Interviews

Chapters, Records, Keywords

Lucien Samaha in conversation with Walid Raad, Part I

In Part I of this extensive conversation between Walid Raad and Lucien Samaha, Samaha recalls the stirrings of his career as a photographer, which spans some forty years and which has passed through a number of phases and personal life moments, including life as a DJ, a flight attendant, and as a staff member at Eastman Kodak Company. Through this journey, Samaha reveals the range of equipment and programs he has used and mastered as part of his life's work, not to mention techniques he has used to document and collate the plethora of images he has produced. In this, he talks about how he keyword indexes his personal archive, often by inviting friends to go over past images to provide names of those they once knew. In Samaha's explanation of these personal archives, memory and image connect.

Walid Raad: How, when, and why did you start keyword indexing your photographs?

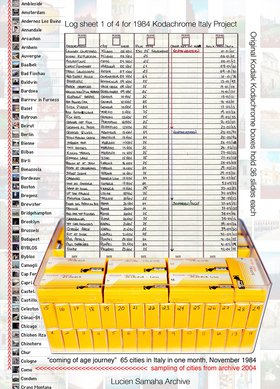

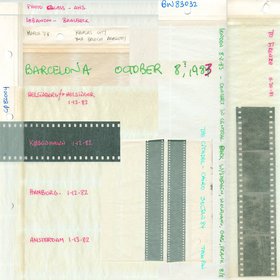

Lucien Samaha: I cut my very first few rolls of self-processed Tri-X film in the early 1970s into strips of six frames and lumped them together into one glassine sleeve. On the sleeve I wrote the date and place, and if people were on the roll, I often wrote the names of the important ones. After perhaps a dozen of those, I discovered the clear plastic holder sheets for individual strips. Once in the files, the sheet could be used to make contact sheets. I transferred my then collection into the new sleeves, along with the information. I was extremely diligent about this process well into the late 1980s when I started my photographic studies at the Rochester Institute of Technology.

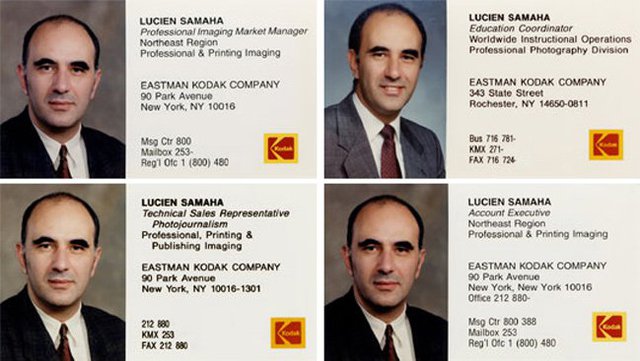

For a variety of reasons – including procrastination – for a period of about seven years I was less organized about labelling my negatives. Another reason was my new career at Eastman Kodak Company, starting around 1990, where I began to use a Day-Timer to log all my appointments, phone calls and activities. At the same time, I had access to unlimited film and film processing. I had simply assumed that I would transfer that information to the negatives at some point. I am now very sorry I hadn't been more organized all along, although it has been a very interesting challenge to go through an investigation exercise looking for dates and events in my logs and receipts, and coupling them with images from the negatives. Fortunately, I have scanned and catalogued all of these negatives, and can go through this process on the computer. Furthermore, it feels sort of important to occasionally use the term 'circa'.

The real serious cataloguing and keywording began in earnest when I left Eastman Kodak Company around 1995. This is when I felt that pursuing photographic interests was no longer a conflict of interest as it was while in the employment of Kodak. (By the way, this concern was self-imposed.) Armed with knowledge I gathered while in the thick of the industry, both from the source (the tech companies I had the privilege of working with) and the users (namely my clients in several industries, but mainly the major newspapers and magazines, and photo stock agencies), I began sorting, scanning, and cataloguing every single negative and slide in my archive. Although this process started 18 years ago and has resulted in a very comprehensive database, it is far from complete.

