Essays

Tracing Dissent at the Margins of Empire

Pan-Kaffirism in Iraq, South Africa, and Sri Lanka

This paper is part of the research project 'The Pan-Arab Hangover', which focuses on the lingering ruins of Arab nationalism and how it plays out in the region's contemporary cultural production. It looks at Arabism's parent ideologies – notably German romanticism and idealism – and how 'unified Arabism' in art, culture, and writing is held up as a potential 'cure' to the region's problems.

The research's larger objective is to dismantle constructions of Arabism, and locate identities erased by Arab-Islamic supremacy, such as Afro-Arabness to minority resistances (Kurdish/Amazigh) and Ajami histories. Under this, we found the word kaffir, or Kaffirism, popping up in strange and seemingly unrelated ways: in the Arabian Peninsula in the ninth century, in Southern Africa from about the fourteenth century, and in Sri Lanka.

***

871 AD. Basra in South Iraq has been taken over by rebels and is pillaged, burned, and devastated. Free Arab woman are captured by former slaves, and auctioned depending on their lineage and line of faith. Many are sold as concubines at low prices. This will become one of history's most vengeful retaliations by the oppressed against their former oppressors. This is the site of the Zanj Rebellion against the Abbasid Caliphate.[1]

Although we now remember the Abbasid Empire as the 'Golden Age' of Islam, it was also a period of great inequality. Growing advancements in agriculture saw increasing technologies of social suppression and economic exploitation, with many slaves brought in. The flourishing of Islamic power in the Abbasid capital of Baghdad, resulted in the erasure of multiple marginal Muslim and non-Muslim identities. The Abbasids' power and wealth was mainly derived from discriminating against non-Arabs. It's worth noting that 'Arab' was very tightly defined at the time, referring only to blood descendants of the nobility, such as the Quraysh, who were given extensive administrative powers and economic resources, resulting in the Arabization of areas outside the Peninsula.[2]

The rebellion began a few years prior in 869 AD, when Ali ibn Muhammad, otherwise known as Sahib al-Zanj declared 'God is great, God is great, there is no God but God, there is no arbitration except by God.' It was a war cry that had been popularized by the Kharajites, or the 'Outsiders', a short-lived community that considered themselves neither Sunni nor Shia'. They are remembered for their aggressive approach to takfir, in which anyone who didn't share their beliefs was branded a kaffir and sentenced to death. Ali had initially tried to incite a rebellion in the 860s against the Abbasid caliphate in Bahrain – where sectarian dissent was already widespread – and pretended to be Shiite leader. Although he grew to be influential as a voice against the Caliphate's administration, his attempts at rebellion in Bahrain eventually failed.[3]

Not far from the sites of the failed rebellion were the Qarmatians, also called 'those who wrote in small letters.'[4] Radically egalitarian and unusually for the time vegetarian – they were also known as Al-Baqaliya, or the greengrocers. Inspired by the success of the Zanj Rebellion, they attempted to establish a utopian republic in 899. Today, they are best remembered for their own revolt against the Abbasids, in which they managed to steal the Black Stone of the Ka'aba – before selling it back to them, and desecrating the Well of Zamzam with corpses.[5]

***

Upon hearing about an outbreak of hostilities between two Turkish regiments in Basra, Ali moved there to try his luck in 868. Many of his devotees from the peninsula followed, and his cause soon swelled to include the black slaves who were working in Basra's salt mines and marshes. In 869, they began to raid the surrounding towns and villages: Arab slavemaster houses were confiscated, their women enslaved, their slaves freed, and their weapons and horses liberated. The Zanj Rebellion ended up recruiting from a wide range of people subjugated under Abbasid Arab-ness – craftspeople, the poor, and most importantly, Bedouins; the involvement of the latter became crucial in controlling many land parcels of the south.[6]

The rebellion's main goal – to take over the port city of Basra and have a chokehold on sea trade – was achieved in 871. After the city was taken, the rebels seized the south and created a capital known as 'Al-Mukhtara', meaning 'The Elect'.[7] The rebellion held for about nine years, aided by the construction of impenetrable fortresses, cocooned inside layers of water canals. Yet governance within Al-Mukhtara was poor, leading to a famine where people reportedly ate mice, dogs, and even their own dead.[8] The community, which ended up reproducing the same deprivations that led to the rebellion, including slavery, began to break down. In 881, the Abbasids, no longer distracted by the Saffarid uprising in Persia, surrounded Al-Mukhtara, captured Ali, and the revolt ended. The Caliphate was ruthless in its punishment, where many of the captured were brutally amputated, or had their throats slit. Ali wasn't spared.

