Projects

My Dick in My Dick, Kiss Me Again, After Eight, All Mother Tongues Are Difficult and their sisters.

Awkwardly, inspired by Louis Wolfson and his Le Schizo et les langues, I spent a week with schizophrenic people in an asylum near Antwerp where I thought having contact with them daily would allow me develop my knowledge of the Dutch/Flemish language. I loosely organized a workshop with them, and invited them to write love letters, which we would read to each other in small groups or individually.

Louis Wolfson wrote a whole book in his self-taught French titled Le Schizo et les langues while he lived and grew up in New York. A few years later he wrote another book about his mother's vaginal cancer and his love of gambling. His books are mostly autobiographical and I feel very close to that, considering most of what I do stems from autobiography, from my daily life, even if this often remains concealed.

This was one of the first experiments I tried as soon as I embarked on my ongoing research into language - spending a week in an asylum in order to learn Dutch/Flemish, while in fact I had to learn Dutch in order to pass my integration exam for filing an application to ask for the Dutch passport in the Netherlands, not in Belgium.

I had twisted this governmental obligation, and favoured trying to learn Dutch from Antwerp instead of Amsterdam, just like a number of those who tried to learn Arabic went to a school in Damascus or Cairo, even if they planned on working later in Beirut. Learning Arabic from Beirut, where everyone is so happy and blasé about forgetting their Arabic is impossible. Something similar happens in Amsterdam to those who try to learn Dutch, if their English is already developed. The Dutch love speaking other languages with foreigners - I even have a Dutch friend who occasionally speaks Yemeni to me rather than Dutch, because he had lived a couple of years there for some work and for a love story.

In the asylum I encountered an artist who visited and stayed in the asylum for a few days a week, and who wrote a beautiful poetry piece in Flemish. I also encountered at least five people from Moroccan origins, and a woman who is Kurdish and who had grown up in Turkey.

A few of the Moroccans (mostly the people who were some ten years older than myself) favoured writing their love letters in Arabic. Those who grew up in Antwerp don't speak Arabic (more than a few words), and do not write it at all.

My collection of love letters from that time is a mix of Flemish, Arabic, English (a couple of young guys from Antwerp favoured writing in English as they felt more free to express themselves in the hip-hop language, them being big American hip-hop fans), and the Kurdish woman wrote quite good Flemish, but sometimes liked to use Turkish in her love letters, to include her favourite songs and relevant expressions.

After I spent a week there in 2012, I put all those letters to one side, and considered them as part of my research, but did not know what to do with them at all. It was all rather overwhelming, as you can imagine. Some of them consisted of drawings, where language was not useful and residents in the asylum preferred to make drawings to tackle their love issue rather than writing about it.

After having continued with several projects and works related to language, and only two years later, I was able to decide that yes, I would like to include some of those love letters in the third issue of NOA (Not Only Arabic) magazine which I am now finalizing. But I won't use the letters, I'd rather invite certain people react on them and include these 'reactions' in the magazine.