Just yesterday friends from Denmark in passage from Vermont to Rhode Island stopped by the country house where I am cat-sitting for a couple of weeks. I met them around 1985 in New York City, and then visited them in Aarhus, Denmark, where I took lots of photographs. Last night, I sat them around my laptop and we went through the photographs so that they could give me as many names as possible of their friends in the pictures, and I entered them directly into the database. It was great to see them struggle with their memories in order to come up with the family names of some people they hadn't themselves seen in a very long time. This is a process I do often with friends who come to visit, and I am thinking I should start recording it.

As to why I chose to keyword index the photographs? Very simply, to manage a massive and ever-growing personal archive. For many years, the negatives and slides were accumulating in piles, full of stories and great images that remained latent – pun intended. I wanted to start utilizing them in more conventional ways of sharing – display, exhibitions, and publications, and occasionally to make prints. As the archive grew, it became its own hungry beast that demanded new input every day, whether in photo data or metadata. I had always looked at photography romantically as two different worlds, that of the real world itself, the street, the airport, the party, and so on, and the darkroom, where the photographer can retreat into the negative of the real world, where light is dark and black becomes white. As I gradually weaned myself off the darkroom, the database and its related activities became that retreat.

The keywording itself will never be accomplished, as new concepts are always revealing themselves in newly created or re-visited images. Details that were once insignificant emerge as rallying points for new projects, enhanced and propelled by cross-references and new keywords. My latest ventures include the actual address of an event down to the floor and apartment number, and a separate field for 'Whose House' it is.

As much as I enjoy this process, it is very time consuming, and takes away from the time spent on the actual projects themselves. However, without it, random travel through 'memory lane', and consequently some of the concepts, may never come to light. It is also a process that is not possible to delegate as much of the information comes from memory. That is what differentiates this personal archive from most institutional archives, as it contains – for the most part – names and places that have no other reason to be recorded or remembered, no celebrity status, no great historical event, but that simply happened at the intersection of place and time where an eager photographer with a camera was present.

WR: Can you talk a bit about how music/sound (the hundreds of LPs/records you own) fit into your creative endeavour?

LS: Anyone who says 'I love music', and by doing so intends to sound like it is some sort of unique or special trait, is delusional. Music is universal, and almost everyone loves music. One of the shocking exceptions is one of a handful of artists I truly admire and respect, Federico Fellini, who claimed that he practically never listened to music. I used to listen to music almost incessantly but have curtailed this activity considerably in the last couple of years.

I could wax poetic about my relationship to music, but suffice to say that I started collecting records at the age of 15 and stopped acquiring physical music media in earnest around 2001, shortly after the demise of the original World Trade Center, where I used to DJ regularly on Wednesday nights for a period of four and a half years. By then, I would estimate my 'record' collection in both vinyl, cassette tape and CD formats numbered around 10,000 units. I was a radio DJ during my college years, and had experimental radio shows where I not only played alternative and experimental music, but also utilized the radio medium itself to create soundscapes and cacophonies to the dismay of some listeners and the delight of others.

One time I wired the two turntables to the different channels, left and right of the transmitter, and recruited another DJ friend to play his set on one turntable while I played my set on the other, resulting in the programs playing simultaneously, each from the different stereo speakers. Listeners were calling in to report the 'technical problem'. This was one of the actually less creative programs of many. Furthermore, the fact that our frequency was extremely close to that of a Christian station caused a lot of aggravation to listeners of the latter, who would on occasion get interference from ours. Somehow, I was very bold in my 'creative endeavours' during that period, but staying well within the law and the regulations of the Federal Communications Commission.

I regarded, as I still do, DJ sets to be temporal sculptures. I also saw them as journeys, not unlike a ride on a train where the landscape shifts gradually and within a period of an hour or so you might experience mountains and valleys, lakes and forests, bridges and monuments, cities and rural areas.

In some ways, the record collection was also instrumental in helping me develop a discipline in organizing and cataloguing series by genre and artist; a discipline which later became helpful in organizing the photographic archive.

WR: You've had at least three long term 'jobs': flight attendant; Kodak; and DJ. Can you talk a bit about how those 'jobs' shaped your practice?

