. As we developed the mentorship program further, artists Doa Aly and Osama Dawod were invited to hold critique sessions with enrolled emerging artists. I could see the developments in the artists' work clearly in the resulting exhibition, The Parenthesis Show hosted by the CiC in February 2012. And in July of that year, another group of artists I worked with exhibited in The Pick 5. I followed a similar mentoring process only this time the Space ofr Contemporary Art and Cultural Development collaborated wit the Townhouse Gallery in Cairo to develop the ideas of emerging artists.

I want to continue with this approach. I hope the next workshop will involve emerging artists from both Egypt and abroad, so they can exchange their perspectives. That would be very useful for both groups. I am generally interested in making the workshops focus on developing the artists' ways of thinking and language, rather than focusing on technical aspects like video editing. I believe this will have a stronger impact, allowing audiences to read the ideas through the artwork, rather than through an explanatory text.

MW: What are you working on now?

AN: My current project is entitled Sympathy with Hysteria. It also tackles the underlying relationships between things. But this came about because I am constantly questioning what I think and believe in. For example, I started by asking myself if I believe anything I hear from scientists since it seems that the public believes all stated scientific findings. This led me to think about the nature of science; is it becoming a new kind of religion? And how do art, science and religion come together? So it is like a continuous questioning of all human experiences that blends together like a helicopter rotor. Thinking about his, I searched for an image of a rotor and began grading it with the colours of hysteria. I have been researching hysteria and have found that – scientifically – it does have colours: a colour reel for hysteria resulting from love, hope, pain and so on. I am still unsure about the final form this work will take, but I want to create my own process.

Ahmad Nagy is an artist based in Cairo, and is the founder and director of the Space for Contemporary Art and Cultural Development. Nagy co-curated The Pick 5 (2012), an annual exhibition initiated by the Townhouse Gallery, which highlights the work of promising art students and early career artists. He was also the initiator and art director of The Parentheses Show (2012), a workshop and exhibition for mentoring young artistic talents supported by the Contemporary Image Collective in Cairo. Nagy completed his BFA in 2002, as well as a diploma in criticism and painting in 2004 from Helwan University. His practice focuses on building subjective interpretations of multiple contexts by analysing various forms of cultural consumption with a focus on the impact of consumerism on art and the media. Nagy is currently a resident artist of the Pro-Helvetia 2013 artist-in-residency programme. He also took part in Progr Festival in Switzerland (2013); Wavy Banners (2013), a public exhibition and international symposium in Denmark; The Times Are Changing: What Will Art Do About It? (2012), a two-day symposium on the concept of change and its relation to art practice, organized by the Alexandria Contemporary Arts Forum; and I + I + I (2012), a collaborative platform for Egyptian and Danish curators, artists, writers and theorists engaged in a critical practice within the contemporary art scene. He also participated in Visiting, organized by the Townhouse Gallery in 2012 - an open-ended, collaborative residency between six artists from the Rijksakademie in the Netherlands and six Cairo-based artists. He took part in Interview (2010) at the Saad Zaghloul Museum in Cairo, and Cairo Documenta (2010-2012), Shopping Malls (2010) curated by the Alexandria Contemporary Arts Forum, Why Not? (2010) at the Palace of the Arts in Cairo, and Invisible Presence, curated by Mashrabia Gallery in 2009. Nagy also exhibited his work at Darat al Funun's Youth Salon in Jordan in 2009, the second Instant Video Festival in France in 2009, the 10th Istanbul Biennale and the 4th Tehran Biennial of Painting. His work is found in Artist Pension Trust / APT Dubai, the Modern Art Museum in Cairo, as well as private collections in Poland, Croatia, the Czech Republic, and Nigeria.