Essays

Works on Paper

Artists Intervening in Lebanese Dailies

Over the course of three months in 2016, between 30 April and 25 June, twelve artists – Ahmad Ghossein, Annabel Daou, Caline Aoun, Daniele Genadry, Gilbert Hage, Haig Aivazian, Ilaria Lupo, Nada Sehnaoui, Omar Fakhoury, Raafat Majzoub, Sirine Fattouh, and Walid Sadek – were commissioned by the Association for the Promotion and Exhibition of the Arts in Lebanon (APEAL) and Temporary Art Platform (T.A.P) to intervene in Lebanese newspapers for the project Works on Paper. Four major Lebanese dailies took part: As-Safir (Arabic), Al-Akhbar (Arabic), The Daily Star (English), and L'Orient-Le Jour (French). These four dailies remain some of the most widely read in Lebanon.

Curated by Amanda Abi Khalil, Works on Paper proposed to use the newspaper not only as a means for publication, but rather as a matter of a space for creative intervention. The curator extended the invitation to participate in the project directly to the general directors of each newspaper, and each of the dailies negotiated the terms of the project with the curator. Items discussed included the amount of space offered to the artists, the placement of the interventions, the location of the mediation box (which provided the artist bio and brief project description), and an agreement on the days the newspaper would publish the interventions, all in return for a nominal fee for the provided space. Eventually, the curator and artists were put in touch with one representative, an editor or journalist from each of the newspapers that became the liaison between the newspaper and the project participants. After the curator and each newspaper developed an agreement, Abi Khalil then distributed artist interventions among the newspapers based on the amount of space needed for their work, while providing an array of stylistic and content choices in each month's edition.

Interventions were published on the last Saturday of April, May, and June 2016 in each of the four newspapers. Content varied widely, including an open-call for fortune telling by Annabel Daou in The Daily Star, to a fictional interview on the creation of a new Lebanese capital by Ilaria Lupo in L'Orient-Le Jour. Some artists worked directly over the form and content of the newspapers by intervening over content and text, while other artworks appeared as an advertisement or an image accompanying the newspaper headline. Some interventions seamlessly fit into the form of the newspapers, while others left some readers confused, misinformed, and infuriated. If any site-specificity occurred in the artist's interventions, therefore, these choices manifested after the newspaper assignment was given to the participants.

The collaboration brought two very different – yet resonant – worlds together. On the one side, editors and managerial staff who were usually focused on keeping their respective newspapers afloat also grappled with the challenges of hosting artistic interventions. Suddenly, they found themselves working on longer term projects with artists that differed in form and content from the material and nature of their habitual publishing. On the other side, artistshad to deal with the constraints or viewership of the print media environment in Lebanon.

Indeed, as media consumers opt for instantaneous resources like Twitter, Periscope, and Facebook over traditional newspapers, an added layer of difficulty has hit Lebanese outlets. Most Lebanese media is dependent on funding from political figures, parties, or regional actors, therefore making them vulnerable to political stalemates. With Lebanon's parliament, cabinet, and most political parties in deadlock, newspapers in Lebanon are stagnating, with few local political realities to write about. In a recently published article surrounding the issue of the declining Lebanese press, Georges Sadaka, Dean of the Journalism at the Lebanese University said, 'The Lebanese media has lost its impact and its authority, and that means a commensurate decrease in interest from the Arab regimes that were funding them.' [1]

In this context, Works on Paper created opportunities for relationship building, barrier breaking, and revitalized dialogue. Usually reserved for heated political debate, analysis on world events, and the occasional musings on international conspiracies, the pages of traditional media in Lebanon have rarely been offered to artists to produce site-specific interventions.[2] Likewise, while readers of traditional media in Lebanon often take part in debates on current affairs, they do not regularly engage with contemporary arts. Works on Paper therefore produced an opportunity for artists to critically engage with relevant sociopolitical themes, like Lebanon's waste management crisis, regional urban development, the role of the press, the use of public spaces, and more, while also connecting with an audience that does not traditionally engage with the discourses of contemporary art.

Most striking, however, was the fact that in Lebanon's politically-charged media scene, Works on Paper also allowed for one of the few moments that four major newspapers – with rivaling political views – all sat together in a room to discuss, of all things, art, in a time of worldwide crisis for print media. During this meeting, they came to a consensus on the title of the project and its manifestations – the outline of which forms the subject of this essay, which will consider each newspaper as an individual exhibition space within a larger curatorial project that explores the current state of things in Lebanon through the encounter of two civil perspectives: art and the news media.

