Interviews

Opening Up: World Nomads Tunisia

Marie-Monique Steckel in conversation with Fawz Kabra

In May 2013, the French Institute Alliance Française (FIAF) organized the fifth edition of World Nomads, a festival presenting the diverse Francophone arts and cultures in New York through extensive programs in visual art, music, and performance. Previous iterations included Africa (2008), Haiti (2009), Lebanon (2010), and Morocco (2011). 2013's focus on Tunisia highlighted the country's post-revolutionary cultural landscape, here placed under thoughtful critical evaluation through charged art shows, film programs, and talks by leading Tunisian women on the role of women in post-revolutionary Tunisia's social, political, and artistic scene. Of course, presenting a culture at large can be reductive, but this was not the case with this year's World Nomads Tunisia festival. In this conversation with Marie-Monique Steckel, the president of the FIAF talks about opening up dialogues that would not have been possible before. In the discussion, Steckel stresses that the World Nomads Festival does not have a political agenda. Rather, its aim is to open New York up to Tunisia: a moment to promote and support the work of the various Tunisian artists whose voices emerged after the revolution.

Fawz Kabra: I would like to start with your work. You have referred to yourself as a bridge, and, in the case of the 2013 World Nomads Festival, your work means bridging cultures between France and the United States. Can you describe your position at the French Institute Alliance Française, and as an organizer of the World Nomads Festival?

Marie-Monique Steckel: I see the FIAF as an institution that encompasses all the French cultures, not just France. We work with a broad range of institutions, with diverse cultural interests, and we create and present programming in New York that is not only about French cultures. We collaborate with cultural partners and institutions like the Baryshnikov Arts Center and the Whitney Museum of American Art, to name a few.

We are trying not to be an isolated institution. Instead, we strive to branch out, so that we build new relationships and work with new partners. The same is true with how we approach World Nomads. Five years ago, we decided that it was also important to promote and celebrate cultures from different countries around the world. We wanted to bring these different cultures to New York, and, with this in mind, we decided to expand our programming throughout the city. We did not want to organize events solely at the FIAF headquarters, so we partnered up with different New York institutions to produce the festival. For instance, we worked with The Invisible Dog Art Center in Brooklyn, a project space that collaborates with a variety of artists and allows them freedom of creative expression. We also worked with White Box Gallery in Manhattan, an independent, not-for-profit gallery that maintains an unconventional approach to exhibition-making and programming. It was also very exciting to work with 5Pointz Aerosol Art Center: an outdoor exhibition space that invites graffiti artists from around the world to showcase their works at an old factory building in Queens. For this, we invited 'writer/artists' to participate.

World Nomads stems from a desire to have the French culture present here. So, over the years, we have also organized festivals around other Francophone cultures, such as Haiti, Morocco, Lebanon, West Africa, and – this last May – Tunisia.

FK: Can you explain the idea behind the title 'World Nomads?'

MMS: The reason for the title is that we are not only bringing artists from their particular countries to New York, we are also looking at communities and populations in diaspora. So we are not just looking at artists who live in the country where we are presenting, but also those who have emigrated, lived in exile, or are continuous travellers. For example, in 2010 we worked with Wajdi Mouawad for World Nomads Lebanon, during which Mouawad did a performance with actress and singer Jane Birkin. Mouawad is an important theatre director and writer who sometimes lives in Montreal and sometimes elsewhere. He's very nomadic, in a sense.

FK: So perhaps you can elaborate more on this. How do you position World Nomads Tunisia in our current globalized and transcultural world?

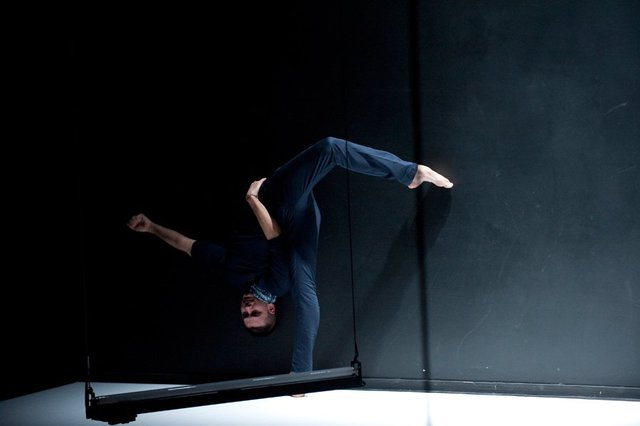

MMS: When I talk about the diaspora, it is to highlight the memory of the homeland. Artists living in their country, in exile, or just living abroad, begin to shape and work with this memory of a homeland. That is true whether you are talking about Lebanon, Tunisia, or Morocco. It is this interplay – an exchange – of the memory of a homeland with the culture of the country in which one is living. For example, this is something that is very evident in the work of Jonah Bokaer. His father was Tunisian, and Jonah was born here, living his entire life in the United States. For his World Nomads Tunisia performance, he created wonderful choreography for his work The Ulysses Syndrome (2013). It is a piece that investigates his dual cultural identity and the issues of migration, displacement, and subjectivity. His choreography imagined Tunisia, the memory of the place, and its sounds. He is a great example of an artist practicing at the junction of memory and exile.