Some historians, such as Ghada Hashem Talhami, have stated that the rebellion should not be sensationalized as a 'slave rebellion'.[9] Unlike the Haitian revolution, the movement wasn't targeting the institution of slavery. Most of those fighting in the rebellion weren't even slaves, but came from a range of communities alienated by the ruling classes – who would be collectively punished if they acted, and oppressed if they didn't.

Today, the Zanj rebellion is sometimes dubbed the 'Negro Rebellion', a consequence of Orientalist accounts that flattened the participants as all being from the Swahili or Zanj coast, and therefore black. Trade records, however, reveal that most of the slave trade of that period trafficked in Arab, Desi, and Southern European bodies. In the 800s, Arab trade with East Africa was mainly made up of exploited resources and minerals, while the African slave trade in the Indian Ocean didn't start until several centuries later.[10]

Ali's own lineage and ethnicity is another grey area. He claimed to be a descendant of Ali bin Abi Talib, but most people around him rejected the claim. Historic sources also disagree on whether he was of Persian or Arab origin. Although it is agreed that his parents were free, his paternal grandparents were both slaves to Arab masters, and his paternal grandmother was a Sindhi woman.

This is where it begins to get interesting: References to the grandmother emerge some 50 years after the rebellion was crushed. Some sources refer to her as Kali al-Qaramati, and paint her as a freed Qarmatian woman who campaigned against slavery, and she would later become an emblem of the revolt. Others call Ali's grandmother Kali bint Junoob al-Kapisi, or Kali bint Kaffir. We found that Kapis is the historic Sanskrit name of a region in Afghanistan, which the Persians dubbed 'Kaffiristan', due to their polytheistic pagan culture. After it was Islamicized in the 1890s its name was changed, rather appropriately, to Nuristan and today most refer to this group as the Kalash. Was Kali from Bahrain, Sindh, or Afghanistan?

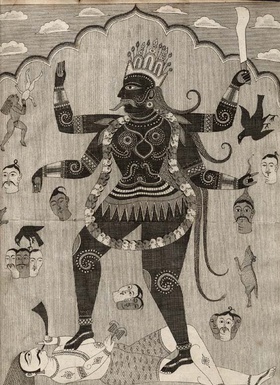

Her first name is intriguing too – is she linked to Sara e Kali, the Black Madonna of the Romani? Kali the Hindu goddess of death and destruction? Or was she Jewish – 'kale' means faithful in Hebrew –[11] and thus dubbed a kaffir?

***

The word 'kaffir', in its many usages and meanings, is quite a loaded term. In Islam, it refers to the infidel, while in South Africa it was a colonial term used to refer to black people. Today the 'k-word' as it has come to be called there, is a racial slur that still carries memories of the violence committed towards blacks under apartheid. Think of Kwaito musician Arthur Mafokate's song Kaffir (1995) where his lyrics protest against his 'Baas' or 'Boss' – the white employer – use of the word to refer to his employee.

Kaffir originates from a Semitic word K-F-R, referring to Jewish farmers who 'covered seeds'.[12] The Muslim deployment of the word assigns it to infidels or unbelievers, and more poetically, to 'those who cover or conceal themselves from the truth',[13] the truth being Islam and belief in the prophet Muhammad. The analogous speech act of takfir is a verbalization of this othering. Kaffir was initially used by Arabs to designate otherness, as a way to mark anything outside their definitions of Arab-ness and Islam.

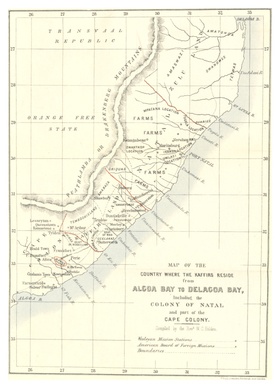

Although the term became associated with Dutch and British colonizers in southern Africa, the term kaffir is suffused with a history of trans-Indian ocean relations which long predates the European trespassers. Arabs from the peninsula are believed to have mobilized the term when colonizing the Maghreb, going on to apply it indiscriminately across the continent. Some sources also trace kaffir's marking of blackness to East African Muslims, who applied the terms 'kaffir' or the Swahili 'Kufuru' to Africans of the Cape. The word was eventually appropriated by Europeans to refer to the non-Christian inhabitants of Southern Africa, and kaffir would later become one of the fundamental constructs of South African apartheid.