The Daily Star

Founded in June 1952, The Daily Star was the leading English language newspaper in the Middle East throughout the 1960s, catering to the expats working in the oil industry.[3] When acquired by new investors in 2010, the paper developed a digital presence to become a source of Lebanese and regional news. Today, the newspaper continues to develop its online presence.

To note, in Lebanon, viewership and readership counts are closely guarded, because of their direct impact on advertising. Newspapers usually inflate readership counts to advertisers in order to retain their business. It is actually not clear how many papers are sold per day. In Lebanon, an external enforcement to share counts doesn't exist, neither is there a culture among papers to release them. With that said, the readily available data for The Daily Star is as follows: in 2009 their website registered more than 80,000 unique visitors per day. The 2011 circulation of the English language paper was 29,940 copies.[4]

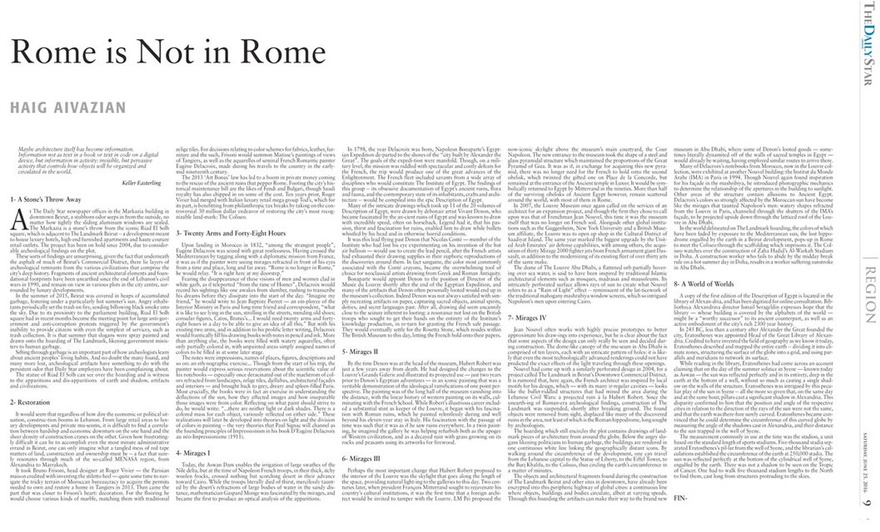

In the Daily Star, Annabel Daou, and Haig Aivazian restructured existing ongoing projects to suit the printed form of the newspaper. Omar Fakhoury's intervention altered the table of contents on the front page of the printed paper. The interventions do not appear online.

In April, Omar Fakhoury intervened in the Daily Star's puffs – the headlines on the top of the front page. The headline reads, 'Beirut erects a Monument paying Homage to Marika Spiridon', and is accompanied by a photo of Spiridon, a Lebanese legend from the 1950s who used to run a whorehouse in Moutanabi Street, Beirut. The puff refers the reader to page 9, which is in fact missing in this edition, causing the reader to look vainly for an article about a highly-contested space in Beirut that doesn't exist. (Many readers apparently contacted the newspaper directly, asking why a page went missing.)

Fortune by Annabel Daou is a series of palm readings with the image of the participants' hands pictured below a written interpretation of the fortunes. A month before the intervention went to print in May, Daou released an open-call in the newspaper asking for photo submissions of the applicants' palms. She hoped to engage with readers she would not usually reach, as she has performed this intervention previously at art spaces. Taking up a double page spread, twelve submissions were accepted from the open-call. The anonymous palm readings are structured around two questions: 'Where are you coming from?' and 'Where are you going to?' The project challenges notions of trust, intimacy, and the artist's public reception, as someone who uses intuition to translate the moment and then relay it back to the public in the newspaper – considered as a legitimate source for information.