FK: World Nomads Tunisia is the FIAF's fifth edition of World Nomads, and comes two years after the Tunisian revolution. Can you explain the influences that drove the FIAF to select Tunisia, and the significance of the choice?

MMS: There is an enormous bubbling of creativity around the revolution that further propels the desire for freedom and democracy, giving these things an image or a voice. The revolution was also manifested by the works of many young and emerging artists. For example, the young singer and songwriter Emel Mathlouthi, who has really been the voice of the revolution, and who gave a voice to the 'Arab Spring', performed songs from her most recent album 'Kelmti Horra' – meaning 'My Word is Free'.

At World Nomads Tunisia, we presented a selection of truly fabulous young artists who would have never been able to show their works otherwise. We organized these art exhibitions both at our gallery and at White Box. To me, it was a particularly good time to look at the Tunisian art scene because of all these young people who are passionate about their country and its culture. This is providing them with a platform for artistic expression that goes beyond their regional boundaries.

FK: What was that like?

MMS: What the artists came up with and produced was extremely emotional for me. And witnessing their immensely open way of expressing themselves was very inspiring, especially since this type of expression had been suppressed before the revolution.

FK: Any particular highlights?

MMS: Women are the ones who will be the defenders of women's rights. They had previously won a great deal of rights, which are now threatened by the Islamists. Emel [Mathlouthi] was extremely touching. Bokaer's The Ulysses Syndrome was also magnificent, I thought.

'The Role of Women in Tunisian Society' was a talk that connected leading Tunisian women, who discussed the role of women as artistic, cultural, and social leaders following the revolution. We worked with an extremely articulate young woman called Amna Guellali, who is the Director of Human Rights Watch Tunisia. She gave some very interesting insights into what she sees as happening, mainly that Sharia law is not very convincing on women's rights.

FK: How has this changed your perception? Did it change your experience, or what you already knew about the culture, region and its political development?

MMS: Like most New Yorkers, I was not really aware of the unleashing of all this creativity in Tunisia through the revolution. You do not have the opportunity to witness it from here. I went to Tunisia in June 2012 and was astonished by the surge of creativity and artistic expression that was brewing.

As you know, it was forbidden to have graffiti in the streets in Tunisia. So, after the revolution, all the graffiti artists emerged. Tensions and opposing viewpoints remain, however. For example, the painter Mohamed Ben Slama at one point had to run for his life. His view of the future of Tunisia is exemplified by his paintings, which can be rather dark. One of his paintings, Printemps des Arts, was presented at the 2012 spring arts festival at Abdelliya Palace in Tunisia; it was slashed and burned by Islamists, as they had deemed it insulting to God. Ben Slama had to run away to France with just one suitcase.

The idea of this one suitcase is loaded with meaning. It is a symbol that is used by the artist Patricia Triki, who captures images of a young woman with one suitcase in different locations: a room, or on the beach. As the curator of The After Revolution – which showed at White Box and at the FIAF gallery – Leila Souissi said Tunisia is embarking on a boat and nobody is really driving it, and we do not know where we are going to end up.

FK: That is the atmosphere throughout the Middle East right now.

MMS: Nothing is clear. We had a very interesting series of films, curated by Dora Bouchoucha, who is also a prominent producer. She talked about how difficult it had been to do anything in Tunisia before, and it is not even clear that it is easier now. But she is trying to do a lot; make a change.

FK: You were saying that as a New Yorker, you were not very familiar with emerging art in Tunisia, or the cultural landscape.

MMS: World Nomads Tunisia opened a window to what was and is happening.

FK: So how was it received?

MMS: We had a fabulous reception. A critic told me that this was the best programming he had seen. Reviews of the performances really tapped into Tunisian musical tradition, which was an excellent way to spread knowledge on the arts and cultural scene of Tunisia, just two years after the revolution. It provided another vocabulary with which to speak about Tunisia, by means of art rather than only politics. We reached out to a lot of people and had very large numbers visiting the galleries, attending the performances and screenings.

FK: That is true, I read several of The New York Times articles, and was very impressed by how the writers of these reviews took the time not only to describe, but to also interpret – and define – Tunisian terms, traditions and histories. I am also curious to know how you think of this in the short term or long term. Do you feel something more will emerge from the relationships you have built with Tunisia, Tunisian artists, as well as the various institutions during the festival?

