Interviews

In Lieu of Absence

Taysir Batniji in conversation with Silke Schmickl

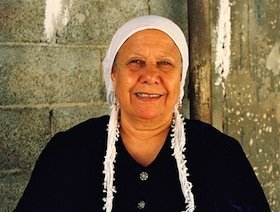

Palestinian artist Taysir Batniji's work spans video, painting, performance, drawing and installation. The artist, now based in Paris, has recently produced a new video alongside Paris-based film label Lowave. Independent curator and Lowave co-founder and director Silke Schmickl spoke with the artist in May about the new work, which premiered at the Cinéma du Réel festival at the Centre Pompidou this March within the programme Rising Images, curated by Lowave, and was selected for the Expérimental-Essai-Art-Vidéo competition of the festival Côté Court in Pantin. In this new piece, entitled Ma mère, David et moi (2012) Batniji makes use of recorded conversations with his mother in Palestine to weave together a narrative about separation, absence and the failures inherent in modern methods of communication.

Silke Schmickl: What is the background of this new video? How did you get the idea for this work?

Taysir Batniji: I got the idea for Ma mère, David et moi about two years ago. I have been settled permanently in Paris since 2006 and it was impossible for me to return to Palestine to see my family for many years. During this period, the only contact I had with my mother was via regular phone calls, during which we talked about daily topics, family news, souvenirs of her life, her marriage, the birth of my brother, her health, and so on. But sometimes those conversations also spontaneously opened out to encompass more general issues and in particular the current social and political situation in Palestine. Those conversations became a precious source of information for me and I decided to record them in order to document her situation over there and mine in Paris. The idea of the project was born out of and motivated by those dialogues that had become a substitute for the real, physical encounter. When I decided to make the video, I listened to the recordings again and initially wanted to use them in their entirety, including the intimate parts. I then realised that due to technical problems such as power cuts, intermissions and bad sound quality, the conversations were incomplete. So I decided to accentuate this aspect and to use it as a metaphor for the impossibility of being physically in the same place. I wanted to use only bits of our conversation that function rather as moments of disruption. The first scene starts with a beeping noise that resounds like a broken voice, the telephone line has problems connecting and it sounds like someone is choking.

SS: The video weaves together three layers of reality: the one of your family based in Palestine, your daily life in Paris and the mediums that seem to connect those two worlds but that are in fact rather a source of separation, misunderstanding and ideological propaganda. The combination of different realities is also visible in the different textures of the images, which creates a dense visual and sonorous network of associations. Where do the images and sounds come from and when and where were they recorded? How did you get the idea to connect those realities and how does your personal story relate to this?

TB: In all my videos there is this idea of a diary, a personal journal rather than the evocation of a particular situation. I make use of a personal archive, bits and pieces of documents that retrace my life in the last few years. And then there were these conversations with my mother, as well as media recordings, TV documents, visual and sound objects that I had kept. I tried to bring those disparate elements together and to reflect on the fragmented aspect of my life. The conversations connect those elements and function as a leitmotif together with other recurrent elements such as the rain, flies, planes or birds. The genesis of the video can be compared to the weaving of a tissue, or embroidery, developed around this improbable, impossible, personal conversation. In my context, it is difficult to separate the different elements: the public and the intimate, the private and collective intermix - I needed to deal with everything at the same time. The time period between 2000 and 2012 was characterised by important events such as the Iraq War and the Gaza War in 2008/2009. There was this general feeling of a blocked and suspended situation that I illustrate for example through the metaphor of a fly lying on its back, turning around on itself and being unable to fly. The images of the Iraq War constitute another important visual source for the video. The media treated this event in a very ambiguous way. And as if I wanted to protect myself from those influences and this type of information, I decided to film the news coverage with my own camera. I hadn't watched these images for a while but I knew that they were there and I had shot them with the idea to use them one day for an artwork. I did not want to locate them, even if some spectators might be able to identify them occasionally. But not everybody is able to connect them to the Iraq War. I wanted to treat the war in a more general sense, without a precise date or geography. I wanted to concentrate on the human aspect more than the political. In this video I express my own logic and association of the events, but the spectator might have other associations than the ones that I foreground.

SS: Ma mère, David et moi is composed of your videos, photographic images, TV recordings but also images from YouTube and Google. Was it the first time that you used such different resources and externally produced images? How did you proceed in your selection? Is it something you would like to explore in the future?

