Essays

Living Roundabouts in Bahrain

Five Stages of an Artist Residency

The phenomenon of the international artist residency is embattled. An explicitly temporary arrangement, it offers a context whose depths an artist can only begin to mine. How to produce meaning from such a series of surfaces? How to disrupt the banality of institutionally sanctioned art making, especially amid local and global subjugation? How to seek shared liberation within such a temporary engagement?

International residencies function institutionally, because they might bolster a national image. For example, an American artist resident will elevate the status of an art institution supported by the US Embassy (situated not far from the 'American Area' of Manama). In Manama, an art institution's 'American Room' holds 3D and laser printers, plus 20 or so computers donated by 'the Americans'. I am told that an exhibition of an American artist is mounted (between exhibitions of regional work) because the institution owes the Embassy a favour. But when the national agenda of an international artist residency is at odds with an artist resident's project of aesthetic or cultural research, the institution's uni-directional function is revealed. In such a case, there is no deeper benefit for the artist, except that the residency might increase the artist's sales, or temporarily sustain their practice.

In 2014, I was invited to Bahrain as one of several international artists commissioned to develop a public work for a festival of contemporary art. My work was not granted permission to be completed; whether due to politics, time constraints, or bureaucratic vagaries, I'll never know. However, what I saw in the initial few days of my 40-day stay affects a swift understanding of how art dies, or how it is prevented from materializing at all. As such, I have divided this text into sections based on five stages of fieldwork undergone during my experience in Manama: 'Arriving', 'Soon After Arriving', 'Residing', 'Loving/Dying', and 'Bristling/Revolting'. The pictures accompanying each section were shot in a span of less than 24 hours. Excluding the first image, they span less than half an hour on the third day, quickly determining a perspective that overshadows the rest of my stay in Bahrain.

Arriving

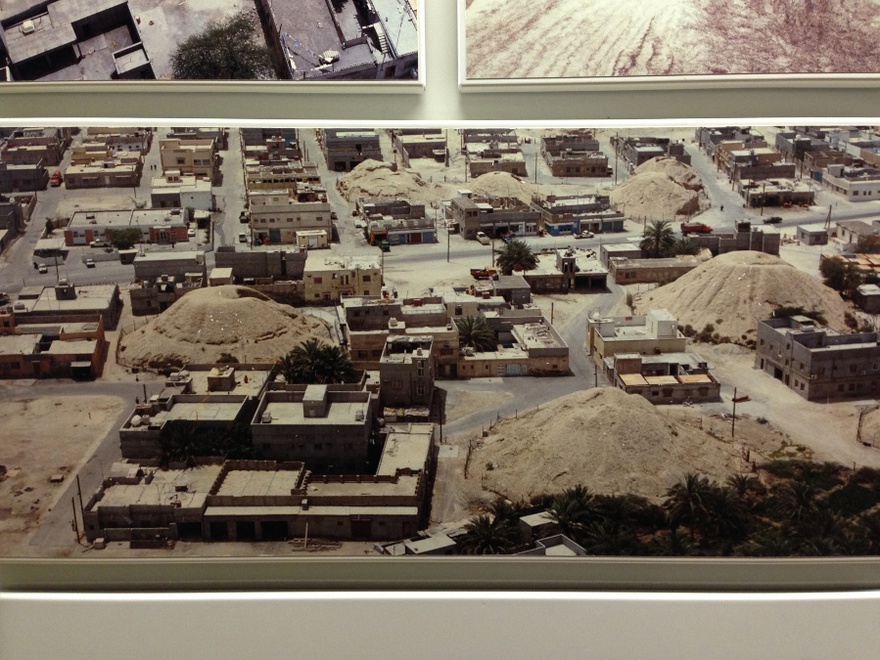

Upon arriving in Manama, I walk along the main highway to reach the National Museum of Bahrain. Upon entering the archaeology wing of the museum, I look at photos on the wall that serve an illustrative function. One photo depicts the working class village of A'ali carefully constructed around several ancient Dilmun burial mounds. Shot from above and a bit laterally, the image is presented inside a rectangular frame. As a viewer of this village in photographic miniature, I hold my camera phone parallel to its surface and touch the button on the screen. This is the first in a sequence of moments captured digitally during the course of my residency, a fairly common research method used by artists today.

Soon after Arriving

The day after seeing A'ali in a picture, I enter the body of the village itself, crossing a series of winding, dusty, inland corridors. A model of all time condenses before me: a half-inside/half-outside space, where primordial sludge turns to industry. That is, where sludge becomes information. A massive avalanche of viscous earth sprawls near rows and rows of just-thrown vessels, which I capture in the rectangular shape of a picture. Humidity is year-round here, and the smell of soft, unformed clay takes easy residence in the sluggish weight of moist oxygen. Just outside: a pallet of air-dried pots. Just a few feet further, a bloc of kilns cancels any residual moisture from batches of upright vessels. A large, neat pile of broken ceramic pieces is stationed close by. An entire production cycle is acknowledged.

Primordial sludge becomes information: pressed, imprinted, manipulated. It is irresistibly supple, perpetually swallowing itself up and spitting itself back out: cannibal fascination. Looking at its ruffled sea-like surface, a rolling, scrolling opaque 'screen' of uneven depth extends before the viewer. Velocity is relative as the shape of the world expands and contracts according to the slightest atmospheric fluctuation within this insurmountable, immeasurable quantity of information. Indeed, such visual quantities accompany the experience very soon after arriving.

