Reviews

Unedited History, Iran 1960–2014

A Recourse to the Past

Unedited History, an expansive show charting 50 years of visual culture in Iran through some 200 art works and 26 artists, invited visitors to contemplate the disruption and disjuncture in the modern history of Iran. Outlined at the beginning of the exhibition, the curators – Catherine David, Morad Montazami, Odile Burluraux, Vali Mahlouji and Narmine Sadeg – sought to contribute to current research on the emergence of modernism in Iran, most recently realized in the Iran Modern exhibition at Asia Society, New York, last year. Their focus, however, was not what distinguishes modernist expression in Iran from dominant modes in the western world, but rather to uncover the connections across time periods and dispute the notion that the birth of the Islamic Republic of Iran destroyed the course of modernism. Taking a critical stance to avoid clichés of art that is market driven, the curators explained in the exhibition text: 'we need to approach the subject without reference to investment or the effects of fashion, both of which are part of "contemporary Iranian art" and can lead artists, institutions and the art market to invent and exploit their own exoticism.'

Organized into three distinct sections, like chapters in a text on Iranian history, the exhibition proposed connections between ideological, vernacular and artistic modes of production from film, photography, painting, graphic arts, cartoons and installation, presenting a certain heterogeneity and multiplicity in form, but drew these out across historical junctures. This charted timeline began in 1960 with Minotaur (1966) by Bahman Mohassess, a figurative painting of the classic Greek mythological character. Unconcerned with incorporating cultural signifiers in his work, a preoccupation with identity of many of his contemporaries, his personal rendering of the classic mythic figure is as comic as it is disturbed.

After the first room, the exhibition space divided into smaller sections that housed collections of archive material. Parviz Kimiavi, a filmmaker who was sidelined both before and after the revolution because of his experimental style and provocative subject matter, recut his entire filmography (Oh, The Protector of the Gazelle, 1970; P Like Pelican, 1972; The Mongols, 1973; The Garden of Stones, 1976; O.K. Mister, 1979; The Old Man and his Stone Garden, 2004) into a stand out five-channel installation. Presented together, the films communicated with one another – in O.K. Mister, Cinderella climbs down a set of stairs on one screen, for instance, while an old man heralds the discovery of oil in another. In the vein of Jean Rouch's ethno-fiction, where lines between reality and fantasy are blurred and never clarified, the installation produced a commentary on the Shah's rampant modernization policies, which left Kimiavi's characters confused as they come to terms with rapid transformations in their towns and villages.

In the adjacent space, an ongoing curatorial project by Vali Mahlouji entitled Archaeology of the Final Decade juxtaposed two immense archives against one another. The first collection is ephemera from the Shiraz Arts Festival – an ambitious global platform for the performing arts that ran from 1967-1977 in the southern city of Shiraz and the ancient ruin of Persepolis – in the form of programmes, posters, scripts and documentation of performances such as KA MOUNTAIN AND GUARDenia TERRACE (1972), a theatre piece directed by Robert Wilson that lasted seven days, and the Legong Kraton Dance (1969) – a traditional Balinese dance and gamelan drum ensemble. Cumulatively, the materials articulated the role of the festival in putting forward experimental modes of avant-garde expression, while enlivening culture clashes between radically different performance genres. Yet, despite the wealth of documentation, the information on the festival audience was conspicuously excluded here, perhaps inferring the festival organizers' disregard for how the festival was received inside Iran.

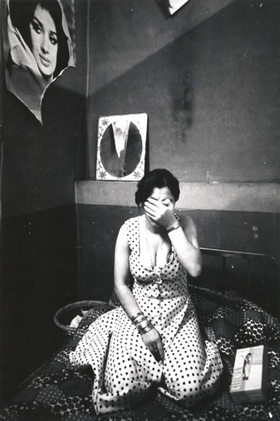

In stark contrast to this festival archive, the next room exhibited Kaveh Golestan's infamous series of dignified portraits of the prostitutes of Shahr-e No, a citadel in the south of Tehran which has since been destroyed. The photo series was produced in 1975-1977 and last exhibited in its entirety in 1978, and depicts a very human face of the poverty in South Tehran. Making palpable the class divisions that spurned the revolution, the images reveal those left behind by the cosmopolitan aspirations of the monarchy, represented in the archive of the experimental Shiraz Arts Festival in the previous room. As such, the contrast of these two archives provided a sociocultural framework for the oncoming revolution while reincorporating this rarely exhibited material into Iranian cultural history.

