Publications

FIELD MEETING Take 4: Thinking Practice

Closing Remarks

The following text represents an expanded version of the closing remarks delivered by Ibraaz Senior Editor Stephanie Bailey as part of Field Meeting 4: Thinking Practice.

First of all, I wanted to say thank you to Leeza Ahmady for inviting me to participate in Field Meeting 4: Thinking Practice, and to everyone involved in making this happen; especially the presenters.

It is an honour to be offering final remarks on what has been a remarkable gathering. Of course, this honour is also a challenge given the scope of contributions we have seen over these past two days, and the task at hand, which is to offer a summary of sorts. Yet this challenge also fits with the subject of this meeting: practice, and what that means, especially when taking into account the multiplicity of practices that have been presented. These range from from Jennifer Wen Ma's interpretation of Chinese opera in a performance created especially for this meeting, based on her recent installation-opera Paradise Interrupted, composed in collaboration with artists Ron Jean-Gilles and Guillermo Aceved; Umashankar Mandravadi's introduction to his investigation into the acoustics of archaeological space; and Amina Ahmed's interest in a universal humanity, as explored through the language of abstraction.

In keeping with the spirit of Field Meeting 4, I wanted to first share how I see my own practice; something I rarely talk about, given the fact that I am, aside from being a writer, editor, and at-times educator, an artist who – as one colleague describes it – decided to go undercover; a decision I made when I realised that my goal was to take the art world itself as my subject, which lead me to writing as my medium of choice. And by 'art world', I mean the global network that makes up a global, culture industry made up of museums, galleries, art fairs, biennials, auction houses, studios, artists, dealers, curators, and so on: nodes, sites, and agents that form contemporary art's trans-global public sphere. It is in this world that I have been able to think about issues of hybridity, history, and questions of global – and post-western – solidarity in the 21st century through a series of overlapping frames, one of which is globalization, its relationship to western modernity, and its manifestations across a postcolonial, post-Bandung world.

Within this study, which I see as fieldwork, writing is a material discipline not unlike painting or sculpture, in which words become tones in a palette. In fact, when it comes to the relationship I have with my work, I think of two things. The first is the literati tradition in pre-revolutionary China, when painting was often a deeply reclusive and personal act for scholar-bureaucrats. The second is a section in Plato's Phaedrus, when Socrates describes a good text as a live body; at one point, Socrates actually talks about his own body as a vessel through which words pour in from some unknown – or forgotten – source.

The notion of writing as a live body, evolving, reactive, and changeable, is the perfect way for me to understand not only my practice, but the questions I consider within it, related as they are to the cultural politics of the art world, as fragmented, transitory, global, and historical, as it is. And I am under no pretence that this world is innocent of the contradictions that characterize our times. In fact, it is one of the ultimate sites to study those very contradictions: an engine of a problematic (and at times neo-colonial) process of globalization that is affecting us all, whether we know it or not. Within this process, I am at once an active, passive, and complicit participant, and my study has become the practice itself – predicated on experiencing, observing, and at times submitting to the forces of global politics from within the privileged and contentious space of culture, so that I might make modest attempts at representing what I see.

All of which brings me to what I have been asked to do: offer some kind of conclusion to what has been discussed over these past two days.

The task is daunting, because it is ultimately an act of representation. I thought about this when watching Heba Y. Amin's presentation, The General's Stork, which considered the new norm in representational perspective, facilitated by surveillance technology associated with the military industrial complex, and by association the narrative of imperialism. Taking an event in 2013 – 'when Egyptian authorities detained a migratory stork traveling from Israel to Egypt because of an electronic device attached to its leg' – as a starting point, Amin's tale included a reminder of how the phrase 'bird's eye view' came into being: when the German army trained pigeons to carry cameras on their legs in the early 20th century. The story links 'the detached and observant gaze of … the aerial view' with 'the language of occupation and colonization' that 'has been written into the visualization of landscape'. Somehow, I equated this with my own position as a writer trying to capture an all-encompassing view, in this case of Field Meeting 4.

But of course, this is how it always begins: that is, representing complexity, which might explain why Michael Joo ended his presentation of recent projects with the Sharjah Biennial in the UAE and EVA International in Limerick, Ireland, with a number of parting questions. These included:

How to pose questions of place and location that are so overwritten by generations of trauma or conflict over that very place's identity? What are the alternatives to synthesis, homogenization, unification and assimilation? Can there be simultaneous, pluralistic viewpoints?

I believe these are questions we are all asking ourselves in this room, no less in the frame of Field Meeting 4 itself, curated as a gathering in which we have all been invited to be vulnerable together and share our experiences of thinking through the world as we know, see, and feel it. For Amin, the task is about weaving history's many multiplicities into a meaningful story. In the case of Ho Tzu Nyen, whose presentation explored the intersecting histories and beliefs that cross through the body of the Malayan tiger, it is about using fragments – his own presentation was composed of nine – to reach out to a bigger whole, so that history might be opened up to other forms of life, narratives, and broader ecological questions. Likewise, Nora Razian described her work as director at the Sursock Museum, particularly through recent exhibition Let's Talk About The Weather, through the task of binding the history of the institution with the history of the city of Beirut itself, in order to create a true public space.