Residing

Stepping from one half-inside/half-outside space to another, a small gray truck is parked on the sidewalk, abutting a cross-sectioned, hardened burial mound impressed by shell, shard, and sediment. Cement railing decorated with clay pots attests to the 'local' nature of the surgery. Careful removal of a bothersome half-mound, heritage tumour sliced away, excises past from present, dead from living and, more generally, sect from sect, rich from poor. Inner chambers and ventricles are left exposed, and the view inside the burial mound is weathered and raw.

Monuments like this mound remind me that art dies (or is killed), even as it resides among the living. Art dies variously: when it is repeated in form, exhausting innovation, giving way to mere surface function or skill, or when it is trampled or gagged under oppressive military force. Instead of bulldozing through the mass of earth and afterlife, I envisage a set of roundabouts, each encircling a Dilmun mound. And atop each dignifying, nucleus mound: people are alive, and flashing victory signs.

Today, art and heritage exist as impositions: 'dead space' to be removed or rendered benign. Just as the sea is 'reclaimed', filled with earth to increase the surface area for commercial development, desire (the energy of change) is effaced, replaced by imported security forces. Consider what followed the 14 February 2011 uprising, when the Pearl Roundabout (the Tahrir Square of Manama) was demolished and rendered anonymous, disfigured into an angular, nondescript traffic intersection. Above all, the strange fear of a civil society – citizens with civil demands - supersedes any institutional commitment to cultural transformation. Thus, I observe in my days residing, that art being made in such a climate is largely (with few exceptions) dead – or else geared toward craft, design or commerce.

Loving/Dying

Portraits of loved ones are spray-painted through cardboard stencils onto exterior walls in A'ali's public spaces. From a distance, they call to us, messaging their precise location in Arabic, ana bil douar al lulua (I am at the Pearl Roundabout) or ana fissijin (I am in prison). A picture like this one is always late responding – there is always a photographic delay – but I try to make up for it by absorbing the contours of the loved one's face. I walk the village in search of these portraits, and find a series of public tributes to a partial cast of fallen revolutionaries.

But the martyrs' faces are obstructed from view. Black paint has been hurled against them, leaving public memory ravaged, blocked, suppressed again and again, over layers and layers of attempted resuscitation. The argument we see on these walls is aesthetic and violent. Public grief, mourning and memory are mercilessly quashed by the State. So, death continuously precedes the art act that follows. I am here, outside the capital, in proximal peripheries, and seeing that the most significant and urgent aesthetic activities both rise and fall – come alive and die – on a daily basis. An aesthetic movement continuously regenerating itself has been urgently underway, and has not stopped: just as the notion of revolution continues to advance and recede.

Foreign security forces wield a presence at the heart of conflict, and they are symptomatic of the Kingdom's glaring anxiety; they are uniform overcompensations, there precisely to maintain disparity. As a result, there is symptomatic turmoil in outlying villages. By outfitting the (nonlocal) military with housing, mobility, and authority, and by neglecting sectors of local Bahraini society from visibility or economic security, this special rank of foreign military steps in easy line with a maniacal, over-reactive geometry of oppressive power. There is still urgency in this protracted moment. Foreign artists are not exempt from consciousness in this context of 'practice'.

The subsequent art-act responds to the death of art's afterbirth – artists 'do' residencies with function and purpose unknown, because art is irrelevant inside a militarized state like Bahrain. So, art dies again and again unseen. Any given morning reveals a string of burned walls along major roadways. The same black paint obscuring martyrs' portraits effaces the language of desire; black paint thrown over the words nasr aw mout (victory or death), for instance, gives walls the visual quality of having been torched. But we acknowledge we are alive. We acknowledge that the act of looking is an act of love that pulls meaning from the void of the unknown. Ana mayet (I am dead) says the art-act to the viewer; qatalooni (I was killed). My love and my art died in Bahrain.

Bristling/Revolting

What makes art bristle? Art bristles at the theatre of power, and at military swagger. At men with weapons and god. At the State apparatus. At the nepotism of the 'contemporary'. At death measured in numbers. At global/imperial control of borders. At the established caste system of national identity that determines whether an artist can participate in a residency or not. The 'West' is not really 'West', the 'East' not 'East'. Art bristles at the false pretence of cultural advocacy, at those who distrust artists, who vie in competition with them, or who use them for their own gain. Art bristles at the banality of appropriation and at the banality of art. Art bristles at the wedding of conservative power to the State. At the wedding of art and State. At the wedding party. At the absence of space for inter-class, inter-sex, inter-sect, inter-ethnic utopias. At the obstruction of short and long-term memory, at what happened a few minutes ago and what will happen again very soon. Art bristles at the systematic demolition of cities, and at the killing of 'undesirables' to reduce the demographic threat. At the searing glower from the eyes of a man working for the interior ministry. At the closing of streets for a military parade.

Walking back along the other side of the bisected burial mound, my companion and I find a tear gas canister and projectile, thrown vessels. There is no stamp of origin, but CS gas has been used extensively in Bahrain. It is a chemical weapon that has been used globally to repress civilian unrest. Sadly, there is nothing remarkable or unusual about this image; it is a common enough sight the world over. We are revolting.

How does art revolt? Art revolts by demolishing the system, because the system's project demolishes the integrity of art. Art revolts by rejecting 'practice' because 'practice' has fossilized in the muck of global capital. Art revolts by actively injecting euphoria into hir neurons so the body moves wildly, lovingly, autonomously across borders, all the while inventing new forms of desire and new ways of seeing. We are revolting: on top of the mound, a figure flashes a victory sign. Good morning, we are still alive.