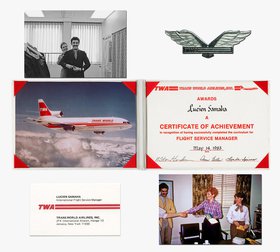

LS: I was born an airline brat. My father and four of his brothers at one time or another worked for various airlines. From a very early age I wanted to be a flight attendant. As I came close to the age of qualifying for the job, I had already fallen in love with photography, and I thought that the airline job afforded me great opportunities to expand my field of vision, so to speak, and indeed it did. Unfortunately, in the first couple of years, namely 1978 and 1979, I didn't photograph as much as I now wish I had. 35mm cameras were still bulky and heavy, and as a purser, I had to carry not one but two crew kits, one for my clothes and personal items, and the other for the airline and crew business. Believe it or not, in those days we had to hand carry our luggage as 'wheelies' were not yet invented, so the additional weight of a camera and flash unit were a deterrent.

In 1979, the Olympus XA was announced and I purchased one within a few months of its introduction. I had serendipitously gone to the then premium of camera dealers, Ken Hansen Photographic in NYC, and asked specifically for this type of camera. It was one of the first professional-quality compact cameras in a clamshell design; a rangefinder with manual functions including f/stop settings as well as manual focus. Weighing 7.8 ounces with batteries (221.15g) and measuring 2.567 by 4.123 by 1.572 inches, it was the ideal camera for the job. This camera, which I still have, as well as three more I purchased later on, dictated my style to this very day. I was enamoured with the portability and the ease of use of the snapshot camera and the resulting aesthetic, where one can take solid, well-composed photographs, as well as quick, fleeting images with a simple, sexy, single-handed maneuver of the clam shell and a click of the button. Being a manual focus camera, and with that extra focusing step often disregarded, I often had out-of-focus images that also became part of my aesthetic. Not so much as 'I love the out-of-focus image', but rather an acceptance that this also can be a result of the photographic process that can sometimes result in delightful surprises, not to mention motion blur, and of course 'wrong' exposure. It was also with this camera that I discovered a couple of signature techniques, 'dragging the shutter' with flash photography and of course the hand-held self-portrait, now expediently referred to in social media as the 'selfie'.

The flight attendant years not only allowed me to photograph on the streets of major European and Middle Eastern cities, but also exposed me to a world of photography different from the one in New York or the USA in general. European magazines dedicated to photography were vastly divergent from their US counterparts, which tended to emphasize technique over content. Of course, Life Magazine was known for its photography, but it was photography with news interests, whereas the French magazines Zoom and Photo and their Italian editions, as well as the international magazine Camera, offered an expansive view into the possibilities of creative photography. Furthermore, at that time it was nearly impossible to find high-quality, high-fashion, European magazines in New York, and I used to buy as many as I could afford and/or carry back from my European destinations. These magazines with the photography of Albert Watson and Patrick Demarchelier peaked my interest in fashion photography.

In 1984, I began developing a fashion portfolio with which I would attempt to seek work from the magazines, specifically the new breed of magazines dedicated to the younger set, such as Per Lui in the Italian Vogue family, and the alternative Max magazine, both out of Milan. In contravention to the slick standards of the day, I used my 'snapshot' aesthetic to make raw, grainy fashion photographs, which were less on product and more on emotional appeal. Not having assisted a professional fashion photographer, I had no guidance as to the inner-workings of the industry, and as such did not work in teams with stylists, make-up artists or hair stylists, but did everything myself in collaboration with the model, who often were just friends whom I dressed in my own clothes from Fiorucci and a wide selection of second-hand/vintage treasures. In 1985, I took a three-month leave from Trans World Airlines (TWA) and set up a short residency in Milan, the proving ground for young fashion photographers, where I boldly walked into magazine offices without appointment to show my book, and where I never passed the receptionists. Although, and I don't remember exactly how, I got the editor of the then cutting edge men's magazine Max to look at my portfolio as he was exiting the building one day, and he gave me an appointment to come and see him the following week. He was fascinated by my use of small cameras and the resulting photographs, and expressed interest in giving me an assignment. Alas, it was near the end of my leave from the airline and I didn't want to risk losing that job over a gamble. Furthermore, I realized by then that I wasn't really fond of the industry and that I had confronted my fashion demons with satisfaction and it was time to move on.

