Interviews

NOTES FROM THE RESISTANCE

Özgür Uçkan and Vasif Kortun in conversation with Basak Senova

In Turkey, the resistance has continued in many forms. Forums are organised in the parks; people share information and overuse social media; protestors try to organise regardless of the fact that everyone is now on the government's watch lists. In this two part-interview Basak Senova brings some voices and issues which have come into view with the resistance in Turkey from the field of culture. It starts with a conversation with Özgür Uçkan, a leading actor for the legal rights and freedoms on the Internet in Turkey, and continues with a conversation with Director of Research and Programs at SALT, Vasif Kortun discussing his responses to some vital hashtags of the resistance.

PART 1

'To communicate is to be organized.'

Özgür Uçkan in Conversation with Basak Senova

Basak Senova: Turkey has a long history of Internet censorship. Since 2005, it has become more noticeable and accelerated. Starting with a list of 138 keywords banned from Turkish domain names in 2011, Turkey's Information Technologies and Communications Authority (BTK) eventually applied a centralised filtering system in 2012. Nevertheless, up to now, the laws related to the Internet have been intentionally set aside and subject to arbitrary alterations and interpretations. Considering the current authoritarian direction, how do you see the next legal step?

Özgür Uçkan: Up to 2000, the Turkish Criminal Code (art. 159) and Combating Terrorism Law have been used to censor some sites, especially anti-militarist and pro-Kurdish platforms. In 2001, the Supreme Board of Radio and Television (RTUK) Bill (No. 4676) was issued and oppressively regulated Internet publications. But, after 2005, an acceleration in Internet censorship occurred, especially concerning copyright issues. In 2007, the Turkish government enacted Law No. 5651 entitled 'Regulation of Publications on the Internet and Suppression of Crimes Committed by means of Such Publication.' With this law, nearly 30, 000 web sites were blocked. In 2011, the Authority (BTK) issued 'Procedures and Principles on Safe Internet Service' and a state-owned, centralised filtering system became operative.

BS: In this respect, to what extent is public opinion part of setting of these policies?

ÖU: In 2011, nearly 60,000 people protested the mandatory state owned central filtering system in Istanbul and other cities of Turkey simultaneously. The first decision of the authority imposed a mandatory filtering system with four profiles. It contained everybody. But, after these protests, BTK retired its first decision and published a second one. This time, there were only two profiles (child and family) used, and it stayed centralized and state-owned. The system became non-mandatory and they abstained from using words like 'filter' (they changed the word 'filter' with 'safe Internet'). So we could say that the public reaction has an important impact on state policies.

But sometimes public opinion can be manipulated. For example, before enacting Law No. 5651, authorities organised a disinformation campaign. They arrested a lot of people with charges of child pornography. The material, which these people possessed, was not child pornography but classic pornography labelled 'barely teen' (with 18+ models). They used mainstream media to create an impression that child pornography was a very common issue in Turkey. But this was not the case. In the meantime, they enacted the law by presenting it as a special law against child pornography. In reality, the law criminalised not only child pornography but also different content categories (encouragement of and incitement to suicide, facilitation of the use of drugs, provision of substances dangerous to health, obscenity, gambling, and crimes committed against Ataturk). These arrested people were freed a couple of months later except one (a British citizen persecuted by Interpol charged for being part of an international child pornography network), but nobody noticed this. This example offers a real case to study the manipulation of public opinion.

Up to this centralised filtering system, people were not really concerned about Internet censorship because they could easily bypass it (tunnels, DNS management et cetera). This indifference contributed also to legitimate censorship mechanisms. Besides 5651, the Penal Code and Combatting Terrorism Act is used heavily to censor political content on the web. A lot of users were not aware of that, or they accepted it because of disinformation about 'terrorism'.

Public opinion is important to counter censorship, but it may be easily manipulated too. 2011 was the turning point for reactions against Internet censorship. Timely, the big protests chanted: 'Don't touch my Internet'. It was the biggest street action in the world concerning the Internet. Today, public opinion is much more enlightened about censorship and other problematic issues and the authorities has more of a problem to legitimate their efforts in oppressing the Internet.

BS: 'Censorship' has been a unsettling and futile political and social phenomenon in Turkey. How do you frame it in its broad sense?