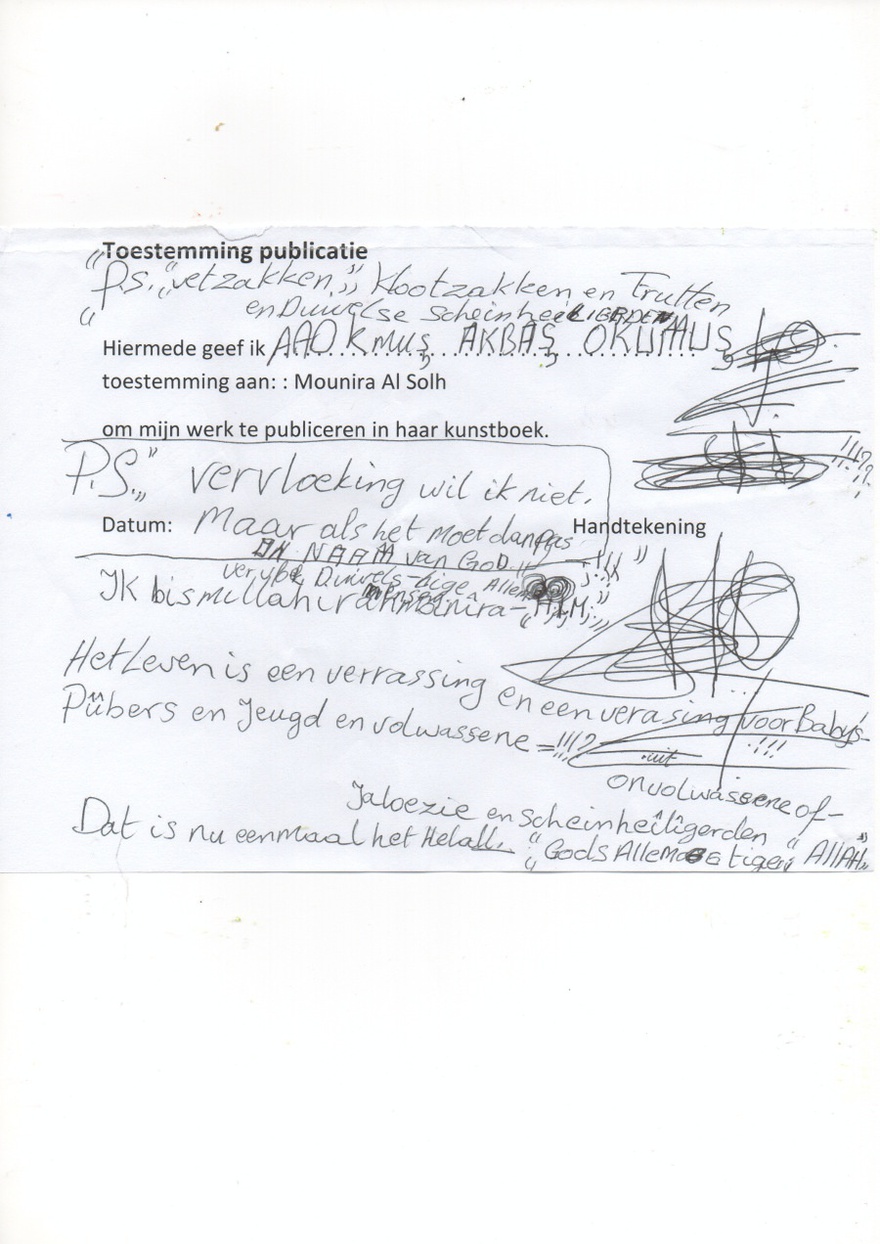

What matters now to me is the process, and most importantly, the manner in which each of the people residing in that asylum near Antwerp interpreted 'love', 'the love letter', and even the 'toestemming', which means 'the permit' that they signed, allowing me to use their love letters in my work. It was often a 'failed' love story, that had ended up in hate, and if it was not that, it greatly exceeded my expectations. While I thought I had invited them to think of the notion of love in general, as an existentialist matter, most of the residents in the asylum proved to me that love only matters to be written about, when it is a failed and a personal love story. No one was interested to write about a 'successful love story', or about 'love' as an existential matter, except for the one who studied art.

I will let you imagine those letters now, and here below I have compiled an attempt to group intermittently some of my findings, works, relevant texts, drawings and paintings that contributed and still contribute to my ongoing language research.

I grouped them under an alphabetical order, replacing each alphabetical letter by a word that starts with this letter, or by a sequence of letters (such as KLMN).

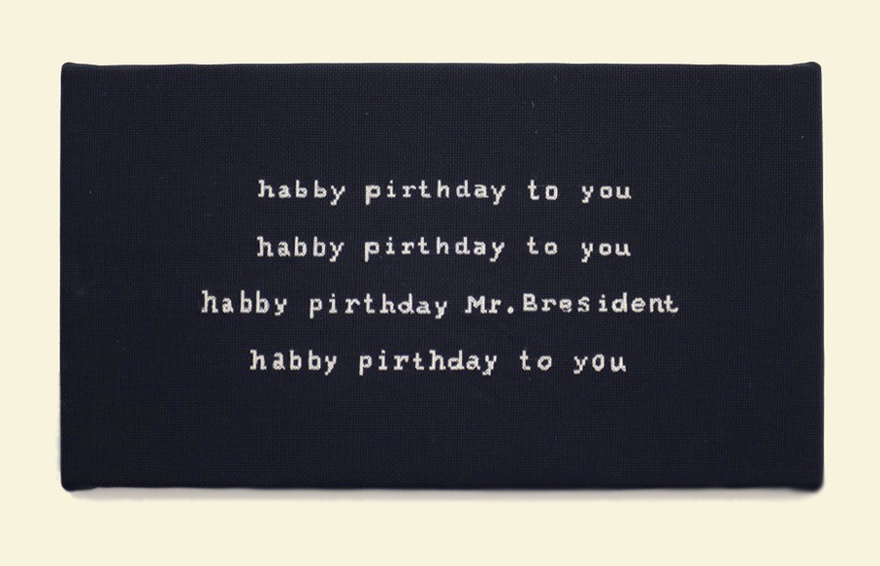

Some of those are part of a work titled After Eight (2014) and another one titled All Mother tongues Are Difficult (2014), which consist of a number of embroideries and hand-stitched media.