The exhibition's second chapter offered various visual manifestations that chart the revolution of 1979 and the eight-year war with Iraq that followed, thus contrasting the vast differences between the aesthetic regime of the Islamic Republic of Iran with the previous era. Never before seen footage of the anti-shah demonstrations captured by documentarian Kamran Shirdel was on display in its entirety: a sort of disordered chronology of various fields of activity from poster-making to mass rallies. The Sacred Defence cinema of the Islamic Republic is acknowledged in the series Haqiqat (Truth, 1980-81) by Morteza Avini, presented on two screens. His films of the war front were key in creating subjective accounts of soldiers and martyrdom and cementing the aesthetic schema of the new regime. Bahman Jalali's photos of interiors destroyed by the eight year war with Iraq – as humorous as they were bleak – presented images of leaders of the revolution stencilled onto a wall where a prior hand-painted notice read: 'No Smoking'.

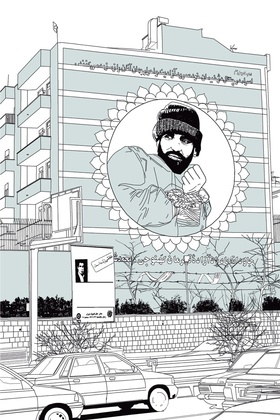

Dedicated to the contemporary period marked by the end of the Iran-Iraq war in 1988, the final section of the exhibition affirmed a number of artistic continuities presented in the previous sections. This was most visible in Mitra Farahani's giant charcoal drawings of beheaded soldiers and Arash Hanaei's Capital (2009), computer generated drawings of Tehran cityscapes. A body of work that draws on the similarities between paintings of martyrs that adorn Tehran streets with advertising billboards, it is in these images that past and present visual cultures clash and ideological messages are diminished. Meanwhile, Chohreh Feyzdjou's vast installation – an assemblage of a startling number of rancid items covered in black polish as if left to gather dust and fester over years – appeared in the context of this exhibition as a commentary on the state of Iran and the condition of its inhabitants, expressed in the artist's own attempt to hold onto something solid: the stamp of her name was visible on each blackened item presented here.

A vigorously researched exhibition, Unedited History provides few moments of levity, particularly in the final section of the show, where black and white photography dominated in works by students of Bahman Jalali. Though they echoed Jalali's practices of careful documentation, demonstrated in his photo series in the previous section, the differences in content and focus of the younger generation are clear: a slide show capturing ten years of family life by Mazdak Ayari bears an intimate view of quotidian life in Tehran, while Khosrow Khorshidi's series Good Old Days (2009-2011), detailed drawings of now-vanished locations in Tehran, echo a constant recourse to the past; a nostalgia that seeps in. Yet in avoiding works that constitute 'contemporary Iranian art', the diversity of expression made apparent in the earlier sections of the exhibition, such as the irreverence of Parvis Kimiavi's films is subsumed by art works that respond to present and past conditions with melancholy and a tinge of ennui.

In all, working against an authorial impulse, the five curators produced an exhibition that felt – through the sheer volume of material – both raw and comprehensive in its cataloguing of multiple modes of visual representation. Yet the display of 'unedited' bodies of work diverted attention from curatorial lacunae. Here, connections between France and Iran were subtly made; many of the artists exhibited had either lived or been educated in France, but this significance was left unexplained. Nevertheless, there has been a fascination with Iran from French institutions as evidenced by recent exhibitions in Paris, such as 165 Years of Iranian Photography at Quai Branly in 2009, and a focus on Iran at Paris Photo (curated by Catherine David) the same year. Unedited History at the Musee D'Art Moderne De La Ville De Paris, a museum funded by the city of Paris, not only reaffirms this interest in Iranian culture, but also heralds a moment at which Iranian image making is contextualized within historical processes rather than being reduced to them, since issues of identity that plague so many group shows of Iranian art are avoided. Rather, the responses by artists to the social and political structures in which they were embedded were exhibited – both critically and compliantly.

Unedited History was on show at the Musee D'Art Moderne De La Ville De Paris from 16 May to 24 August 2014.