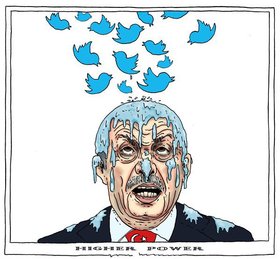

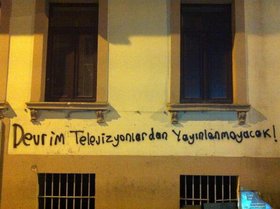

ÖU: Turkey is a habitual criminal of censorship. Censorship as a favourite tool of oppression is deeply rooted in the history of the country. We have one of the worst records of press freedom worldwide. The mainstream media is abominable: heavy censorship and auto-censorship, lots of journalists arrested, corrupt relations with power and so on. The Internet, especially social media and the blogosphere, has become an indispensable and effective alternative to the mainstream in Turkey. The government's perception against the Internet and social media is escalating. Government sees the Internet and social media as public enemy number one, or as a 'curse', and this is comprehensible.

Concerning the Internet, government was always authoritarian in Turkey. This tendency has become more visible in the last years and after the Gezi resistance, the government's perception of the Internet as a threat marks this tendency's zenith. They fear a lot, particularly from social media, because social media's stream is real-time, massive and expands exponentially. Their next step will be to control social media. But censoring selectively is nearly impossible. They can totally block access, but they cannot censor it, not without the cooperation of social media companies. A total shut down is not effective too. It would create economic and politic repercussions against the government. Look at China or Iran; a lot of people keep using social media, despite the blocks. There are so many tactical tools to bypass censorship.

BS: Then what is the government's strategy to control social media?

ÖU: What the Turkish government is doing against the so-called threat of social media is to organise police operations to provoke auto-censorship amongst social media users. They take people, chosen arbitrarily, into custody without a real criminal charge. They are trying to create a regulation to criminalise dissident social media content to legitimate these operations. They spread a lot of rumours about a 'Social Media Criminal Code' to survey public? Reactions, but at the same time, I think they are confused technically. They know very well that with their censorship experience in the past, the people learn fast when it comes to bypassing oppressive technical mechanisms. In this regulation passé, users will use alternative access technics, anonymisation tools and strong encryption. This will be a nightmare for the authorities. At the same time, Turkish authorities use, illegitimately, surveillance and espionage techniques like DPI (Deep Packet Inspection), Phorm, FinFisher, and malwares like DaVinci, and so on. We will see.

BS: Aside from this, are there any other threats to come?

ÖU: Sure, there will be more threats including to Internet publications through an oppressive Press Law; there will be a strengthening of the Internet censorship law (5651); plans to use IDs for accessing the Internet; a PRISM-like surveillance system legitimated by a Patriot-like new anti-terror regulation. This is an escalating game. One side moves forward, other side responds and vice-versa: the duality hypothesis. There will be no clear winner and this battle will carry on.

BS: Despite the censoring mechanisms, social media sites and applications have been the main communication tool for the resistance in Turkey, as well as the only way to spread immediate information and news about on-going events. It is obvious that the Internet has provided a platform for public organisation, beyond the control of the government. On the other hand, the government chose to use the same medium to threaten the public. How do you read these different approaches?

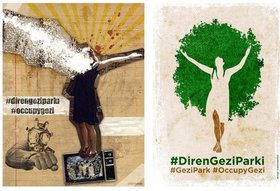

ÖU: The Gezi resistance marked a summit in terms of the innovative use of social media for activist purposes. I always say: to communicate is to be organised. Social media, with its decentralised, distributed, interactive structure and its real-time information stream and exponentially growing content, offers not only highly effective media alternatives, but also very solid organisation tools for gathering, consensus and orienting protests. We have to add another important function of sharing critical information like medical and legal support, or documenting and collecting evidence of police violence. These organisational functions produce a dissuasive effect on authorities and police too.

Technology is neutral. Then the authorities to oppress dissidence too use Internet and social media. As I said, 'this is an escalating game'. The Internet itself has become a major tool of surveillance society. Power mechanisms shift the control society paradigm from targeted surveillance to total surveillance. They spy, monitor and eavesdrop everybody and record everything so as to selectively use s this mass of knowledge later. Of course, this is not legal at all. It is a violation of rights and freedoms like privacy, free expression, anonymity et cetera. The state should be transparent, not the state's citizens. But power mechanisms are going further into the dark with cover operations, drone use, PRISM-like systems. This creates a counter-part too: from protective techniques like anonymisation, encryption, access masking, and VPN, to more subversive tactics like hacking, DDOS attacks, publishing leaks (leak journalism is a legitimate area, even the leaks obtained by radical information capturing methods). Then, if there is a Big Brother, there are a multitude of 'little brothers' using the same dissemination and encryption techniques to resist surveillance.