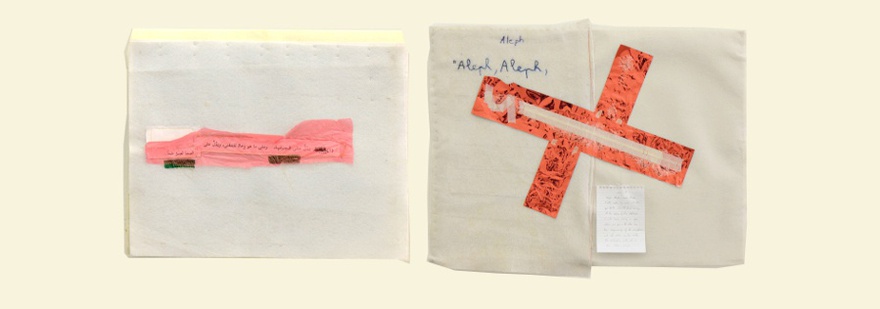

1. Aleph

It is as if the sound of aleph has been forgotten by the people who once produced it: of the many modern pronunciations of Hebrew, not one assigns any sound to the letter, and in all of them aleph is treated as the silent support for the vowels it bears, deprived of even the non-sound, the interruption in articulation, it is thought to have once expressed.

2. Babel

He sees reminders of impending doom in fashion trends like faded denim jeans, and reads the advent of the apocalypse in the infamous inability of Beirutis to stick to one language, generally preferring to speak a mix of French, English and Arabic, and none of them well. This is Babel again: God punishing the nation, confusing its tongues and scattering its people across the world.

How to tell stories, then, after the breakdown of language? In a conversation between Hannah Arendt and Günter Gaus: 'What Remains? The Language Remains,' Arendt stresses that what remained from pre-war Germany for her was only language.

3. Chorus (false Chorus)

Excerpt, ongoing work titled Enta Omri (2014-ongoing) Audio work in progress. (1 minute, 37 seconds).

4. Dutch/English Dictionary that I recently got as a present.

It's in fact English/Dutch, but I try to use it as if it were Dutch/English: reading the explanations first, and the translations to Dutch, then finding out what word that was in English.

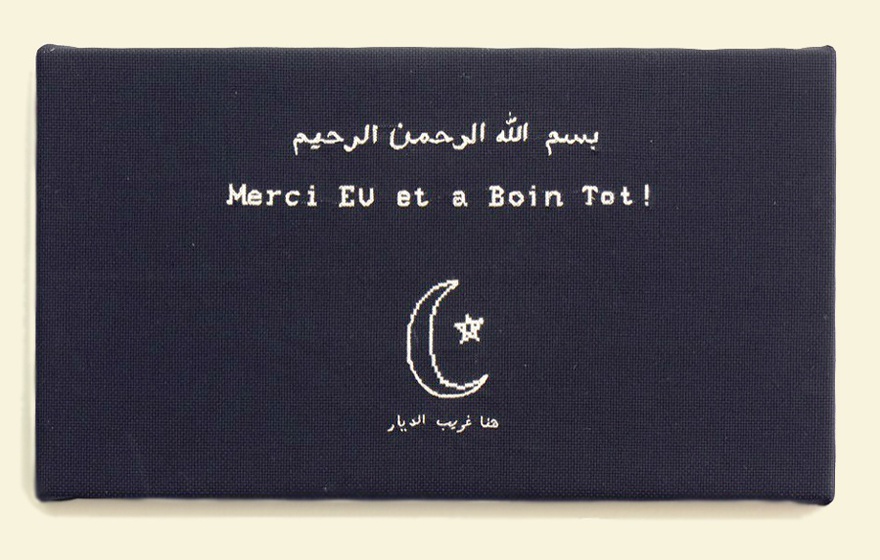

5. Encyclopaedia and EU

Every respectable family should inherit an encyclopaedia: a dark purple leather Britannica with its brown pages, a simplified red leather Hachette? A child would get a bit older, wait for her parents to sleep, and start cutting out all the images from these inherited and smelly encyclopaedias. She cuts out Um Kalthoum from Hachette. Words don't count. Encyclopaedias that once pretended to contain all the true Truth. The grown up child was thinking, if this were true, why do we need a new edition of the Encyclopaedia once in a while? Does Truth change once in a while?

And a year later, the digital era came, Encyclopaedia sellers panicked at first, then they started advertising tens of valuable and complete Encyclopaedias on a CD by calling people's homes and convincing them to buy it for their children and the future of their children.

There was one on art, another on classical music (by the way, what does classical music mean?), and another one on general knowledge. This is where the coloured picture of Umm Kulthum with a typical white scarf between her hands is printed, like other pictures of birds for instance, very colourful as opposed to the other black and white neighbouring images, they live on the same page, or on another page in the Encyclopaedia.

Most beautiful are the names of Encyclopaedias in Arabic at a certain time: if we translate them literally and from memory they'd be like: The Sea of the Seas, The Tongue of the Arabs, The Ocean of the Ocean and so on. They rhyme.

6- F becoming kh and kh simplified into a hh/ح --

In English, for example, consider the common exclamation of disgust 'ukh', which involves a constrictive consonant kh (reminiscent of the sound transcribed by the Castilian letter jota or the Arabic letter خ),and which appears in some languages in distinctive opposition to a velar k (such as in Dutch), or a more fully guttural h, but which has no proper place in the sound system of English.

