Interviews

After the Biennial

Fulya Erdemci in conversation with Basak Senova

Fulya Erdemci was the curator of the 13th Istanbul Biennial, Anne Ben Barbar Mıyım? or Mom, Am I Barbarian? (14 September–20 October 2013). The theme for the biennial was decided well before the eruption of protests in Turkey, ignited by the planned demolition of Gezi Park on Istanbul's Taksim Square, taking as its thematic focus the idea of public space. It intended to explore the public sphere as a 'matrix', while considering 'the role of art through inquiries into current-day spatial and economic policies, forms of democracy, the concepts of civilization and barbarianism.'[1] In this interview, Erdemci reflects on the outcomes of the biennial retrospectively, taking into account the impact of the Gezi Park protests.

Basak Senova: From your perspective, what impact did the artworks presented in the 13th Istanbul Biennial have? Did they attentively touch the issues – both locally and globally – pertaining to the public sphere?

Fulya Erdemci: Certain art works (including poetry or other forms of literature or film,) have the capacity to create a transformative experience, and open up the possibility of moments of utopia in our daily routines. Activism and art can have the same aim of social change in times of urgency, and they can learn from each other, such as the recent times we have been experiencing. Nevertheless, they have different processes, experiences and impacts, and cannot be evaluated with the same criteria. I believe that each work in the biennial had the capacity to open up the seams of the system to show the possibility of the otherwise. The biennial's power came from bringing the very personal and very public realms together to open up the possibility for collective imagination.

Although I believe that art functions in the symbolic realm, in certain times of urgency – such as those we are going through – it may have an immediate impact. For instance, the Sulukule platform, Networks of Dispossession (2013), Serkan Taycan's Between the Two Seas (2013) (the canal Istanbul project), Wonderland (2013) by Halil Altindere, the Gezi drawings by Christoph Schäfer or Monument to Humanity – Helping Hands (2011–2013) by Wouter Osterholt and Elke Uitentuis were able to create heated public debates.

As I see it, art can open up a space for a transformative experience and has the capacity to foster the construction of new subjectivities, symbolized by the barbarian. Art can create a reflective experience appealing to our emotional intellect. It encourages us to halt and think about what we really need now in the midst of such turmoil (with increasing state violence, detentions and arrests) and other powerful transformations.

The reaction towards the exhibition was quite mixed. Some criticized the exhibition for not having taken place in urban public spaces, which they saw as a sign of giving up, and not reflecting Gezi more directly, also in the exhibition format. Yet for others, the exhibition articulated the questions posed by Gezi, fully deploying the power of art without undermining the resistance movement. I cannot say if people liked it or not but it certainly opened up a long-awaited debate. Although the biennial withdrew from urban public space to private venues, it was through public interest (we had 337,429 visiors in five weeks) that the biennial venues themselves became public spaces that people gathered in.

BS: Could you define the structure of the biennial taking into consideration the artists' input and the inter-dialogue that took place?

FE: Following Walter Benjamin's reading of history, in that you approach the future without losing sight of the past, was a method to mark the temporality of the exhibition. In this sense, I endeavoured to crack open a historical aperture between today and the end of the 1960s and 1970s in terms of social change, urban transformation and artistic practices. The most significant common denominator between these two periods was the quest for 'another world'. These decades also witnessed artists developing new artistic practices that challenged urban transformation and gentrification processes in cities such as Paris, New York and Amsterdam. Therefore, for this exhibition, novel artistic practices from the 60s and 70s were brought together, side by side, with more recent practices, such as Mierle Laderman Ukeles with Amal Kenawy; Gordon Matta-Clark with LaToya Ruby Frazier; and Stephan Willats with Jose Antonio Vega Macotella. Furthermore, through the practices of Academia Ruchu in urban public spaces and specifically Jiří Kovanda's performance Theatre (1976), it became possible to contextualize the current performative protests like Standing Man (2013) by Erdem Gunduz within the art historical backdrop of the 1970s.

Geographically speaking, because of education and governmental policies and support, artists from the USA, England and northern Europe have more possibilities and experiences in the field of art within the public domain. However, when we look at what is problematic in the cities and in the urban public spaces, you can see that in last couple of decades, mostly the southern and the eastern parts of the world appear on the map: Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, Peru, Turkey, Palestine, Lebanon, Iraq, Egypt, Tunisia, and so on. Hence, in order to reflect the geopolitics of the globe at present and anchor time spatially, in the exhibition I privileged certain geographies such as Latin America, North Africa, the Middle East, and Turkey, where the question of the public domain and transformation of cities has been a burning issue for the last couple of decades.

Besides, artistic practices engaged with poetry/literature as well as music and performance were also highlighted in the biennial, as experienced through works such as Castle by Jorge Mendez Blake (2013); Pivot (2013) by Shahzia Sikander;Violent Green (2013) by Lale Muldur, Kaan Karacehennem and Franz Bodelschwingh; 13 Essential Rules for Understanding the World (2011) by Basim Magdy; Co-Action Device: A Study (2013) by Inci Eviner, with the participation of 40 artists, writers, musicians and performers; or Shortening the Long Position (2013) by Goldin+Senneby.