BS: Beside these surveillance systems, there is also an obvious act of 'fabricating fear' as a tool to control and oppress reacting voices.

ÖU: Authorities use social media to disseminate fear amongst users and intimidate them: this forces them to auto-censor, thus stealing their voice. They use a kind of 'peer-to-peer threatening'. For example, in Turkey we have a number of anonymous Twitter users with police emblems in their profile that target people to intimidate them and use mention tools to report them to the authorities. But they also use aggressive social media marketing tools like bots, spam APIs and others. It's normal, because in Turkey like everywhere else, social media usage is much more common in an urban, educated and dissident population than conservative groups. The authorities try to balance this by employing 'special forces' who police the milieu or automated marketing tools.

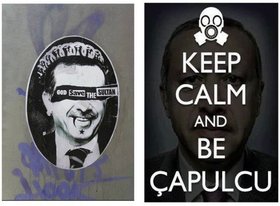

These kind of illegitimate operations may work in normal times and produce inertia amongst people. But in times like the Gezi resistance, they do not because in a situation like Gezi, people have gone far beyond the fear threshold on the streets, physically. Fear in social media is nearly meaningless for them. This was the same experience in Tunisia, Egypt, Spain, Greece, Iran or the USA. Now in Turkey, we have the same situation. Twitter users ironise the cyber threats, mocking them. They share useful information to protect themselves. The hashtag #WeAreHackedByRedHack (#RedHacTarafındanHacklendik) was an example. Then as now, the authorities' oppressive tactics have not worked. Of course, they will develop themselves, for sure. And the dissidence will go a step further, and so on…

BS: In the same context, how do you perceive RedHack?

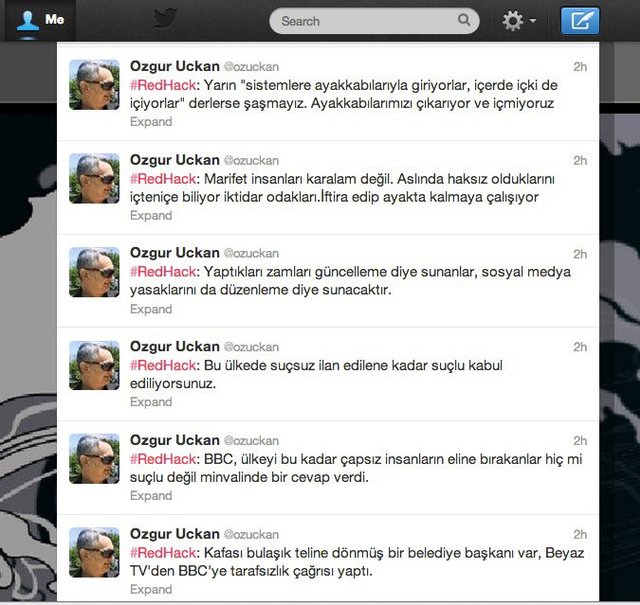

ÖU: Redhack is a well-known hacktivist group active since 1997 in Turkey. They are one of the first hacktivist groups, before Anonymous or LulzSec. For me, RedHack is a typical and powerful little brother in this escalating game. They got popular sympathy with their hacks against electronic state nodes and hubs like YÖK, the Ministry of Interior, the Foreign Ministry, the military, police departments et cetera. They capture a lot of sensible data about state corruption, spying, and informer's networks and publish them. We learn a lot from them. If the state conducts dark and deep operations illegitimately, they will be always their counterpart in the dark. Lurkers.

Publishing a leak for public good is totally legal even if this leak is captured illegally. Attacking Tunisian police state nodes with a DDOS to wipe out activist information may not be 'legal' but conscientiously legitimate. I perceive RedHack and hacktivism to exist in a grey area between law and conscience.

Some links:

'Decentralization/Super-Centralization Clash and Social Movements: Turkey Case (#DirenGezi #ResistGezi)' by Ozgur Uckan – Pas Sage en Seine, 23rd June 2013, Paris. Presentation / Video

ENDitorial: #ResistSocialMedia In Turkey, EDRi-gram newsletter, No. 11.12, 19th June 2013.