The reason we all do it – that is, try to create spaces for pluralistic perspectives – appears to be one and the same. As Shezad Dawood put it when presenting his research into Kalimpong, 'a small town in West Bengal, at the foothills of the Himalayas, and the entry point to Tibet' once known as a 'nest of spies' and 'where esotericist Alexandra David-Neel first met the Dalai Lama' – each layer has layers, the fact is almost a given. Thus, 'why have only a singular rabbit role?' After all, so much of what we do is about making these rabbit holes – be they gaps, absences, portals, or presences – not only visible but tangible.

I relate to this deeply as a writer: because every word is a rabbit hole the minute you try to put thoughts into sentences that might somehow articulate what it is you want to say. And there is a trap in trying to grasp any totality, which one might call any attempt at representation. The more we go in, the more fragmented the whole becomes. If we try to contain that fragmentation too much, the expression becomes rigid rather than live and discursive. To strike the balance is part of the process, which in many ways defines the practice itself. This is something Jonas Staal has developed in the New World Summit, as we saw in a presentation outlining a discursive space that has been meticulously designed and developed to offer a framework through which pluralism might exist by creating the conditions in which relations – even if they are rooted in difference – become the common ground upon which we might truly hear and see one another. As Staal himself asks: 'how do places like Catalonia, the Basque Country, Kurdistan, Baluchistan, Azawad, West-Papua, and the Aboriginal Nations enter into an art practice?' The answer lies in the formalism behind the project through which Staal attempts to answer the very question he poses.

In this regard, borrowing Michael Joo's words, the form 'becomes a doorway that makes us vulnerable', so that we might lay it all out, just as we are doing here. The efficacy of such formalism is palpable, too, in the way Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme have honed a formal compositional language that tempers a very specific urgency and intensity so that a threshold of universality might be created from real struggles to which our connection has been severed, or blocked, and those who have been made absent are brought into presence. One might argue this is the role of art: to make things visible, or offer ways through which connections are made. As artist Wafaa Bilal put it: 'the role of the artist is to act as a mirror reflecting social or political conditions.' Or, as Mary Ellen Carroll said: 'the work of art is successful if it makes us aware of our own existence.'

And yet, it seems that even this success – of creating a mirror through which anyone might find a reflection of themselves, or the world around them – can sometimes and unintentionally harden the walls of the echo chamber the art world can so often be. Particularly now, at a time when, as Asia Society Director Boon Hui Tan noted in his opening remarks on the second day, 'we are seeing the rise of regimes bent on driving people into tribalist containers'. This is a phenomenon that the art world must resist, particularly when thinking about the global condition so many of us embody within it, be it through history, circumstance, or choice – that is, of belonging to multiple worlds and inhabiting different spaces at once.

Thus, it is no surprise that the question of the art world's elitism was raised throughout this meeting, given recent political events. Curator Xiaoyu Weng – in conversation with artist Chia En-Jao and photographer Xyza Cruz Bacani regarding projects with migrant domestic workers – asked how we might do away with art world jargon in order to speak to, or become effective for, other groups within society. Comedienne Suzie Afridi, in a panel discussion that followed her comedy performance staged in collaboration with Wafaa Bilal, put it pretty bluntly when she suggested that Trump might have won because art's high-minded esotericism – as commendable as it so often is – can in fact alienate rather than include a wider audience. On the second day of this meeting, we heard of ways practitioners are responding to the challenge. These include Mori Art Museum Chief Curator Mami Kataoka's presentation on what she calls 'total curating', in which Kataoka presented projects geared towards speaking to a wider, and broader, audience; and artist Ye Funa's beautiful articulation of a practice rooted in breaking boundaries between the exhibition space and the space of daily life.

This desire to reach out, make connections, and transcend or transgress boundaries and current divisions speaks to the need for gatherings like this: as Boon Hui Tan described it, 'more a communion than a conference', in which empathy might be practiced in earnest and for a multitude of different reasons, from uncovering forgotten stories, writing parallel narratives, filling in knowledge gaps, dealing with trauma, proposing new perspectives, or simply posing questions such as those Yasmin Jahan Napur asked while making roti from scratch on stage, like: 'who are you?' 'where do you come from?' and 'are you angry?'

In this regard, Leeza Ahmady's invitation for us to speak together about what practice means in simple and direct ways feels vital. I think what she means is that we speak with sincerity and conviction, be it with humour and/or with formal precision. As Anthony Lee noted, words cast spells, and as Heba Y. Amin said: 'the fictions we tell can become powerful truths in the world'. It feels like the time has come for us to think again about how the potency of our work might act in a world beyond our own. This is where the bridge comes in, which the Guggenheim's Director of Public Programs, Cristina Yang, mentioned in her opening remarks on the first day using Homi K. Bhahba's introduction to The Location of Culture as a reference. Here, the boundary is described as the place where something begins its presencing, and where the bridge, quoting Heidegger, 'gathers as the passage that crosses'.