BS: Could you reflect on some of the specific projects you showed that were closely linked with the reasons and the consequences of the Gezi Resistance?

FE: Although I deliberately didn't ask any artists to work on Gezi, a couple of projects were directly related to it, for instance, the visual narratives presented by Christoph Schäfer. He and the Right to the City activists supported the Gezi resistance from the beginning by organizing a series of initiatives in the 'Park Fiction' park, which they themselves rescued a few years ago from being appropriated by the urban regeneration of the Hamburg port area. They even renamed it as 'Gezi Park Fiction' on the night that Gezi Park was forcefully evacuated by the police.

Schäfer visited Istanbul a couple of times to meet with artists and activists much earlier than Gezi. And during the resistance, he joined some gatherings, for instance, the 'Yedikule Bostans' or the 'Earth Tables' protests. Having focused on the city as a collective production place, his drawings of the Gezi resistance, narrate the new coalitions alchemically formed amongst multiple publics such as the Muslims, atheists, anarchists, leftists, nationalists, environmentalists, gay and lesbians and so forth. This was specifically expressed in the depictions of the Earth Tables – a way of protesting just by gathering to have dinner together after the sunset on kilometre-long tables on Istanbul's streets and parks during the Ramadan.

Furthermore, although certain projects such as the Wonderland video by Halil Altindere or the I am the dog that was always here (Loop) (2013), by Annika Erikson, were conceived and realized much earlier than the massive Gezi protests this summer. But, they are very much expressing the major issues and the common sentiments related to ongoing violent urban transformation and gentrification, which triggered the Gezi resistance.

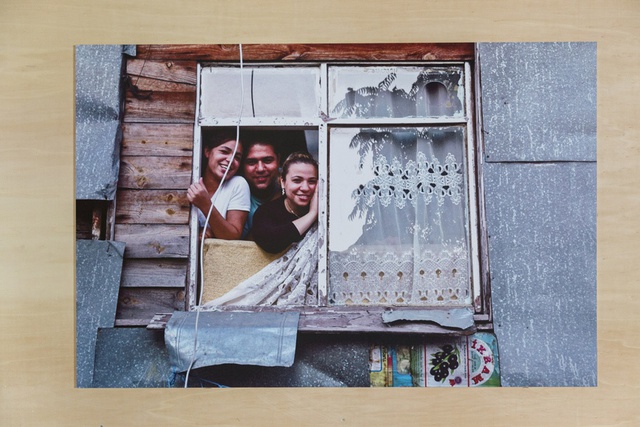

Wonderland focuses on the severe displacement of 300 Roma families due to the gentrification of Sulukule, one of the oldest neighbourhoods and the earliest sites for urban transformation in Istanbul. This very special neighbourhood itself was changed into luxurious residences, constructed by Toki, the governmental organization which functions through public-private partnerships. The video is in the form of a music clip, in which 'Tahribad-i Isyan' (Destruction of Revolt), a hip hop group born and raised in Sulukule, tells the story of their neighbourhood, expressing their anger and protest against inequality. In the film, we follow them through the demolished houses and above the roofs of newly built apartments. Annika Erikson's poetic video, on the other hand, narrates the current process from the eye and experience of a street dog pushed out to the outskirts of the city.

Maider Lopez's project Making Ways (2013) subtly related to the habits of finding collective solutions to the ever-emerging situations or obstacles you often come across in Istanbul. She concentrated on the pedestrian crossing in Karaköy, which is a major transportation hub connecting the Asian side to the European side of the city. She filmed this crossing from an aerial perspective and extracted and highlighted the routes that people take. Additionally, having mined the practice of self-organization through the simple daily actions of Istanbulites, like crossing a street, she created a 'users manual', giving possible instructions on how to cross the roads, such as: 'If unsure, follow a person who appears to be doing it well', 'Taking action is easier when a group is generated', or 'Self-organization creates collective ways'.

Certainly, there were other projects directly related to urban transformation in Istanbul such as Networks of Dispossession, a project by the collective that grew out of Gezi occupation, which consists of network of maps showing the relationships between the actors of urban transformation, the major development companies, the media and the government; or the Sulukule Platform, a grassroots organization started by artists and activists in 2006 to react against the gentrification of the Sulukule neighbourhood and the displacement of the Roma families. Finally, Between the Two Seas by Serkan Taycan aims at creating an awareness around the 'Canal Istanbul', a mega urban transformation project to open up a canal on whose banks two cities with one million residents were planned to be built.

BS: Following the Gezi resistance, you took the decision to withdraw the biennial from urban public spaces. Could you explain the reasons and the consequences of this decision?