TB: It was the first time that I used images from Google and YouTube but not the first time that I used different image sources in a video. In Transit (2004) you find digital stills and video images, as well as analog photographs, and also in Gaza-journal intime #1 (2001) and #2 (2007). In Ma mère, David et moi, I also used an extract of my installation Sans titre (2002). In this photographic project, I already used images from the Internet, portraits of young Palestinian martyrs who were killed during the Second Intifada. I converted them into black and white, reframed them, and transformed the faces into glossy black stickers that I transferred on a mat black cardboard. The result was a glossy negative on a mat surface. I began developing this series in 1998, when I started working on the idea of disappearance. I present the portraits in one block, with each portrait next to the other. Depending on the position of the spectator and the light situation, the portraits are visible or not. In the video, a sequence stems from this installation and it is another example of me making use of existing images. It is an experience that interests me but it is a tool and not a principle, I only access it when there is a specific reason.

SS: The use of text is also a particularity of Ma mère, David et moi. To my knowledge, it's the first time that you use text as a visual element in a video. It creates a story line that holds the disparate images together and places you in the centre of the video. It was an element that came at the end of the production - can you tell us more about it?

TB: Initially, my idea was to structure the video through chapters but it was too illustrative and also a bit didactic when the titles appeared like an introduction to each sequence. So I took out my diary and selected extracts that I had written. I wanted to give a poetic dimension to the video. I chose very subjective sentences that were not expositional, sentences that expressed a sentiment, a sensation or a souvenir. Dissociated from their original context, they were fragments just like the images. They contribute to the plot without being historical or linear and rather punctuate the video. I decided to present the scrolling text on the bottom of the image to refer to news channels such as CNN or Al-Jazeera, where you can read all kinds of information and breaking news. It is kind of a parody. In my video the texts give some information without going deeper into the illustrated reality. I used them rather as a sensation, a souvenir, a dynamic element, a flux.

SS: Your body of work includes many different media, ranging from photography, drawings, performance and installation art to video. Video is maybe the media that you use least often, so how do you relate to this media? Is it something you would like to develop more in the future? In one of your most recent solo shows in Paris, at Eric Dupont gallery in December 2011, there was no video presented. Was it your choice or the choice of the gallery?

TB: In all of my works, the choice of the medium is motivated by the idea that I want to express. I mainly used video until 2007 because it was the medium that was the most adapted to my way of life. I was constantly moving at that time and had a very unstable and nomadic existence. The videos from that period reflect and document this situation. Since then I have settled down in Paris and started a family. And this new situation found an echo in my work. I now have a studio and concentrate more on installations, drawings and photography. But this doesn't mean that I don't want to work with video any more. I think in the future I would like to work more with fiction and videos that I could produce in a more professional environment, with actors, scenography, and using more sophisticated technical equipment as well. I am currently less interested in documenting my life and I feel that somehow Ma mère, David et moi closes a chapter and that I am entering a new phase of reflection. Regarding the exhibition at Eric Dupont gallery, it was my choice not to present video this time. There was no need to exhibit videos that have been shown many times before and I wanted to show new works, installations and texts, in situ. For me, an exhibition is not an archive or a retrospective but rather a new elaboration, an announcement of projects to come or works in progress. It is an occasion to show the most recent productions and take the risk of showing unfinished or recently begun projects.

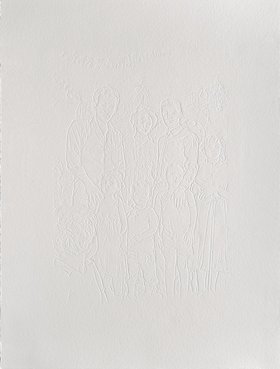

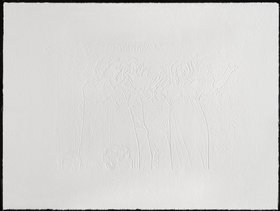

SS: You recently completed a very important series of drawings entitled To my brother (2012) within the framework of the Abraaj Capital Art Prize, which you were awarded together with Raed Yassin, Wael Shawky, Risham Syed and Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige. It is a very personal work, dedicated to your brother and is another piece that refers directly to your family and a personal story. Could you say something about this project?