For the Europeans, though, the word soon diverged from religion to become a blanket justification for settler colonialism. To brand something kaffir was to disparage it as savage and uncivilized, therefore clearing the slate for a new European beginning. Ironically, Muslims who were captured from both East Africa and the Malay Peninsula became kaffirs in South Africa. Kaffir also came to connote 'low' or 'uncivilized' behaviours: when something deteriorated, it had 'gone to the kaffirs', while unpunctuality was dubbed 'a kaffir sense of time', and so on. A shortened version, 'kaff' has some currency in South African slang today, used in a similar way to 'ratchet' in the USA.

Kaffirism, more broadly, came to refer to the circulation of goods and people between the Indian and Atlantic Oceans in which South Africa was a component, if not the major node. In addition to people, indigenous fruits, birds, trees, food, and tools became Kaffirized – think Kaffir lime, Kaffir Beer, and Kaffir Cake. Many of these products are still used today and can be found in cuisines from Haiti to Thailand. On the London Stock Exchange, 'kaffirs' is still used to refer to South African mining shares, especially gold.

Its equivalent in Portuguese and Spanish is the word cafre which gained prominence in South America during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and was used in a similar vein. Cafre, which initially marked blackness in South America, later began to designate the process of subordination of cultural practices, rituals, peoples, and languages. Similarly, Cafrealization was a subcontracted word used to refer to a colonizer's 'adaptation to the tropics'. It also became a major representative of Spanish and Portuguese identities, a cafre could also be someone who is biracial (today referred to as mulattos). The word Kapre in Tagalog refers to a tree demon, and also derives from the word Kaffir. It had initially been used by Arabs and Moors to refer to the 'darker skins', and then later brought to the Philippines via Spanish colonizers. The Kapre mythical figure was mobilized to prevent Filipinos from assisting escaped African slaves.

***

Afrikaans, one of the main languages of South Africa, is generally perceived to be a product of Dutch settlers in the Cape. These settlers, who spoke Dutch among themselves, initially used Afrikaans only to communicate with those who worked for them. Variously called Cape, kitchen, mutilized, broken or uncivilized Dutch, the creolized Afrikaans was seen as the tongue of the lower classes, the kaffir language.

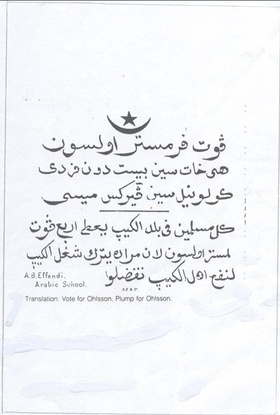

However, Achmat Davids' thesis 'The Afrikaans of the Cape Muslims' in 1991 revealed that the earliest instances of Afrikaans being written down were not in the roman script, but in Arabic. Many of the slaves in South Africa were Muslims from the Indo-Malay Peninsula, Ceylon, South India, Bengal, and the East African coast. In the 1800s, the Ottoman Empire sent a series of envoys to the Cape Colony to build madrasas and educate these Muslims, at the curious request of the British queen, Victoria.[14] These envoys used the Arabic script to begin standardizing the Afrikaans that was the lingua franca at the time; the best known example of this Arabic-Afrikaans is Kurdish scholar Abu Bakr Effendi's 1869 Bayaan al-Din. A polarizing figure, Effendi was hated by many for his declaration that the crayfish much beloved by Cape Muslims was haram, and was even taken to court in 1868 by the kreef (crayfish) party, eventually losing the case.[15] He was also responsible for the introduction of the hijab and the fez in the Cape. These early educational texts written using the Arabic script are believed to have been the first attempts at mapping and writing down the 'lower class' Afrikaans, laying the framework for Afrikaans' subsequent Romanization.

Most of these records have been ignored. The few that have been translated largely either teach Islam or record prosaic memos and market lists. Looking through some of these translated documents, Kali pops up again, in a diary entry by an unknown slave, which said, 'O Kali, spare us the wrath of the whites'.[16] This is the only reference to Kali found, though much still remains to be translated. Who is Kali this time? Is she still held up as some kind of symbol of perseveration under oppression and slavery?