In Haig Aivazian's text and image intervention, the series Rome is Not in Rome, he first describes a construction site on hold since 2004 near the Riad El Solh square and the Daily Star's newspaper offices in Al Markazia. Published in June, the selection is part of Aivazian's larger series Ivy Usurps the Place of Laurels, which investigates archeology and architecture as powerful tools that shape ideology and the constructed visions of the world, from the very first formulations of our global imaginary. The text in Rome is Not in Rome focuses on displacements of earth that occur in three kinds of constructions sites: sports stadia, luxury apartment buildings, and museums. The text is complemented by a digital collage of charcoal drawings of Coliseo, Rome; Burj Khalifa, Dubai; dome of the Louvre, Abu Dhabi; base of a Roman column, Beirut; concrete foundations of Guggenheim, Abu Dhabi. The image also considers the practice of drawing and its significance within a historical context.

As-Safir

As-Safir, one of the participating Arabic dailies in Works on Paper, struggled through the spring of 2016. Launched in 1974, the paper historically was one of the leading platforms for news for Arabic readers, and in some years, had leading Arabic readership counts in the region with a reported circulation of 50,000 copies in 2012, as reported by the Ministry of Information.[5]

About one month before the release of the first issue of Works on Paper, the president of As-Safir informed the curator that they would have to pull out of the project. Soon after, in April 2016, the daily announced for the first time that it would shut down all print operations, before finding an unnamed sponsor and downsizing the paper from 18 to 12 pages.[6] With the news that they would continue operations, they re-confirmed their participation in Works on Paper. A few months later, after 42 years in publication, As-Safir released its last issue on 30 December 2016.

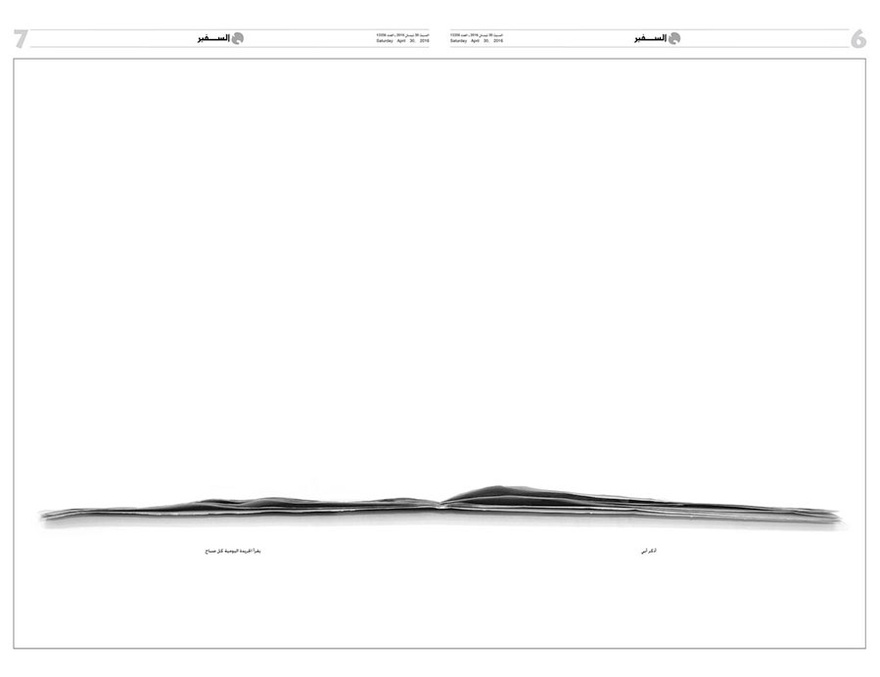

Walid Sadek (April), Daniele Genadry (May), and Ahmad Ghossein (June) published their interventions in As-Safir, with Sadek's and Ghossein's interventions visually mirroring the unraveling of the Lebanese print industry, as exemplified, too, in the demise of As-Safir.

Passive and poetic, Walid Sadek's intervention draws on the fading of print media while paying homage to his father, the famous political caricaturist Pierre Sadek (1938–2013). Sadek was recognized as a 'defender of press freedom.'[7] His editorial drawings appeared in print and televisual media for over five decades, and offered a rich commentary on local, regional and international socio-political history. In reflection of this passing age, Walid Sadek thus presents an image of the cross-section of an open newspaper, with a sentence in Arabic below the image translating to: 'I recall my father reading the daily newspaper every morning.' Sadek reflects on the past generation's relationship with the daily newspaper and its eroding presence in the public by addressing his father, a pioneering contributor to the dailies, who has since become a historical figure. By presenting such nostalgic words on the image of an open newspaper framed by the real thing, Sadek creates a multi-layered encounter between temporalities and conditions, from the past and present, to the soon to be memorialized.

