Projects

The One That Got Away

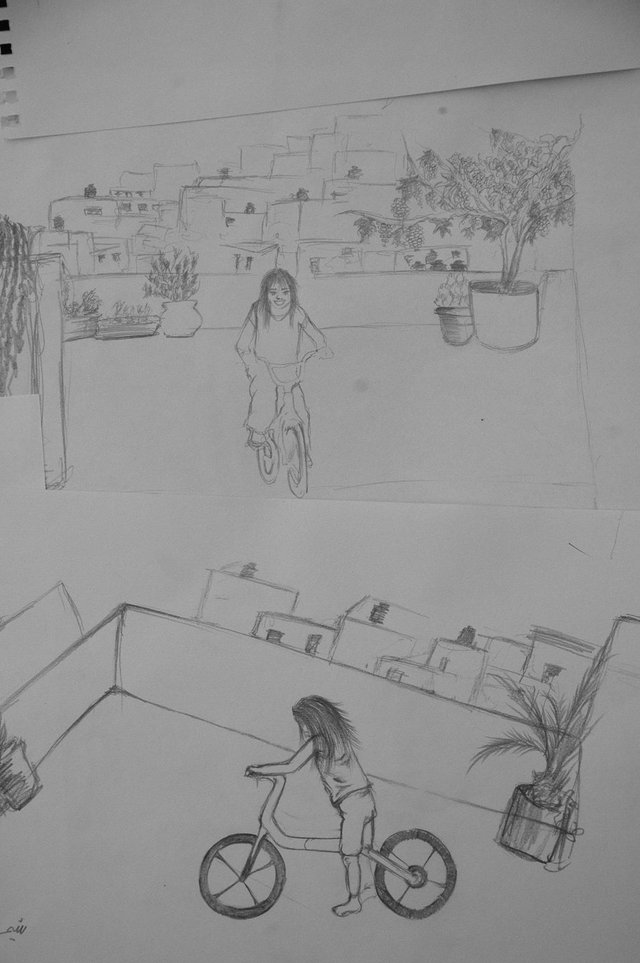

On the Rooftop

'The one that got away' is a collection of stories about moments that I have failed for various reasons to photographically document. Those moments where time, chance and the camera were not rightly aligned. They were the best photographs that I took, if only I took them!

While these lost images continue to haunt me, 'The one that got away' is an attempt to come to terms with their loss and possible potential, a chance to resurrect them from my memory and release them into a possible future.

On the Rooftop

(1)

It is 2005, and I am commissioned by Across Borders, a project by the Centre for Continuing Education, to photograph Hussam Khader, a member of the Palestinian Legislative Council who is an active voice for the Palestinian Right of Return. [1]

Khader has been recently detained as a political prisoner in the Hadarim Detention Centrein the Negev. His fate is unclear, as Israeli authorities have put him in detention for months without any set dates for trial. With no possibility to visit Khader in prison to speak and photograph him, I am set with the challenge of having to create a portrait of a person I do not know and cannot meet.

I find myself heading north to Balata Refugee Camp in Nablus, where Khader once lived. My phone rings to both confirm and postpone several scheduled appointments with Khader's family and friends. One of Khader's friends, who, for the purpose of this story we will refer to as 'X', is particularly insistent. He is the one appointment I am trying to avoid and am unsuccessfully unable to cancel.

'X' has been kind enough to be an introductory link, setting up several appointments with Khader's collogues, friends and family. Most importantly, he is facilitating my visit to Khader's house to meet with his eight-year-old daughter Amira. But word reaches me that X's services are part of his notorious womanising ways - ones he uses often with female journalists or activists that express an interest in Hussam Khader's case.

At the Israeli checkpoint at Huwara junction, separating Nablus from the south of the West Bank, my post-traumatic stress swings into full force. I am panicking and all possibilities seem equally stressful. Will I pass? And if I pass will I get there in time? But what if I pass and I am stuck there? Would I be stuck with 'X'?

With time on my hands, my imagination starts running wild. My instincts are cautioning me, while my mind is trying to rationalise things. How inappropriate can 'X' possibly be?

After three hours on the checkpoint, I am finally at Balata Camp, a strong resistance point for the Israeli occupation during the bloody events of the Second Intifada. I surrender myself to the fact that my task is to communicate the story as Hussam Khader tells it, or rather, as it is told through Hussam Khader's friends and community. My first stop is Khader's political office where I will be meeting Khader's colleagues. This is where Hussam Kahder's political story starts to unravel.