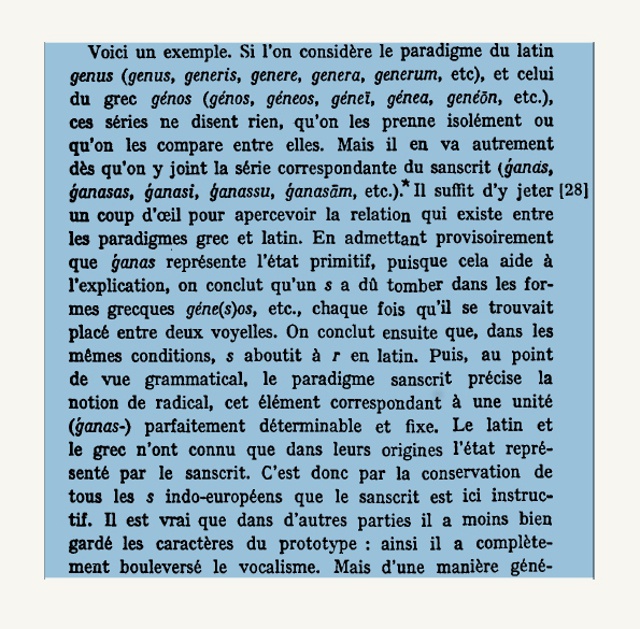

7. Genius

8. Hage

Jacques Aswad asks himself why did Kamal Youssef El Hage choose to say in Arabic (when literary translated): 'The Mother Language', and not 'The Mother Tongue'?

What is the difference between a language and a tongue in this context? Kamal Youssef Al Hage claims to be the first who has created the term "Mother Language" in Arabic. Language allows us stick to sand, and so we can float above it, above its animosity.

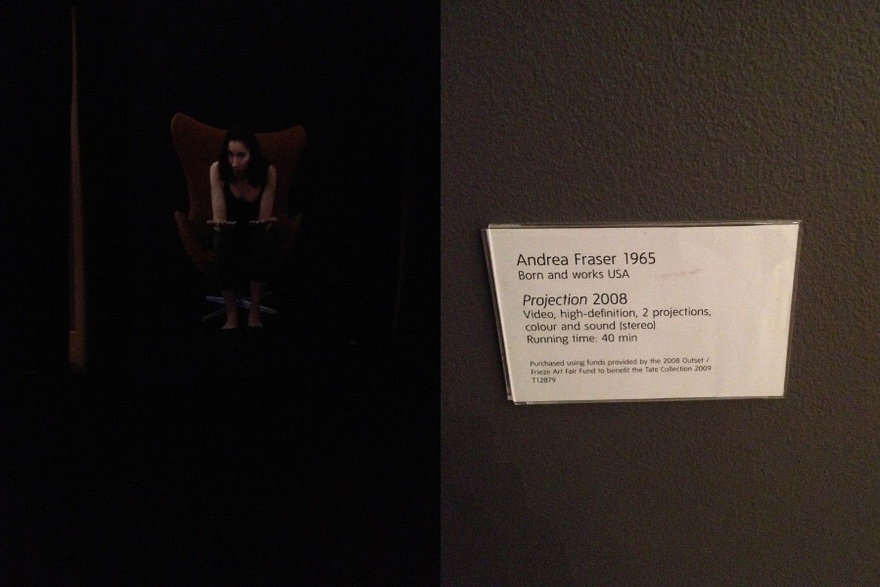

9. Institutional Critic

A beautiful crying woman, now in a video still made by my iPhone last week, from your big museum

10. Juliet

Particularly in Shakespeare's theatrical staging of the myth, Romeo and Juliet themselves seem to understand that their story - what is happening to them alone - is also this 'other' tragedy of the name into which they too have been 'born' - 'from forth the fatal loins of these two foes.' Juliet, especially, analyzes their predicament in precisely this way during the balcony scene - moving from their names to names in general, from 'Montague' to 'Rose,' from 'Romeo' to 'love'. Indeed, it is this collision of their lives - their desire, their relationship, their interactions - with their names that lie at the source of the tragedy, the heart of its mythos.