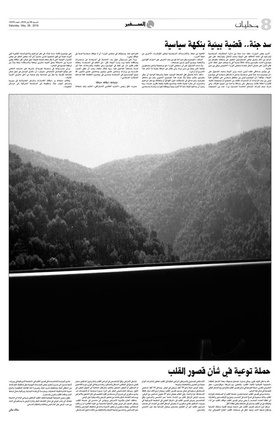

Connecting to such fluid juxtapositions, or over-lapping, was Daniele Genadry's intervention A missing view and The Slow Fade. On a double spread, black and white photographs of a landscape sit side by side, as four news headlines and a portion of each story's content surround the images. One of the headlines coincidentally relates to the environment, as it reads 'Jannah Dam..an environmental cause with a political flavour', which corresponds to the landscape images. In a similar move, then, the real becomes framed by the representation – here, the images that seem to accompany an actual news story have been presented as art, thus turning the present into an icon of sorts. At the same time, the work questions the capacity of the image to translate the present, or reality, in its inability to capture true time: that is, the impossibility of recording movement. Seemingly identical, Genadry uses the photographs to challenge the status of the image, as the two photos look the same, but they are different, thus charting a movement that took place when the shots were taken, but the image does not represent.

This question of representation was brought out of the realm of abstraction and into the material world of bodies and movements in the final project published with As-Safir. For this, Ahmad Ghossein printed the newspaper's slogan in Arabic on a full spread, which translates to: 'the voice of the voiceless'. The slogan is presented as a visual illusion, printed on grayscale that requires the viewer to move the paper back and forth so that the script becomes visible. Here, the disappearing slogan of the pioneering newspaper alludes to the crippling realities faced by print media, particularly As-Safir, and the subsequent impact these difficulties have had and are having on the media's capacity to be the voice of voiceless. Here, then, representation is grounded in the very form of the newspaper itself – a delusion to the eye.

L'Orient-Le Jour

Founded in 1971 after the merger of two French language Lebanese dailies, L'Orient-Le Jour is the only extant Francophone newspaper in Lebanon. Today, the paper continues to stand as the go to French language newspaper, catering to a liberal francophone elite of Lebanon.

Both Sirine Fattouh (April) and Ilaria Lupo (June) fabricated fictional interventions, each drawn from previously published texts, to call attention to the reader about the status of the city due its vulnerable past and its speculative future. Site-specificity occurred in both the interventions of Fattouh and Caline Aoun (May), who used the newspaper's archive to compose their project. All of the interventions were published in the culture section of the newspaper, page 15. A few days following each intervention, L'Orient-Le Jour published an article in the same location as the artists' works, summarizing the intervention for readers.

Sirine Fattouh's intervention Avis, published on 30 April, comprised of a series of fake cancellations of cultural and artistic events taking place on the day of publication 'due to circumstances', such as the closing of the Sursock Museum, Beirut Art Center, Ashkal Alwan, Metro el Madina, Galerie Tanit, Marfa, and Sfeir-Semler. Inspired by her research on the archive of L'Orient-Le Jour, the artist used the same opening phrases to introduce the cancellations, such as 'En raison des événments' (due to the events) or 'En raison des circonstances' (due to the circumstances). These statements appeared heavily in the newspaper during April 1975, the beginning of the Lebanese Civil War, when the cancellation announcements of public events appeared regularly without explanation. As part of her intervention, Fattouh published these cancellations in the newspaper's culture section above the agenda. Each cancellation was written in a box and the series of notices aligned towards the right edge of the page. Online, the intervention took on a video format that floated over the notifications as structured in the printed paper. Fattouh blurred the temporal and political realities for the readers, by cancelling performances, venue openings, yoga classes, and events at museums and art centres – thus intervening in readers' daily lives through their daily newspaper.

A few of the listed spaces responded when they received digital alerts that events at their own spaces were being cancelled and reacted critically to Fattouh's intervention. In the same location of the culture section, the paper published a statement about the project on 4 May. In this text, the project was explained, and Janine Rubeiz and Alice Mogabgab from Galerie Tanit, an art gallery in a Beirut neighborhood, published a response to the project below the text, in which they wrote: 'One cannot invoke conceptual art to manipulate public opinion in relation to an otherwise fragile situation. One cannot rely on conceptual art to demolish all of a sudden activity and the impetus of a whole cultural community mobilized around these events.' This response raises questions about the necessity to use art as a political tool of intervention to strike cultural memory in a country where the public already acknowledges the regularity and plausibility of the cancellation of events due to conflict. Nevertheless, Fattouh's disruption acted as a reminder both to readers and event organizers of their own vulnerability to the ongoing crisis in the region, especially in relation to the ongoing neighbouring war in Syria, which continues to economically and socially impact Lebanon today.