MMS: Well, I certainly hope that we can continue our relationship with our supporters. We are certainly interested in doing more on the Middle Eastern region. We have made connections with some Tunisians in New York who I would have never known otherwise. We had a committee of the 'friends' of World Nomads: about 70 people. The Tunisian embassy helped as much as they could. They expressed that they would have very much liked to do what we are doing at the FIAF, but felt that they could have had a lot of trouble programming it. Their situation is complex. Ministers are not sure that they will be ministers tomorrow.

FK: Do you think there is an urgency in starting a dialogue between the Maghreb/Middle Eastern region and the so-called western world? As I see it, your work in cultural diplomacy is extremely instrumental here, as you have stepped in to 'open a window', as you say, to the artistic and cultural scene of Tunisia. When you say that culture ministers are not sure if they will be ministers tomorrow, I agree that this seems to be the situation in many countries in transition, such as those in the Middle East, and even Eastern Europe. What are the ways that we can reimagine working on a large scale, yet outside of the classic institutional framework? How can we work 'officially' and with broad cultural impact, even if 'the ministry' is unable to lend a hand?

MMS: Working with Tunisia now is difficult in terms of the institutions. There is nobody that you can talk to, so for us there was very little sponsorship, or even support, from the 'official' Tunisians in Tunisia. This compelled me to seek support through different channels. I have made wonderful friends and I want to continue working with them on a personal level.

I think that tolerance comes from knowledge, and that opening eyes and ears to a very rich culture, like Tunisia or Morocco, is extremely important. I am very happy that the FIAF can help in opening up new worlds and exposing New Yorkers to the rich and dynamic cultures of these countries.

FK: You say that tolerance comes from knowledge and that World Nomads Tunisia aimed to open eyes and ears to the very rich culture of Tunisia. It is so important to support and promote the work of emerging artists, or artists who are conscientious of the future of their cultural landscape, such as Ben Slama. I am also considering the new friendships which have blossomed as a result of the inability to access support from the official sources in Tunisia, as was the case with the embassy here in New York. How do you see this growing further? And how is this festival an instigator of new dialogues?

MMS: We are not the only ones trying to have a dialogue with Middle Eastern countries. Neither can we say that we are the sole bearers of this project. But I will give you an example: 'eL Seed' is a very talented graffiti artist who was invited to the festival and did amazing work in New York. Now that a door has been opened for him to exhibit his work here, he is going to come back to work on more projects. If other branches of the Alliance Française can help him – and others like him – I would be delighted to open the door to that. The same is true of other artists; if they want a future exhibition here, we would be delighted to market or sponsor some of it. These threads that we have are personal, but they are also connections that we have to nurture. They are not only friendships; there is a certain reciprocity that is taking shape.

FK: Was there a Tunisian presence in New York before the festival?

MMS: I couldn't even find a Tunisian restaurant! Tunisia is a small country in a way – only 12 million people. But to think of all the artists that come from there is amazing. The intellect and creativity coming from this vibrant country is very inspiring. I hope that our festival will spread new knowledge to a number of people here in New York.

FK: When one is dealing with communicating the richness of cultures – perhaps those that need regional representation – and when one is involved in projects that build bridges of understanding and appreciation, how can one ultimately drive projects that are positive and eye-opening, while remaining critical, so as to not reduce or simplify the region's complex realities?

MMS: I think art is essential to the aura of a country. It is the most important thing you can circulate and communicate. We feel that way about France: our best products are ideas and art. The same is true for Tunisian art, and not having it in New York is a missed opportunity, and an unfortunate lack of an important presence. We are very happy to have been able to bring a lot of people from Tunisia over to New York. Immersing the arts, languages and music of one region with another is an impressive sight. What people take from it, what kind of results this exchange creates, is so important. It creates an opening up of views and a challenge to preconceptions.

FK: So you believe that the arts are instrumental in opening up a serious conversation, and in cultivating forward-thinking communities and societies?

MMS: We did not want it to be a political conversation. We took great pains not to enter into the politics of Tunisia. We instead showed the artistic landscape, which of course is loaded with the complexities of the region's history, and makes visible the results of the country's politics. Using this set of terms – the arts – we opened a window to a place where the landscape has drastically changed, both culturally and politically, in the last two years. We wanted to show the wealth of this culture; its creative and intellectual intricacies.

Marie-Monique Steckel has an extensive professional biography. As president of the FIAF since 2004, she is credited with expanding the organization in new directions. She spearheaded the French Industrial Development Agency, now called Invest in France, an agency in the United States that promotes American investments in France. Steckel founded the France Telecom in North America, and in 1979 was appointed president of the company. She also worked with Jacques Chirac as the National Director of Communications of his political party, Rassemblement Pour La Republique, in 1977.