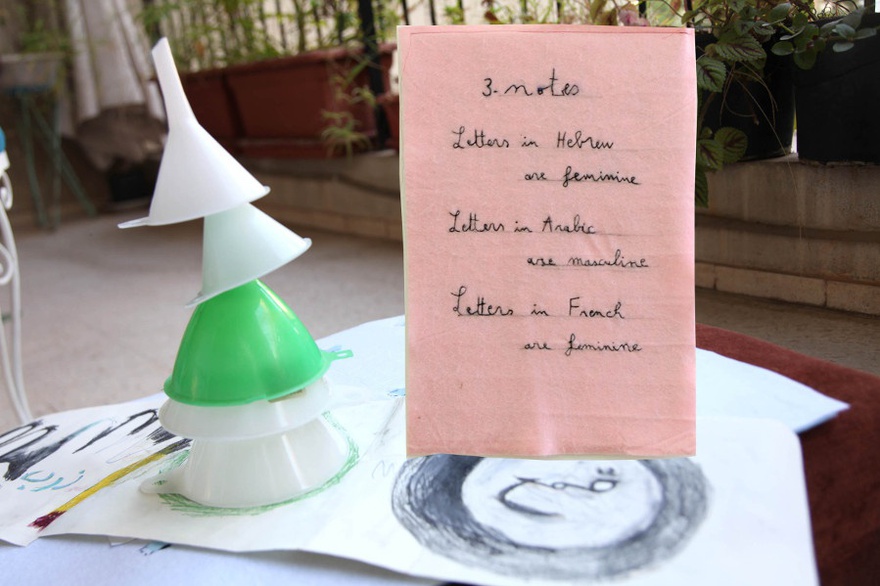

11- KLMN (Kalamon) in Arabic كلمن

Ahmad Beydoun wants to strip the king Kalamon, bring him back to one letter only, in other words, kill him.

The sequence of the letters K,L,M,N, in the Arabic alphabet, as well as in the Greek one, the Latin, and the Assyrian, the Phoenician one and so on, remains with those unique four letters as such: K,L,M,N.

K comes first, followed by the L, followed by the M, and finally the N. It's an ideal sequence it seems, otherwise, why did all those alphabets keep it this way?

Kalamon is the king of the kings in the Arabic language, the letters of his name are those retaining the word (Al Kalam), therefore he is the strongest.

The other kings are Abjad, Hawwaz, Hatti, Saafath and Qarshat.

Kalamon was the king of the kings of Madyan.

Abjad according to some stories was the king of Mekka and the Hijaz.

Hawwaz and Hatti were two kings of Taef and Nejad.

Saafat and Qarshat were kings of Madyan.

Each king wanted to have their own new letters in their name. None of the same letters can be repeated, meaning each king reserves a few letters for his name only. The other kings ought to choose other letters. A simplified and romantic story of how the Arabic alphabet was created, but what matters in this story is the fact that the letters are preserved in the names of the kings.

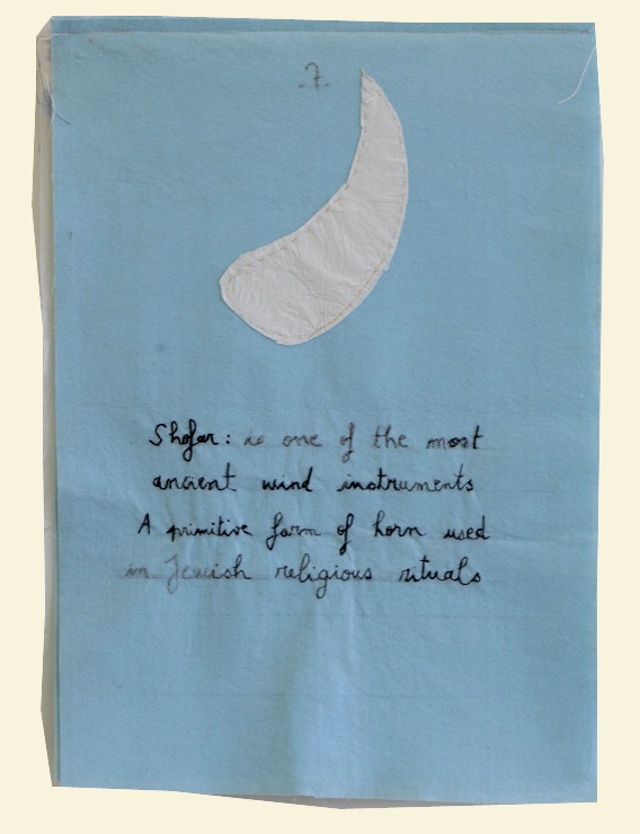

12. Shofar, or the letter O in the instrument Shofar

13. Present/Past

'So, what if, instead of the past being past and the present being present, the past was in the present? What if every second that passes contained the totality of the history of humanity and all its possible futures? What if every fragment, all what we see around us, contained the totality of the universe?' writes Tony Chakar.

And then he quotes Ibn Arabi: 'You think of yourself as nothing but a small speckle, and yet the larger universe was folded into you'.

Ah! As I remember now, one of my notes claimed that in Mandarin, there is no past tense.