Published in May, Caline Aoun's intervention Au Lendemain played with the material status of the image using a digitization process that Aoun uses often in her practice, in which she repeatedly processes images through scanning and printing them from a printer almost empty of ink – until the original image becomes augmented, abstracted, and dematerialized. Aoun does the same to a small clipped image from a past printed issue of L'Orient-Le Jour, estranging it from its original context. The image underwent the scan and print process until it reached a larger size, and created a new meaning for the image. At the bottom intervention, the image retained the word "Au Lendemain", referencing the cycle of a day that rhythms the life of a newspaper, as it also suggests the notion of renewal or rebirth. The abstracted, pixelated lavender image takes up a quarter page of the culture section. This exhausted image plays on the saturation of images in the media, where the meaning of images tie to their materiality.

Ilaria Lupo's intervention Down the line, published in the June edition, builds on a satirical article published last spring by Executive Magazine on a new capital for Lebanon. Lupo's work is an interview with three experts – a Middle East market's advisor, an urban planner and archaeologist, and an economic policy researcher on this new global city to come. Maneuvering the stunt, Lupo begins the interview by begging the question – 'What are the reasons for creating a new Lebanese capital?' The interview is accompanied by a digital rendering of the capital, which includes a spaceport, giant wind turbines, and a waste treatment facility.

Al-Akhbar

Al-Akhbar produced its first issue in 2006, providing a new platform for journalists from other established firms to write for a paper that could 'address topics and issues that were previously forbidden'.[8] However, as most newspapers in Lebanon, they produce specific political views to a dedicated readership. Today, Al-Akhbar is solely an Arabic language printed and online newspaper, but from 2011 to 2015 they had a strong English web-specific platform that is now available only for archival purposes. Without a printed edition of the English platform, the online version became unsustainable, due to a lack of funds and advertising opportunities. In 2012, Al-Akhbar's chairman Ibrahim Al Amine reported the daily distribution at 15,500 copies, with an average of 5,500 copies sold per day.[9]

Raafat Majzoub (April) and Nada Sehnaoui (June) both used the surface of the newspaper as their medium, masking over and altering the news content within the spreads, asking readers to acknowledge the potentiality of the content and the medium itself. Gilbert Hage (May) also dealt with this idea of covering, as he referenced a historically censored painting in his photographic intervention.

In the April edition, Raafat Majzoub used both the print and online edition of the newspaper to share his project Knowing Bodies. The print intervention overlays two cut-and-fold designs directly printed over the spread's content, but leaving it legible. A quick response (QR) code in the lower corner of the page redirects the reader to two videos initially shared on Al-Akhbar's Arabic platform and now on the artist's website. Each video provides instructions and demonstrations from the artist, who shows the viewer how to manipulate each of the overlay cut and fold outlines – a square and cone container. In the videos, hands fill each container with different candy. In this, Majzoub alters the future of newsprint not as something that is dying, but as something that will continue to perform a function, as he directs readers to use their bodies, specifically their hands to upcycle the material and repurpose its use.