This is not Khader's first experience as a political prisoner. As a member of the Fateh Organisation, he was arrested several times and in 1988 he was deported by Israeli Authorities to southern Lebanon, returning to Palestine in 1994 after the peace process was initiated.

While in south Lebanon, Khader connected with other Palestinian refugees and consequently felt that the concessions of the Oslo peace process were jeopardizing the Right of Return. He also questioned Yasser Arafat's political and managerial leadership and spoke openly and publically about the corruption surrounding the Palestinian Authority.

As a result, many of Khader's friends and community feel that his detention along with other young prominent young leaders such as Marwan Barghouti, is convenient to both the Israeli authorities that is crushing all kinds of Palestinian resistance, yet also equally convenient for senior Palestinian political leaders who are now spared any kind of real internal political questioning.

As his friends and colleagues are narrating a political portrait of Khader to me, my eyes look around the office for clues that can translate the narrative visually, despite Khader's absence. I pick up my camera and begin to compose the visual elements of the small room, made up of a chair crammed to the wall behind a wide desk. It is a modest scene, a far cry from the extravagance and prestige one would expect from a member of the Legislative Council. Nor does it convey the usual national heroic cliché's embodied through the customary displays of political medallions and trophies.

I snap away, though I know the scene is not photogenic. I am unable to compose the elements together in a way that transcends the immediate description of the office so as to capture more of Khader's brave, idealistic and stubborn spirit. I cannot imagine Khader, who is also a playwright, drinking coffee and drafting a play on this desk. There is something uninspiring about the scene. The neon office lighting flattens all the fascinating layers of Khader's story.

I made a conscious decision to steer away from a typical portrait of a political prisoner, whereby a family member or a friend holds up a picture of Khader. So I must keep searching for a more profound frame.

'X' shows up at the office for the much-dreaded meeting. I set up my recorder and I ask him a few basic questions. He responds to my questions with questions - about my personal life.

'Are you married?'

'Do you live on your own?'

'I am sure you must have a boyfriend. It is ok, you can tell me these things, I am open minded like you.'

He realises that his line of questioning will not distract me from my ownline of questioning, so he goes on a monologue about his love life. Five minutes later, I alert him that I am running out of batteries and therefore I must leave immediately. He insists on sending a young boy from the office to get some batteries for me. He also orders a lollipop and offers to get me one as well. I politely decline.

I am recording this very awkward conversation while he is now sucking on his big lollipop. I am beyond embarrassed. Does he not care that I am getting all this sexual harassment recorded on tape? When did it become appropriate for fully-fledged Palestinian men to suck on lollipops? This reminds me of the time my old boss called me into his office to see his newly purchased underwear!

My post-traumatic stress is in full swing again. I start fidgeting with my camera. I unload the film even though I still have a few shots left. I look through my bag for a new film roll. I examine the recorder. I only have 15 minutes of tape left. I jump out of my chair and firmly declare I am out of tape and must leave immediately to meet Amira.

At Khader's house I am finally feeling a sense of calm. His mother takes me around the house and introduces me to eight-year-old Amira. Her pale face and coloured eyes are haunting. She goes through the motions but barely says a word. In a last effort to break the ice, I ask her to take me to her favorite place.

Amira takes me to the rooftop, which Khader has transformed into a lovely garden shaded with vine leaves. It overlooks the condensed monotone buildings of Balata Refugee Camp. With a smile slowly creeping onto her face, Amira picks up her bike, a gift from her father, and starts roaming around the rooftop. This rooftop is her main outlet since, as a girl, she is unable to ride her bike on the street.

Alas! I finally find the image I am looking for. The view of the camp from the rooftop is amazing. The garden is Khader's defiant spirit: his ability to transform his own condition. I imagine Khader sitting here to write his plays. InAmira's smile I see Khader's warmth as a father.

Excited, I take out my camera and compose the scene so that Amira and her bike are in the foreground shaded underneath the vine leaves, while the rest of Balata Refugee Camp recedes into the background. I ask her to hold on to the bike and look straight into the camera. Then I start following her movement as she cycles around the roof. She almost forgets I am here.

On the way back to Ramallah, I enthusiastically call my boss from the Centre for Continuing Education to inform him of the great results of my trip. I can't contain my excitement - I really want to see the images, and hold them in my hands. So I ask the driver to make a quick detour to the photo developer. I manually rewind the film wheel, pop open the film back and to my shock, there is no film in the camera.

A special thanks to Toleen Touq for her support.

[1] The Palestinian Right of Return is the right of Palestinian refugees and their descendants to return to their homes and property from which they were uprooted in 1948 and 1967.