14. Q, R and Sign

This inflation of the sign 'language' is the inflation of the sign itself, absolute inflation, inflation itself. Yet, by one of its aspects, or shadows, it is itself still a sign: this crisis is also a symptom. It indicates, as if in spite of itself, that a historico-metaphysical epoch must finally determine as language the totality of its problematic horizon. It must do so not only because all that desire had wished to wrest from the play of language finds itself recaptured within that play but also because, for the same reason, language itself is menaced in its very life, helpless, adrift, in the threat of limitlessness, brought back to its own finitude at the very moment when its limits seem to disappear, when it ceases to be self-assured, contained, and guaranteed by the infinite signified which seemed to exceed

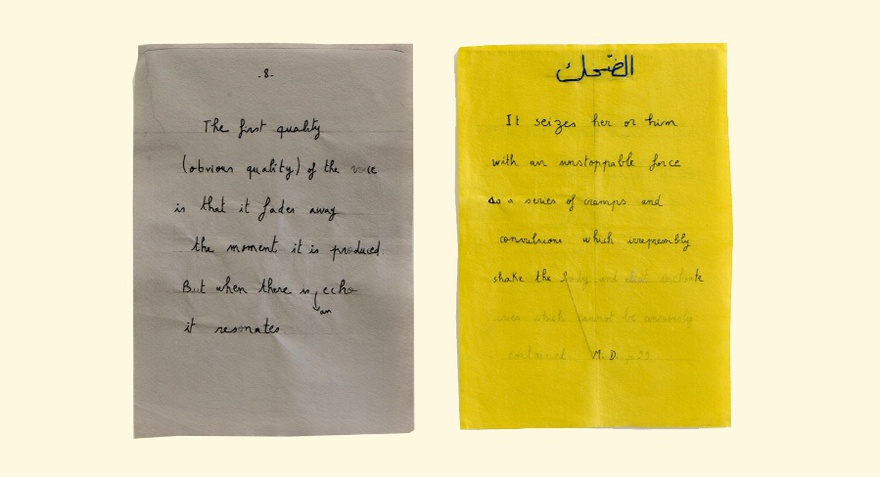

15. Toestemming/ تصريح

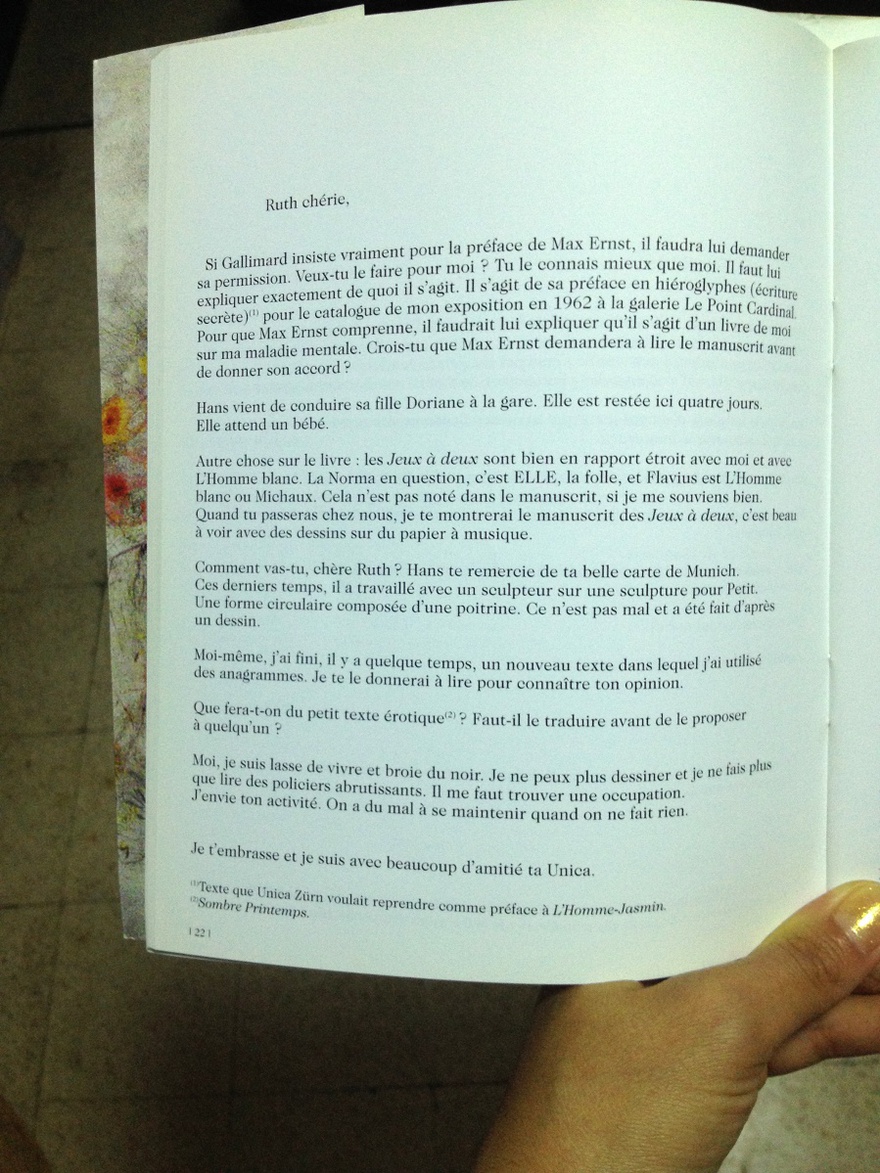

16. Unica

Ruth chérie, Si Gallimard insiste vraiment pour la preface de Max Ernst, il faudra lui demander sa permission.