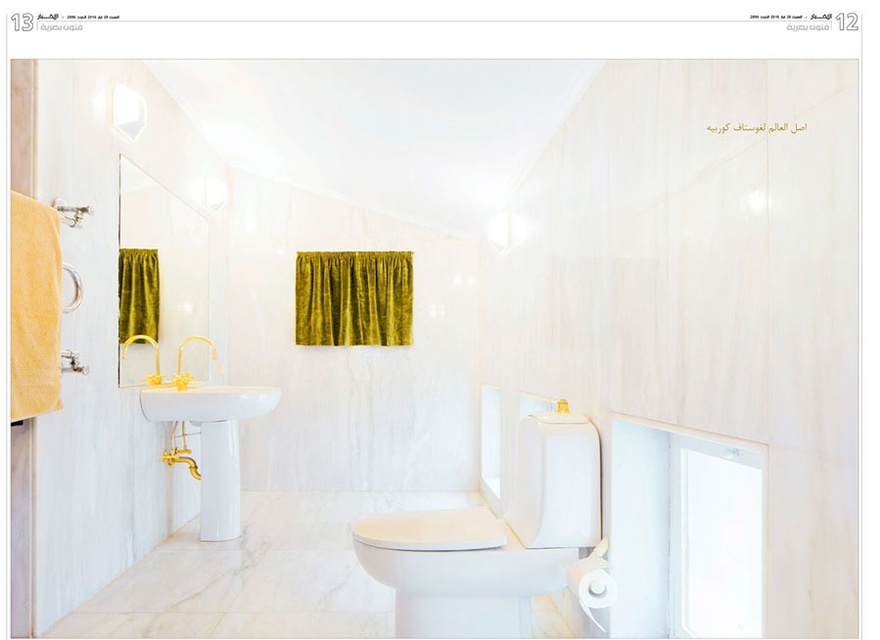

In May, photographer Gilbert Hage intervened with a staged photograph titled The Origin of the World. The photograph of a white restroom with gold adorned fixtures and dark green velvet curtain alludes to the censored 1866 painting by Gustave Courbet, L'Origine du monde, whichdepicts the torso of a naked woman lying on her back with her legs spread open and genital bare for all to see. The painting was apparently commissioned by Turkish-Egyptian diplomat Khalil-Bey (1831–1879): 'a flamboyant figure in Paris Society in the 1860s' who amassed a collection celebrating the female body until he fell into gambling-incurred debt.[10] Khalil-Bey installed the painting behind a green curtain in his bathroom, as referenced in Hage's photograph. Not much is known of what happened to the painting after this, except that its last owner was psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, who covered it with another painting. In fact, before the work was presented as a new addition to Musée d'Orsay collection in 1995, it had created no previous scandals. Since then, the painting has attracted artist interventions, including Deborah de Robertis's impulsive performance Mirror of Origin (2014)where she sat under the painting and revealed what we do not see in the image, exposing the inside of her vagina.[11] In the top-right handed corner of Hage's photograph the title of Courbet's work is printed in Arabic. Hage's work touches on notions of self-censorship, allowing the reader to consider how the image resonates in the medium it appears within - Lebanese print media today. Censorship maintains a necessary balance between prohibition and transgression, erotic pulses and social control.

For the June edition in Al-Akhbar, Nada Sehnaoui drew from her past newspaper interventions that formed her iconic series Painting L'Orient le Jour (1999), for which Sehnaoui spent the year 1999 manipulating the front page of L'Orient-Le Jour with paint and drawings, once a month. The series drew on themes of collective memory in relation to post-war Lebanon, by using the front page of the paper as a surface to silence, rewrite, and reinterpret the documented history of these events.

Sehnaoui's recent intervention for Works on Paper, Kellon, which means 'all of them',drowns the last page of Al-Akhbar in red paint, silencing the narrative that could have been printed on that surface. The only identifiable word on the spread is 'kellon', which is repeated between the lines and refers to the popular 2015 summer protests against the waste management crisis in Lebanon. At the time, protesters chanted 'Kellon' to denounce the whole political elite, rather than point fingers at specific party or politician. 'All of them' - the only response appropriate for a country in political deadlock.

Reflections

For the avid art viewer, these interventions are not a traditional encounter with the daily newspaper or contemporary art, but they have been subversively used for decades. Walid Raad's clipping of images and quotes from newspapers seen in multiple worksandRirkrit Tiravanija's untitled collages on newspaper transform the media into a digestible artwork ready to be displayed in a gallery, museum, or other art space. One particularly disruptive piece was Emily Jacir's SEXY SEMITE (2000–02), a series ofpersonal ads submitted by 60 Palestinian men and women and printed in the Village Voice, a New York city paper. The personal ads sought Jewish partners in order to make use of Israel's 1950 'Law of Return', making sly references to displacement or trauma. Performed three times, the press caught on to the artist's 'plotting' during the last intervention in 2002, post-9/11. The personal ads were eventually exhibited as documentation. Other initiatives have also used the newspaper and other print media to present contemporary art outside traditional spaces. Museum in Progress, founded in Vienna in 1990, held the exhibition Message as Medium, where at the culmination of the exhibition the interventions were packaged as a set and shared with the art world.[12]