Özgür Uçkan, 'Internet 'censorship' increases in Turkey', BBC 'click' interview, 25th November 2011.

Özgür Uçkan, 'Little brothers versus "Big Brother" ' (WikiLeaks: Welcome to the New World Order), 15th - 16th March 2012 / FUTURES AND OPTIONS / SALT Beyoglu - Istanbul. Presentation / Video

Anna Wood, 'Turkey's cyber conflict', SETimes, 16th June 2011.

Anna Wood, 'Social media and politics in Turkey', SETimes, 31st May 2011.

PART 2

'Waking up from a nightmare.'

Vasıf Kortun, responding hashtags, (re-)pos(t)ed by Basak Senova

Vasif Kortun: The Gezi resistance has been a great learning experience for me. Institutional arrogance is something I tried to dismantle to very little success in the recent past. But now the ground is amazingly fertile for change. I have no interest in taking an outsider's view or assume an academic role that is bent on interpretation or distributing wisdom. This is a moment where the knowledge of the situation is not exterior to it at all. The only dispatches I send out to the world are simple reporting. Gezi Resistance is about being alive again, it is about waking up from a nightmare that we'd grown to accept and giving up the withdrawal to our vulnerable privacy, it is about participating in the civic sphere and inventing a new civic condition, it is about reintroducing the fundamentals of urban experience where people of different social classes, ethnicities, beliefs, backgrounds, sexual choices, experiences and professions come together to negotiate.

Vasif Kortun: It does not have to be a consensus; agreement is not the point. It is about producing new forms of institutionality and getting down to and remembering the very basics of being in this world with other beings, plant, animal and human. I am not romanticising here, it has happened and continues to happen in the summer heat and during Ramadan. It is a magnetic context, the closer you get to it the happier you are, the less lonely you are, and the more intelligent everybody becomes, totally stigmergical! There is a lot of work to do in the years ahead, some of it is restorative, others will have to be transformative.

Vasif Kortun: Young people have been amazing, it is up to us the older generations if we can earn their respect. We may have great experiences, we may have had read more and experienced more, but that is not meaningful if we keep on using the same language we did. What matters is adopting to their ways, conditions and methods so that our "archive" can be translated to their archive. They have to connect laterally. I still go to many "classical" contexts when someone gets up and speaks for twenty minutes and expects questions to be asked. Wrong. Broadcast model is dead. We have to get used to it.

Özgür Uçkan (PhD) teaches at Istanbul Bilgi University Communication Faculty, knowledge economy, network economy, innovation economy, creative industries, urban economics, information design & management, communication design related subjects at undergraduate and graduate degree. He teaches also knowledge & innovation management strategies at Yeditepe University MBA programme.

Uçkan's professional activities consist mainly in consultancy and project management services. He is knowledge economy consultant of Turkish Exporters Assembly (TIM), the umbrella organization of Turkish exporter unions. He is member of the Special ICT Commission of Istanbul Chamber of Commerce. He is the founder member of Alternative Informatics Association (AIA). He works as a project-based advisor on different areas such as economy, social and public domain, politics, culture, electronic communication and corporate communication within different national and international organizations, companies, institutions and NGOs. He published several books, articles, papers and reports about economics, politics, human sciences, ICT, culture and art. He is columnist at BThaber, a nationwide weekly information technologies magazine. He published with Cemil Ertem recently a book entitled "Wikileaks: Yeni Dünya Düzenine Hoşgeldiniz" (Wikileaks: Welcome to the New World Order, Etkileşim, April 2011).

Vasif Kortun is a curator, writer and teacher in the field of contemporary visual art, its institutions, and spatial practices. He is the Director of Research and Programs of SALT. Kortun is a member of the Board of Directors of Foundation for Arts Initiatives, and the Advisory Board of Asia Art Archive.

He was the founding director of a number of institutions including the Platform Garanti Contemporary Art Center, İstanbul, Proje4L, İstanbul Museum of Contemporary Art and the Museum of the Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College. Kortun has worked on a number of major biennale projects, including: Taipei Biennale (2008) co-curated with ManRay Hsu, 9th International İstanbul Biennial (2005) co-curated with Charles Esche.