17. Vord or Word

In the Hebrew tradition, the sacred Word is first of all a sonorous event, a fact that is confirmed in the very name of the Bible: miqra, or 'reading proclamation' (from the verb qara, 'to call, to proclaim, to declare' - present also in the term Qur'an.) In the Christian tradition, on the other hand, the Word is crystallized in writing, as it becomes graphèlgraphai, namely Writing/Writings, or Biblia, the plural of the Greek biblion [book].

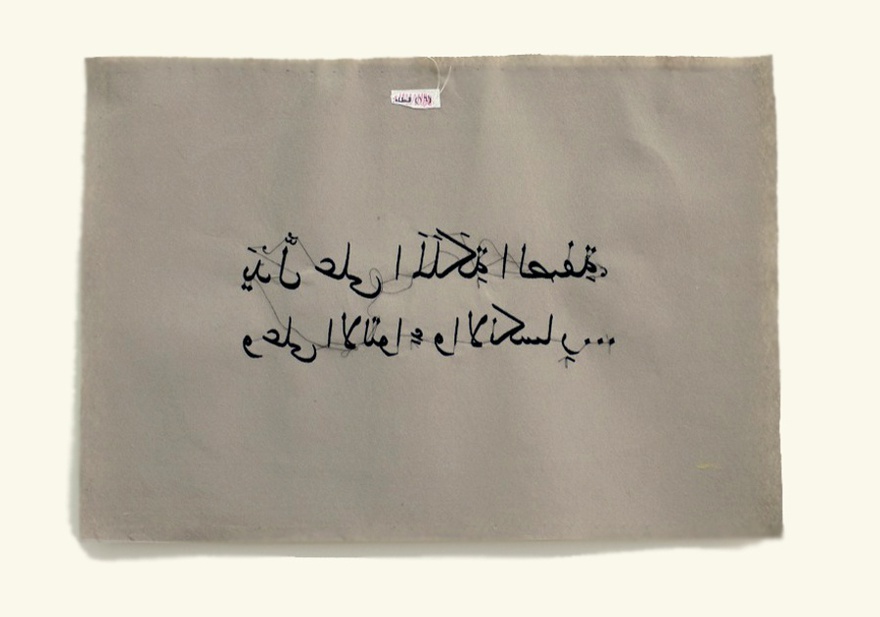

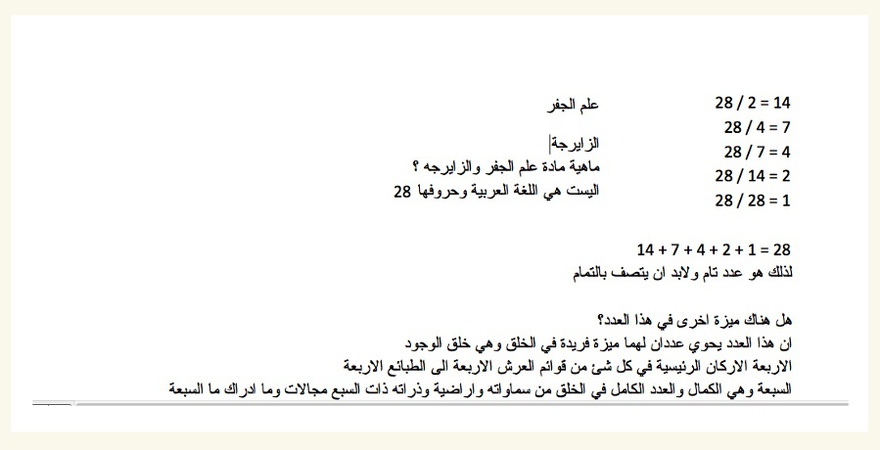

18. X, Y, Z Zayraja

It's a 'science' that claims to be about the numbers of letters in the Arabic alphabet: 28 letters, a number of them are from the moon, others

from the sun, but this evident element is not what matters for Zayraja.

A loose bibliography of the texts and the images listed above:

1. Text: Daniel Heller-Roazen, Echolalias: On the Forgetting of Language (Cambridge, MA: Zone Books, 2005).

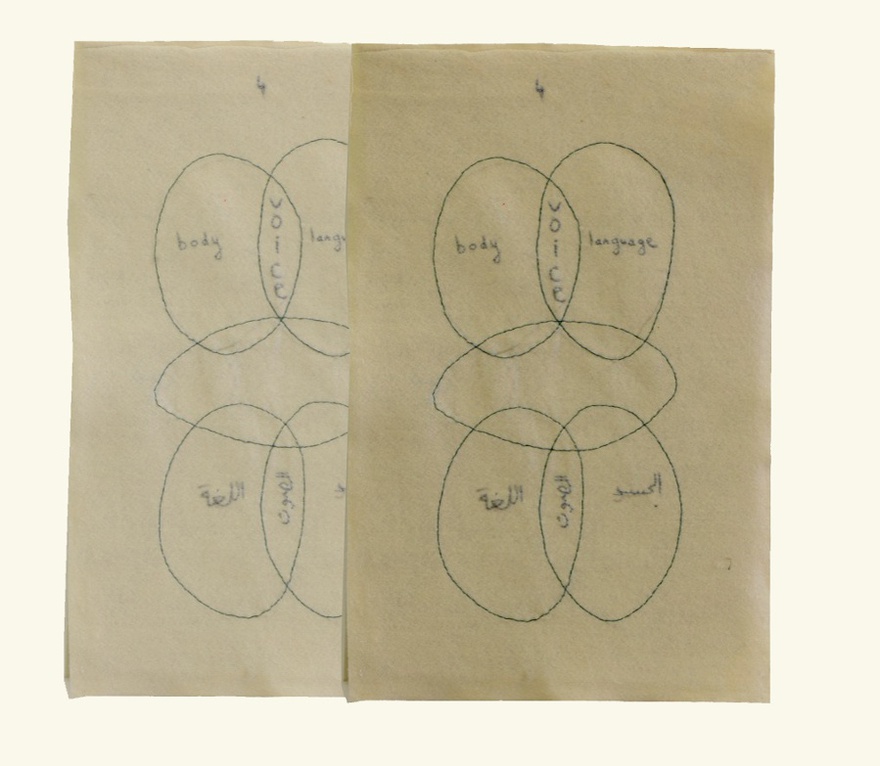

Images: From After Eight, hand and machine-stitched works, with nylon, tape, paper, pen and threads on felt, 2014.

2. Text: Haig Aivazian, 'Tony Chakar: On Black Holes', Afterall: A Journal of Art, Context and Enquiry 35 (2014).

Image: From After Eight, hand and machine-stitched works, with plastic, paper, pen and threads on felt, 2014.

3. Audio fragment with video accomplished for the Ibraaz version of the work from: Enta Omri, ongoing audio work, 2014.

4. Image: Digital Photograph, remodelled for Ibraaz, 2014.

5. Image: From All Mother Tongues Are Difficult, Hand-stitched Embroideries, white threads on black embroidery textile, 2014.

6. Text: Echolalias (Heller-Roazen op cit.)

Images: From After Eight, hand and machine-stitched works, wood, nylon, paper, bubble red wrapper on felt, 2014.

7. Text/Image: Ferdinand De Saussure, Cours de Linguistique Generale, (Lausanne: Payot, 1995).

8. Text: inspired by 'Arabic, My Mother', a lecture Jacques Aswad presented at Sfeir-Semler Gallery in Beirut about Kamal Youssef El Hage, on 11 June 2014, during my show All Mother Tongues Are Difficult.

Image: After Eight (2014) and other works floating and 'photoshopped' on my balcony.

9. Image: Mounira Al Solh, at Tate Modern in London, 2014.

10. Text: From the personal invite letter NOA (Not Only Arabic Magazine) III, and from Adriana Cavarero, For More Than One Voice, Towards a Philosophy of Vocal Expression, trans.Paul A. Kottman (Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 2005).

Image: from "After Eight", two hand-stitched works on felt.

11. Text: Inspired by Ahmad Beydoun, Kalamon (Beirut: Dar Al Jadeed, 1987).

Image: From After Eight/self appointed kings (2014), watercolor, ink, pen and threads on paper.

12. Image: After Eight (2014), pencil and hand-stitched thread on tissues and felt.

13. Text: From Tony Chakar, 'To Speak Shadow,' Afterall: A Journal of Art, Context and Enquiry 35 (2014), and from my notebook on language findings.

Image: From All Mother Tongues Are Difficult (2014), hand-stitched white thread on black embroidery textile.

14. Text: Jacques Derrida, 'The End of the Book and the Beginning of Writing,' in Of Grammatology, trans. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak (Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, 1998).

Image: From After Eight (2014), threads and pencils on felt.

15. Image: A photo of the permission addressed to me by Akbas who resided in Antwerp's asylum, and that allows me use of the love letter she has written during the workshop I gave there. The point of the workshop was for me to learn Dutch/Flemish - amongst other things I learned about myself.

16. Text: Unica Zürn, Lettres a Ruth Henry, 1967-1970, Le Son Lointain.

Image: An iPhone picture of page 22 of the same book.

17. Text: Adriana Cavarero (Idem)

Image: From After Eight (2014), reversed laser machine sewing, paper and red pen on felt.

18. Image: a still from notes on Zayraja and the Arabic alphabet.

With thanks to:

Stefanie Baumann, Philippe Farah, Fadi Tofeili, Angela Serino, Robert Haddad, Alan Quireyns, Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Mladen Dolar, Jacques Aswad, Ahmad Beydoun, Ghalya Saadawi, Dima Hamadeh, Mirene Arsanios, Arnisa Zeqo, Sara Giannini, AIR Antwerpen and Sfeir-Semler Gallery Beirut and Hamburg.