At times, perhaps alongside a sense of urgency to act against the conventional mode of art and cultural production, contemporary art filters into the public realm in hopes of challenging typical styles of participation in the arts – either manifesting in a very directed and apparent way, at other times infiltrating daily life, and becoming apparent only to the conscious observer. Perhaps Works on Paper may seem like an idiosyncratic display of printed artworks, drawing on a range of themes, using various forms – from visual poetics to the repurposing the materiality of the paper, and requiring different levels of engagement from the reader. A simple examination of the project lends a reading of the curatorial and artist negotiations with the newspaper, a fading public platform that employs contemporary art and the subversive interventions to reinvigorate the public to digest the paper using content other than the daily news.

The interventions, in some ways, framed a narrative of each newspaper. Each newspaper approached the project differently on their online and printed platforms. The Daily Star, the oldest of these papers, took on the project for its purpose of working with paper as it engaged with the printed medium only, and did not feature versions of the content online (which remains an ambitious project for the newspaper staff). As-Safir managed to include the interventions, which can be seen as visual artifacts of the demise of the printed paper itself. L'Orient-Le Jour published articles on each project after the interventions occurred, further contextualizing the projects for their readers in the dedicated culture section. The interventions in Al-Akhbar all dealt with similar notions of masking, altering, and censorship alluding to the mission of the newspaper as stated by one of the cofounders to provide a new platform to discuss issues that were previously forbidden.

Together, the artworks featured in the Lebanese dailies inspire one to consider the context of Works on Paper, and how these interventions resonate within their respective papers, which each offer a perspective on the history of Lebanon and its civil society. Artists use the intervention to explore Lebanon's civil history, offering non-linear temporal views of the country and the capacity of the medium itself - from Sadek's and Ghossein's interventions that mirror the demise of printed expression and media, to the content that speculates the construction of collective perspectives by Lupo, Fattouh, Genadry, and Aivazian, to the elimination or masking of content by Sehnaoui, Hage, and Fakhoury, and to the consideration of notions of exhaustion of material and the role of the body during the process as seen in Aoun, Majzoub, and Daou.

[1] Rouba El Husseini, 'Once a beacon, Lebanese dailies lose regional sway', Middle East Eye, March 31, 2016, http://www.middleeasteye.net/news/once-beacon-lebanese-dailies-lose-regional-sway-19938460.

[2] Editor's note: There was a project called Kitab fi Jaridah (a book in a newspaper) that published Arabic literary texts and images of artworks in Arab newspapers including the Lebanese. This was a UNESCO project that started in 1995, relaunched in 2003: http://www.kitabfijarida.com/newspapers.html.

[3] 'The Daily Star – A Short History', The Daily Star, http://www.dailystar.com.lb/AboutUs.aspx.

[4] Paul Doyle, Lebanon (Bradt Travel Guides: 2012), p. 78.

[5] Jad Melki, Yasmine Dabbous, Khaled Nasser, and Sarah Mallat, 'Mapping Digital Media: Lebanon', Open Society Foundations, published online on 15 March 2012, p. 20. https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/sites/default/files/mapping-digital-media-lebanon-20120506.pdf.

[6] Rouba El Husseini, 'Once a beacon, Lebanese dailies lose regional sway', Middle East Eye, 31 March 2016. http://www.middleeasteye.net/news/once-beacon-lebanese-dailies-lose-regional-sway-19938460.

[7] Elie Hajj, 'Lebanon Loses Pierre Sadek, Prominent Political Cartoonist', Al-Monitor, 26 April 2013.

http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2013/04/lebanon-political-cartoonist-dies.html.

[8] Ibrahim Al Amine, Chairman of Al-Akhbar, in conversation, The Business Year, 2012,https://www.thebusinessyear.com/lebanon-2012/finger-on-the-pulse/interview.

[9] ibid.

[10] "L'Origine du monde [The Origin of the World]," Musée d'Orsay, http://www.musee-orsay.fr/index.php?id=851&L=1&tx_commentaire_pi1%5BshowUid%5D=125&no_cache=1.

[11] Benjamin Sutton, 'Artist Enacts Origin of the World at Musée d'Orsay-And, Yes, That Means What You Think', Artnet, June 5, 2014, https://news.artnet.com/exhibitions/artist-enacts-origin-of-the-world-at-musee-dorsay-and-yes-that-means-what-you-think-35011.