TB: My work is always directly linked to my life. Many consider my work to be exclusively political but if you look closely, you can see that even if there is a political dimension my creations are always first and foremost based on a personal experience. As a Palestinian, this experience is constantly connected to current events and you cannot always separate it from the collective background. Transit, Gaza-journal intime, Ma mère, David et moi - all these works depict situations that I have experienced personally. The loss of my brother was a very painful experience that had a deep impact on my life. In 1985, we celebrated my brother's wedding with my family in Gaza. Two years later the First Intifada broke out and my brother was killed by an Israeli sniper. I was wondering how I could translate this experience and how a personal loss can be represented. How I could render something absent tangible, and materialise a memory. Two hours before my brother was killed in a demonstration, he had drawn an Israeli soldier shooting someone in my sketchbook. One of my other brothers or I erased the drawing but the traces remained visible on the paper. I kept this paper for a long time. A couple of years ago, I was leafing through my brother's wedding album and decided that I wanted to make something out of it, an homage to my brother. I scanned all the images and searched for a solution that would give them the same texture as the erased drawing. So I etched a series of 60 inkless 'drawings' on paper, based on the family photos from the album. These 'drawings' hark back to a happier time, one of joy and family gatherings. My brother was somebody who loved his life, who fought for liberty. The three-month-long realisation of the series took a performative character that can be compared to Hanoun (1972-2009), Voyage impossible (2002-2009) or Comme de l'eau (2008). As with all these works, To my brother requires an intimate relationship with the viewer and you have to stand close in order to discern and appreciate the fragile outlines of the drawings that are not or hardly visible from a distance. The series is supposed to stay together; it is a unique and irreproducible body of work that is part of the Abraaj Capital Art Prize collection.

SS: The subtlety with which you connect personal experiences by opening up to the political or social phenomena of our times is something that always strikes me about your work. It is for me a very efficient way to resist stereotyped discourses and the fashion for Arab art that has been growing over the last few years. Through this personal approach, you never succumb to producing work that 'satisfies' the demands of the market. Have you noticed a change in the way curators and collectors have approached your work against this background? How do you situate yourself in the contemporary art market and in regards to the Arab world?

TB: As discussed before, the personal experience is the engine of my work and it keeps me from bowing to stereotypes and helps evade trivialisation. Aesthetic and personal preoccupations are always more important than the political and I want to offer an alternative vision to the images we get from the media. I have always worked directly with curators, museums and institutions and this direct contact is a constitutive part of my work and reflections. My artworks have also often been shown in exhibitions that are not related to the Arab context.

Even if there is a growing interest in the Arab world, I have not changed my working method. Before there was less demand to show my work, but I keep on working in the same rhythm, with the same energy and the same convictions. I am conscious that this phenomenon can be ephemeral and it is very important for me to work independently from the demands of the market. The fact of being a Palestinian should not connect my work exclusively to Palestine. I hope that it goes beyond that and that it will not only be associated with the suffering of the Palestinian people and the political context. I want for my creations to establish a connection with art history, daily life, a certain intimacy. For me, the human dimension is more important than the political or geographical.

SS: You told me that you are working on a new work, preparing some exhibitions - what are your projects for the future?

TB: Right now, my main energy goes into the preparation of several upcoming exhibition such as When Attitudes Became Form Become Attitudes (CCA Wattis Institute, San Francisco), Tapis volants (Villa Medici, Rome), State of Transit (Open space, Vienna), Making History, in the framework of the project RAY (Museum für Moderne Kunst, Zollamt, Frankfurt). And I am working on a new installation with soap, L'homme ne vit pas seulement de pain, for the Marseille-Provence 2013, European capital of culture.

Born in Gaza in 1966, Taysir Batniji studied art at Al-Najah University in Nablus on the West Bank from 1985-92. In 1994 he was awarded a fellowship to study at the École des Beaux-Arts, Bourges, France, where in 1997 he graduated with a DNSEP (Higher National Diploma in Plastic Expression). Since then he has divided his time between France and Palestine, developing an interdisciplinary practice including drawing, painting, installation and performance, often closely related to his heritage. Since 2001, Batniji has focused on photography and video. He has participated in numerous international exhibitions in Europe and beyond. He has shown work at Untitled (12th Istanbul Biennial), The Future of a Promise, a collateral event of the 54th Venice Biennale, and Seeing is Believing, at the KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin. Previous exhibitions have included: This is Not Cinema!, Fresnoy, France (2002), Contemporary Arab Representations, the 50th Venice Biennale, Italy (2003), Transit, Witte de With, Rotterdam, The Netherlands (2004), The World is a safer place, Globe Gallery, Newcastle, UK (2005), Wanderland, Kunstmuseen, Krefeld, Germany (2006), Heterotopias, Thessaloniki Biennial, Greece and Sharjah Biennial, UAE (both 2007). During the 52nd Venice Biennale, Batniji was part of Palestine c/o Venice (2009) and the following year La Biennale Cuvee, Linz, Austria (2010). Taysir Batniji is represented by Galerie Sfeir-Semler, Hamburg and Beirut and Galerie Eric Dupont, Paris. He lives between Paris and Gaza.