Reviews

The Revolution Will Not Be Online

33rpm and a Few Seconds by Rabih Mroué and Lina Saneh

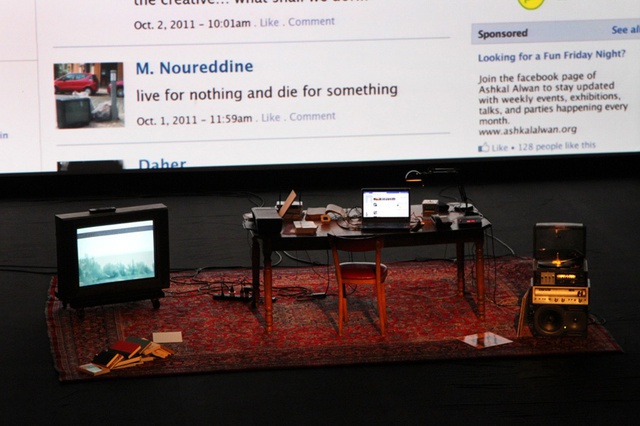

Rabih Mroué and Lina Saneh presented their stage collaboration 33rpm and a Few Seconds (2013) at Asia Society’s theatre in New York on 29 and 30 April 2014. The play, void of stage actors, consisted of a projection screen, laptop, fax machine, TV, and a record player performing as the narrators that broadcast the story of the fictional Diyaa Yamout, a Lebanese activist who has committed suicide. The various media props run perfectly on cue and play out the tragedy whereby the suffering protagonist kills himself for a cause and leaves behind others that continue the suffering after him.

According to the artists, the plot alludes to the suicide of Nour Merheb, a young activist who protested Lebanon’s legal system and fought for reforming its government to a secular one. Here, Yamout’s death is the catalyst to a string of posts on his Facebook newsfeed that begin with disbelief and denial of his demise, to arguments on the religious taboos of suicide, to the politics of Lebanon, its social infrastructure, and finally forced acceptance of his death. The play seems like a reflection on the current state of politics and activism in Lebanon, but more importantly, the play uses this highly mediated event to reflect on the stability of virtual space and the ethics of public and private in social media. Along with assisting the audience in piecing together the details of the suicide, the spewing out of information shows the ongoing disengagement of media from the actual event.

With Yamout’s sudden departure, we sit in the darkened theatre, as though at the edges of his living room, which makes for an eerie feeling that Yamout could have killed himself in this very room. We witness the community’s reaction by way of social media. The stage props come to life one after the other: music plays off a record player, the laptop on the workstation displays the internet browser projected on a large screen before us detailing the activity on Yamout’s Facebook page. His name, Diyaa Yamout, leaves one pondering on the artists’ purposeful selection, as it translates from Arabic to something like brightness dies.

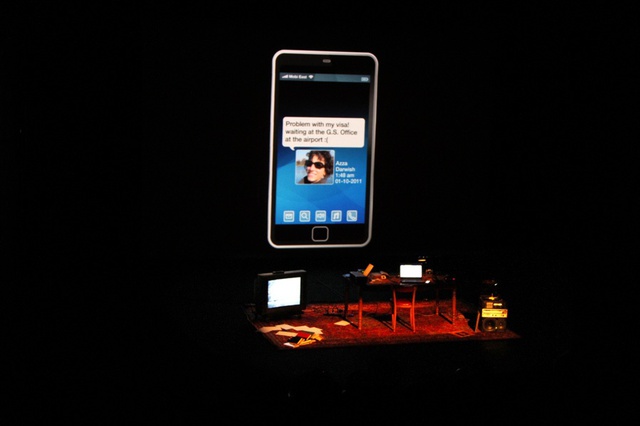

The wall is updated with posts from friends. While many are surprised, grieving, or shocked by his death, others point the finger at religion and social taboo, and most argue that the reason for his suicide was ‘the cause’. While it is unclear why he took his own life, Yamout did express in his farewell note that his action was not politically motivated. Nevertheless, it becomes apparent that the community needs a reason and an image for the unnamed revolution debated on Facebook. The posts, links, and arguments, channels flipping on the TV, text messages buzzing, and answering machine messages appear to survey the ‘current’ political landscape of Yamout’s Lebanon. What emerges is a commentary on the disengagement with Yamout’s death and of the media itself. This sense of detachment is made visible via the constant updates on the wall that force older posts to become submerged below the frame of the screen. The feed relentlessly keeps updating and to trace the story one would have to scroll down to whenever it began in order to recall valuable information hidden in the information flood.

There is a sense for a need to patch together some sort of linear narrative through the endless trail of posts, messages and comments. However, a resolution is never achieved and things are forgotten as soon as something new pops up. Facebook chatter is exposed as both pointless and urgent, ultimately a waste of time in an intangible and non-committal space. The only emphatic voice in this media frenzy is of the woman on the answering machine, Yamout’s lover. Her calls are unanswered. She leaves pleading messages to meet with him and talk, yet it feels as though she knows it is too late. She carries on speaking to him as though he were at his desk listening. She finishes off one message with, ‘Who has the right to decide who is dead and who is alive?’

Towards the end of the hour-long play, The Revolution Will Not Be Televised by Gil Scott-Heron plays from the stage – an uncompromising critical song that came out of the political situation of the African-American Civil Rights movement. The song urges people to unplug from the TV that will never broadcast the ‘pigs’ beating up ‘brothers’ on the streets. It warns that complacency, media, and a capitalist society are not the path. Scott’s repeating lyrics tell us that the revolution will not be televised amongst the slew of white-washed commercials and sanitized media of the 1970s, bringing our attention back to the stage activity: the virtual debates, ads on the side bar of his Facebook page for 98 weeks and the Arab Image Foundation, his ‘likes’, posts by his virtual friends hypothesizing reasons for his death and the current state of society. This all embeds us deeper into the swell of media transmissions. Ultimately, the revolution exists beyond the filtered pepsi-cola stream of television, and 33 rpm and a Few Seconds emphasizes this with the constant ringing, beeping, buzzing, posting, and TV channel flipping, revealing the disengagement with the actuality.

While revolutions are currently transmitted on our TVs, laptops, and smartphones, the struggle remains a distant one that cannot be accessed remotely. And, when the noise of political propaganda, theories about Yamout’s death, and religion drive the conversation, the scenario conveys a disengagement with Yamout. His Facebook wall becomes the platform for futile debate. When Scott-Heron ends with ‘the revolution will be live’ it can be perceived, in this context, as live-stream on social media that is disseminating the news of Yamout’s death, political conflict, and societal upheaval. Yet it remains disconnected – no matter how rapidly the news spreads – amongst the multiplicity, contradictions, and deviance from the instigator. It is Yamout that weaves in and out of the narrative, while at the forefront is political and social crisis, lack of resolution, and a community in disagreement and turmoil.

Oddly though, the play ends with a crescendo of music, the phone rings, a text message arrives, Yamout’s voice on the answering machine asks to be left a message and his lover’s final words are ‘…I need a different end, an end that will be just for me. You’re so stubborn, you forced us to face the fact that you didn’t leave us any choice. I hope that you’re happy now. Good night.’ The TV monitor plays Janis Joplin’s cover of Summertime and a bird glides in the blue sky. For a desperate unresolved situation, 33 rpm and a Few Seconds left quite a resolved and tidy finale. Or, is this a comment from Mroué and Saneh on uncommitted contemporary culture? Will it pick back up on the revolution when the easy living of summertime is over?