Had I known that my career as a flight attendant would come to an abrupt end less than a year later, I might have given the fashion photography gig a better chance, but as I already mentioned, I was pretty certain it wasn't for me. Plus, I always was aware that as soon as I would start doing photography as a 'job' I would most likely lose interest in pursuing it as a personal and life-long devotion. Within a couple of months of the beginning of the long strike by the flight attendant unions against TWA, I decided that it was time to abandon that ship and move on to a plan I had while still in high school, which was to attend the Rochester Institute of Technology to study photojournalism. I didn't like the program and I had a very difficult time getting along with the chair of the department at the time, so I switched to the Technical Photography department which was a more scientific based program about the nuts and bolts of photography, i.e. the physics, chemistry, optics, imaging sciences, as well as applications of the medium such as high speed, instrumentation, photomicrography, to name a few.

During this time, I still had access to the amazing facilities, equipment, and labs of the school, and I utilized them all fully to continue doing photography with even more experimentation through numerous self-assignments. Having had several years of travelling the world and partying in major cities, I was ready to dedicate myself to my studies, and I basically aced the first year. Coincidentally, at the beginning of my second year, Eastman Kodak's Professional Photography Division offered for the first time ever a full tuition scholarship to a 'photography' student, whereas in the past they had only offered scholarships to hardcore imaging science, chemistry, and physics students. I applied and received the scholarship, and became the first ever photographer to receive that honour. The only stipulation was a commitment to a one-summer residency at Kodak's Professional Photography Division, a prospect I was overjoyed to accept without yet knowing the specifics.

When the time came, I was assigned to the Worldwide Instructional Operations at Kodak's Marketing Education Centre, which was in plain sight of my student housing apartment with only a small corn field separating us. It was an architectural award-winning building for its design and functionality, stuck in the middle of nowhere in the town of Henrietta, NY. This department had the most jaw-dropping lab and studio facilities anywhere in the world, containing every possible dream machine a photographer could wish for; every possible film and print processing machine in the largest sizes available; massive enlargers on wheels with vacuum suction easels on the wall to hold large sheets of photographic paper; and, much to my delight, all the brand new digital technologies that were just emerging and were in initial testing phases, not to mention all the greatest cameras in all formats. I was assigned pretty much to all I was interested in, with the particular duty of testing the prototype of the first digital camera and to develop an instructional curriculum for its use and to eventually teach the technology and its applications to a dedicated team of sales personnel, as well as to targeted end users, which at the time were the major newspapers and news agencies.

At the end of my three-month residency, my supervisor asked me if I would consider part-time employment while I finished my last year at RIT. Despite a heavy academic load I accepted the offer, which eventually culminated in full-time employment upon my graduation. My first glorious assignment was to spend several months travelling with the prototype digital camera all over the world to introduce the new technology to potential buyers, mostly institutional, as in newspapers, magazines, police departments, and scientific research. During all this time, I continued photographing everything at every opportunity with an unlimited supply of film and processing courtesy of Kodak. My enlightened manager believed that the more we were able to use and understand the media we were trying to market, the more successful we would be in selling it. I would return from every trip with two or three large Ziploc bags of exposed films, in all varieties, and would spend the first three or four days feeding them to the processors while I filed my debriefing reports. I was like a kid in free toy land. It was simply incredible to be able to shoot so much without any worries or guilt over the costs of sensitized materials and their development, not to mention the ability to print and scan so much of it, at a time when most people didn't know what a film scanner was. Furthermore, through corporate deals, we had access to the best computers from Apple and nascent versions of Adobe Photoshop, not to mention an astounding variety of other software, imaging peripherals and printers.

This unfettered access certainly must have had an effect on my 'practice' and photographic style. I was perhaps intentionally lackadaisical in composition or technical attention due to the fact that I could simply shoot endlessly, knowing that some of the photos would come out great. Of course, the more unconventional the results, the more encouraged I became to be even more bold and experimental. For example, on a trip to Tokyo, I used exclusively a Contax T2 with flash for every single photograph, which in the end numbered in the several hundreds. I would first put a filter of a particular colour on the lens, and one of another, sometimes opposite colour on the flash, while shooting colour reversal film at triple the ISO, which I would then push-cross-process into colour negatives. Early technology scanners would not 'know' how to deal with the negatives, and the results were often quite beautifully unacceptable. However, later generation scanners would simply render the whole thing into conventional imagery.