FE: The Gezi resistance and the public protests exposed something about the authorities – that they suffer a strong sense of agoraphobia. Instead of listening and responding to the desperate voices on the streets, they preferred to violently repress these voices by police force (thousands of people were permanently injured and seven people died). For this reason, we began to question what it means to realize art projects in urban public spaces with the permission of the same authorities that do not respect their own citizens' freedom of speech. In two forums that we organized in a neighbourhood park at the end of July, we discussed such questions, insights, and possible further actions with artists and activists and other participants.

Drawing on the political theorist Chantal Mouffe, our conceptual framework was that the raison d'être of any art project in the public domain is to open up the conflict and to make it visible and debatable. However, Gezi had already opened up the conflict and made it public. To collaborate with the authorities would have given the authorities the opportunity to regain their lost prestige and legitimacy after Gezi. This would have led to the instrumentalization of art in favour of the authorities. In order not to collaborate with these authorities, we decided to withdraw from public space and continue the discussion in the exhibition venues. In this way, like John Cage's silent composition '4'33"', we aimed to point out presence through absence: by asking the audience to listen to the voices on the streets.

Certainly, this decision was followed by many conceptual, practical and relational complications, including a spatial one. Only at the end of the first week of August, were we able to secure the three additional venues. Thus, we had to renegotiate the projects and re-adapt the plans in a very short time. Thanks to the endless efforts and energy of the biennial team and the artists, it became possible.

However, since we decided to not collaborate with the city authorities, the biennial was not promoted on the billboards in the city (officially the foundation IKSV and the biennial have an ongoing agreement with the municipality to have billboards all around the city). Furthermore, Out of 14 projects that were planned to take place in public space, we lost three projects in total. In all other cases, artists could fit their ideas into the new situation or simply make a completely new project. That is what happened with Elmgreen & Dragset, for instance. They had another project, which was to take place in a specific urban space, however, when we decided to withdraw, they came up with a totally different project in a month, Istanbul Diaries (2013), in which seven men were hired to write their diaries daily in the exhibition space. Tadashi Kawamata, on the other hand, presented the Plan for 'Gecekondu' (2013), which he planned to realize in Taksim on Tarlabasi Boulevard, Halic Dockyard and Karakoy square. The light installation Intensive Care (2013) by Rietveld Landscape, designed to point out to the obscure future of the contested Ataturk Culture Centre at Taksim Square, couldn't be realized. But it was transformed into an interior installation. Their idea was to make the building 'breathe' with certain crisis moments, to mark its precarious 'in between' situation: if the building is still alive or if it is dying. Only during the Gezi occupation, were we able to learn that the building was actually under demolition.

We radically revised the public programme and transformed it into more ground up artist-organized-events, like workshops, walks/tours, talks, performances, music sessions, screenings, and lectures by Networks of Dispossession, Sulukule Platform, Maxim Hourani, Hector Zamora, Hito Steyerl and so on. In the five-week-period of the exhibition, 39 events were realized. As the consequence of this decision along with all the obstacles and drastic developments during the preparation period, some projects were lost and some major changes were made. But if you ask me if I am content with the biennial, yes I am.

Fulya Erdemci is a curator and writer based in Istanbul. Erdemci is the curator of the 13th Istanbul Biennial and was the curator of the 2011 Pavilion of Turkey at the 54th International Art Exhibition, Venice Biennale. She was the Director of SKOR (Stichting Kunst en Openbare Ruimte) Foundation for Art and Public Domain in Amsterdam between June 2008–September 2012. Erdemci was among the first directors of the Istanbul Biennial (1994–2000). She served as the director of Proje 4L in Istanbul (2003–2004) and worked as temporary exhibitions curator at Istanbul Modern (2004–2005). She curated the 'Istanbul' section of the 25th Biennale of São Paulo in 2002, and joined the curatorial team of the 2nd Moscow Contemporary Art Biennial (2007). Erdemci initiated the 'Istanbul Pedestrian Exhibitions' in 2002, the first urban public space exhibition in Turkey and co-curated the second edition in 2005 with Emre Baykal. In 2008, Erdemci co-curated SCAPE, the 5th Biennial of Art in Public Space in Christchurch, New Zealand with Danae Mossman. Erdemci has served on international advisory and selection committees, including 'The International Award for Excellence in Public Art' initiated by the Public Art (China) and Public Art Review (USA), Shanghai, May 2012; the SAHA, Istanbul, 2012; the 12th International Cairo Biennial, Cairo, 2011; and De Appel, Amsterdam's, Curatorial Programme 2010–11 and 2009–10. Erdemci has taught at Bilkent University (1994–1995), Marmara University (1999–2000) and at Istanbul Bilgi University's MA Programme in Visual Communication Design (2001–2007).

[1] Part 1: The public domain has opened up!. Fulya Erdemci in conversation with Basak Senova. First published in Ibraaz, 29 July 2013 www.ibraaz.org.

Part 2: The second part of this interview was commissioned by Contemporary Visual Art+Culture Broadsheet Magazine for the March 2014 issue http://www.cacsa.org.au/?page_id=2833.