This brings me to what I have read practice to be, based on the meeting we have participated in. At one point during the first day's first panel, art historian Clare Davies wondered if what we were seeing in Field Meeting 4's programme was not so much 'thinking practice' as 'practicing', with 'the former implying a certain remove'. To this I would respond that practice is the process of thinking: what Leeza Ahmady described during her introduction as the journey we each take as we move through – and in – the world, filtering it through the lenses and membranes of our bodies, brains, hearts, and souls. As artist David Richeson said of his own definition: 'awareness, aliveness, consciousness, every day: that for me is the practice.' In this light, the work becomes the manifestation of the practice – and this thinking – as it progresses: a bridge between the real, the maker, and the representation, for which the thought becomes the water, the channel, the wave; the energy that keeps on moving.

Or, we could go for another analogy: that if practice is the pursuit of manifesting our thoughts, the objects these thoughts produce are the formal signposts marking the way-finding cartographies (or anti-cartographies) of bodies out in the field, constantly reaching out not only for each other, but for the unknowable void – the edge, the beyond, the transgression, the transcendence, or as Michael Joo put it, the 'limitless space', where new possibilities, new imaginations, new configurations, and, as curator Erin Gleeson described it, 'the expression of new vernaculars', are waiting to emerge.

We have seen this space being produced throughout this meeting, no less in the final panel, when artists Khalil Joreige, Joana Hadjithomas, Rashid Rana and Ho Rui An were all united by one thing: the way art as an expansive field continues to offer us the tools by which we might interrogate the peculiarities of our present, take history and the future into our own hands, and counter – or uncover – official representations and sanctioned meta-narratives, so that we might consider how to engage with a world to which we all ultimately belong.

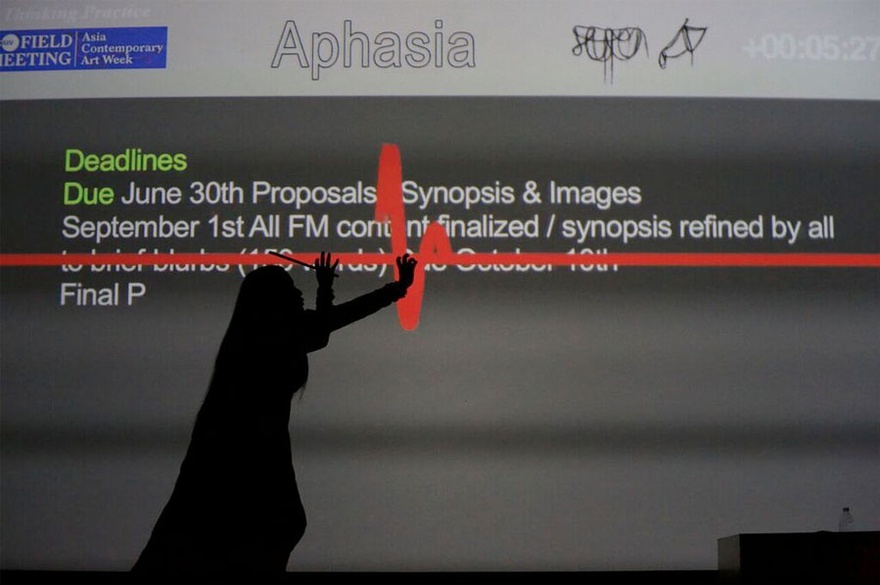

But while such expansive spaces as the one we are in now are formed through the intricate exchanges that art can so often mediate, these exchanges do not presuppose a unity in which we come together as a congealed 'one'. Rather, these are sites of active contradiction, in which we are allowed to not only be who we are in all our complexity, but share our knowledge along the way in encounters like this – without fear, in solidarity, and across languages, be it poetic, in the case of Raha Raissnia's evocatively silent presentation, in which images were followed by a single poem; performative, as in the case of T-Yong Chung and Loo Zihan's contributions, the former involving a video of the artist working on a self-portrait that he inevitably subverts both on celluloid and on stage; and non-sensical, as Mithu Sen exemplified on both days, when she presented Field Meeting emails themselves on a screen, and thus turned the requirements behind the performance into the performance itself, necessarily reminding us all of just how absurd – and constructed – such gatherings can be.

So what does this all mean? Clare Davies asked as much when she raised the following questions on the first panel of the first day, which I will quote in full:

If practice is something you have to do, a thing you do because you do it, how does that connect to the politics of the work that is implicit in each case? What does it mean to practice in a moment like this, or propose different ideas of legibility and communication?

To this I would say: it means everything, insofar as it means something to each of us in this room.

Stephanie Bailey

New York, 12 November, 2016.