During those years at Kodak in Rochester, I had limited my social life in order to stay hours into the night working in the facilities. But the time came when I was transferred to New York City to work in the Marketing and Sales office, as the philosophy of the company decreed that in order to move up in management, one had to have experience 'in the field', face-to-face with the customers. By this time I was very happy to return to my old stomping grounds, all expenses paid. I did indeed interface with some of the most important photographic powerhouses and individual photographers, and confirmed to myself that I had done the right thing by not pursuing a formal career in photography. Of course, the rewards of being published and recognized by one's peers and by the public at large are enormous. But looking at it from another angle, there was an editorial process that was not without its powers to limit creativity. What editors would consider 'publishable' photos were not necessarily the best or the most accurate to the real events. To this day I cherish the freedom to do whatever I want with a camera.

By 1995, I had had it with the corporate job and decided to try the freelance route. After a few failed attempts to enter the magazine world, particularly the travel and/or lifestyle magazines, I relied mostly on a meagre income from random and sporadic DJ gigs in the downtown Manhattan scene. During my years as a flight attendant, and later while travelling frequently on business for Kodak, I would seek out record shops wherever I went, and would purchase dozens of LPs, mostly from the 50s and 60s and primarily for their cover art, not to mention their $1 or less price tag. As I started listening to the music purely out of curiosity, I began to (re)discover an amazing genre often referred to as 'elevator music' by most. But the stuff was not all simply Muzak. There were some incredible compositions with ingenious orchestrations played by very talented musicians. Yes indeed there was also some kitsch factor, but I combined both the serious and the lighthearted in my sets in underground Lower Manhattan lounges and began to amass a cult following. As most of the early fans were actually friends, I would photograph them as I would at any other party we might attend.

The beginning of this phase started in around 1994, before I had left Eastman Kodak. I wore a suit by day, and by night vintage, kitsch clothing I had collected from Las Vegas, San Francisco and other large city thrift stores. I took up where I had left off in nightclub photography in the early and mid-1980s in New York's mega-clubs, but this time from the DJ booth, which was invariably among the revellers, as I insisted not to be put in a dark booth away from the crowd, but to be in the middle of the action. After a few months of small yet very successful gigs around town, I was approached to produce a night at the top of the World Trade Center in The Greatest Bar on Earth, a magnificent tourist-oriented venue, which found itself depressingly empty just as the last trains left for the far suburbs. It was my task to bring in some business, and the management there decided that the type of music I was playing and the crowds I was attracting were more suitable than a hard-core techno or hip-hop crowd. The first two to three weeks were frequented by my regular, well-dressed (it was the summer of the slip dress) and ready-to-party crowd, modest in numbers but high in the cool factor. The word got out, and by the third week the lines started forming at the ground-floor elevators waiting for the ride 107 floors into the sky. The inaugural party was in April of 1997, and the gig was supposed to be for only three months. It lasted four and a half years, until one week before the fateful September 11. Until the end, one night of Mondo 107, as my party was called, occupied the highest revenue point ever for that venue.

From the beginning until literally the beginning of the new millennium, I continued to photograph on film using a Contax T2, but in January of 2000 I purchased my first point-and-shoot digital camera after a hiatus from digital-capture for ten years. The difference between the images of one medium and the other is quite notable, not simply in the look, but also in the content and in the method. The switch to digital was significant in many ways. I became even more prolific, and this is where the archive itself became better-fed and more hungry at the same time. Concurrently, new generations of software were becoming available for improved database and keywording options, and for much larger archives. Photo Exif data changed my life.

To read part II of this interview between Lucien Samaha and Walid Raad, follow this link.

To explore an online archive Samaha produced especially for Ibraaz Platform 006, follow this link.

Lucien Samaha (b. 1958, Beirut) is a New York-based photographer whose work has been shown internationally, including in exhibitions at the Museum für Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt and at the Cooley Gallery, Reed College, Portland. He was a finalist for the 2004 Nam June Paik Award. After his time at TWA, Samaha worked for Eastman Kodak Company and then as a DJ on the 107th floor of the World Trade Center, continuing to document his hours at work and his personal life.