The heritage of the Arabic script in Africa is also an interesting one. Holy men who had converted to Islam around the tenth century in West Africa, began to modify the Arabic script to adapt to local languages, such as Hausa, Wolof, and Fulfulde. This resulted in the Ajami – meaning stranger in Arabic – script, which Africanized the religion and Ajami eventually displaced Arabic as the teaching script. Strong parallels can be drawn to the vernacularization of religion in Europe, in which the Roman script of Latin was modified for writing in French, Portuguese, Hungarian, and other languages. Writing in Ajami, which signalled a more Afro-centric identity, became a mode of anti-imperialist resistance. In short, writing in Ajami was more 'black' than it was 'Arab'.

Today, to be considered literate in West Africa is to write in either the Arabic or Roman scripts. For example, the 50 million Hausa speakers today who read and write only in Ajami are considered illiterate. Ajami scripts – and by extension, the population who use them – haven't been recognized or validated by most scholarship. Most archives written in Ajami are currently labelled 'unreadable Arabic'. Fallou Ngom, one of the few academics looking at this script, believes that through the study of these archives, he will be able to completely rewrite the history of the transatlantic slave trade.

These tensions also extend into linguistic studies of the region where the map of Arabic dialects will mainly consider territories that are part of the Arab League: Egypt, the Levant, Iraq, the Maghreb, the Gulf and Sudan. Yet, other dialects of Arabic of the Sahel region such as Chadian Arabic, or Hassaniya Arabic aren't considered part of this linguistic ethnologue.

***

The instances of kaffir discussed so far have been somewhere on the scale between derogatory to violent. Yet another kaffir group exists in Sri Lanka. They are one of the country's smallest minorities and take great pride in the term. The Sri Lankan kaffirs, cafirinhas, or Afro-Sinhalese, are descendants of Portuguese traders and African slaves, who were brought from South and East Africa as labour and soldiers to fight against the Sinhala kings in the sixteenth century. Like the Afro-Iraqis and Afro-Khaleejis, the Sheedis in Pakistan, and Siddis in India, they are among the world's lesser known Afro-diasporic groups. They speak a dying Creole based on Portuguese and Sinhalese and although they were originally Muslims, today practice Christianity and Buddhism.[17]

Sri Lankan kaffirs are especially known for Baila music, with Baila coming from the Portuguese verb bailar, meaning to dance. It's an old folklore style, which re-emerged into the mainstream in the 60s thanks to Wally Bastian, who is also known as father of Baila. He has a little known single named Kali Cafirinha; while the light-hearted verses talk about the vicissitudes of daily life, the chorus has a particularly haunting refrain – 'O Kali, deliver us from the wrath of the masters'.[18]

Were there actually any links between all these Kaffirist identities? Who was Kali bint Junoob al Kapisi? Did she ever really exist?

This paper was based on a talk presented at Global Art Forum, Art Dubai, March 2014, and revised for publication in Ibraaz.

[1] Ghada Hashem Talhami, 'The Zanj Rebellion Reconsidered,' The International Journal of African Historical Studies 10.3 (1977): pp.443-461.

[2] Abdulla Badawi, 'Rays of Dawnlight Outstreaming from Far Horizons of Logical Reasoning' in Nature, Man, and God in Medieval Islam, eds. E.E Calverley and J.W Pollock (Leiden: Brill, 2002), pp.1001-1009.

[3] Talhami, op cit.

[4] Joseph Saunders, A History of Medieval Islam (London: Roultedge, 1978), p. 130.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Talhami, op cit.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] 'Kale,' My Hebrew Dictionary http://my-hebrew-dictionary.com/list2.htm.

[12] 'Kaffir,' Online Etymological Dictionary http://etymonline.com/index.php?allowed_in_frame=0&search=kaffir&searchmode=none.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Martin Van Bruineessen, Mullas, Sufis and heretics: the role of religion in Kurdish society: Collected Articles (Istanbul: The Isis Press, 2000), pp.133-141.

[15] Ibid.

[16] This is speculative.

[17] S. de Silva Jayasuriya, 'Trading on a Thalassic Network: African Migrations Across the Indian Ocean,' International Social Science Journal 58.188 (2006): pp.215-225.

[18] Again, speculative.