Reviews

Al Araba Al Madfuna

Wael Shawky at the Fondazione Merz

Wael Shawky's films are almost never exhibited on their own. I saw films from his two most recent and most ambitious trilogies, Al Araba Al Madfuna (2012–2016) and Cabaret Crusades (2010–2015), on numerous occasions and at many different venues. Some form of installation practice always accompanies them. When shown at Documenta in 2012, the first two chapters of Cabaret were projected alongside a room-sized diorama of a medieval battlefield with fortresses, towns, and armies placed whimsically like characters from a children's pop-up book. At the 2015 Istanbul Biennial, the last film of the Cabaret trilogy, Secrets of Karbala, was exhibited in a centuries-old Turkish hamam, where Shawky made ample use of the structure's dank, cave-like interior to produce an ominous environment for his disturbingly violent restaging of the Crusades. The Al Araba Al Madfuna series began in 2012 at the KW Institute for Contemporary Art in Berlin, with similarly spectacular installation techniques. There, he buried the Institute's capacious ground floor gallery in sand so that viewers could be transported to the desert setting of the film's narrative. The dark room echoed the subterranean chamber in which Al Araba's child cast intoned the mythical history of an Upper Egyptian village.

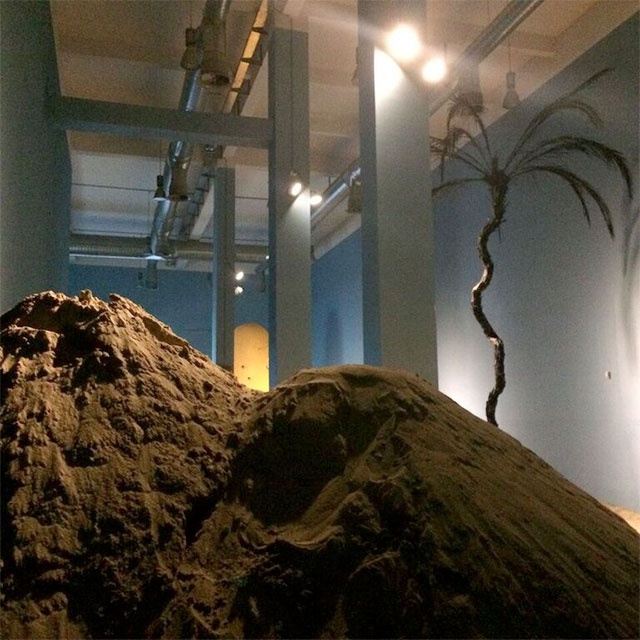

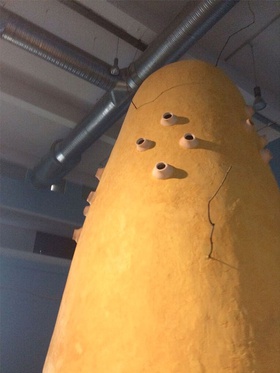

Shawky's current exhibition at the Fondazione Merz in Turin, which opened in November 2016 and runs to 5 February 2017, continues this tradition of site-specific installation. The show marks the first time all three Al Araba Al Madfuna films have been shown together. Like the KW Institute in 2012, the Fondazione was transformed by Shawky's installation practice from a featureless white gallery space to a dark desert cave, with the first floor of building completely covered in a deep sea of sand. The artist's fantastical interior desert appears with more drama this time around, with meters-high dunes reaching toward the gallery's high ceilings. A spindly black palm tree and a phallic, otherworldly silo burst through the depths of the sand, their precipitous forms vaulting upward as if in escape. The third film in the trilogy, Al Araba Madfuna III, immediately confronts the viewer upon entering the Fondazione's main exhibition space. Projected on a massive wall, the film inundates its audience with its representations of strange rituals and otherworldly landscapes. Al Araba Al Madfuna II is presented further in the main hall, beyond the crest of a large sand dune, while the first film of the trilogy is shown in space's basement floor, its underground placement mirroring the subterranean setting of the work. Shawky's robust command of spatial theatrics and portentous atmospherics echoes the haunted tone of the films themselves, which immerse the viewer in prophetic auguries, tales of cursed villages, and apocalyptic visions. Throughout his career, Shawky has displayed a sustained interest in the role of tradition and mythical narrative in the production of social identity. In the Al Araba films, the artist shows how these two forces can also work as slow poison, pulling a community toward social collapse.

The films are based on short stories written by Mohamed Mustagab, an Egyptian author who explored the contradictions of the Upper Egyptian village with wit, humour, and metaphorical flourish. Shawky adapts Mustagab's prose in a startling and sometimes deeply unsettling way: he employs large casts of child actors to recite the author's words while taking part in seemingly unrelated ritualistic actions. In the first film, a ring of boys, dressed in galabeyas and wearing fake moustaches, recite Mustagab's The J-B-Rs (translated into English in 2008 by Humphrey Davies), a tale of a small village that goes through disconcerting anatomical metamorphoses as it adopts a series of new livestock animals. While the children describe townspeople who begin to resemble their camels, another young boy digs a hole into the floor of their subterranean dwelling, eventually unearthing a mysterious, egg-like artifact. In the second film, a larger cast reads excerpts from two stories, Horsemen Adore Perfumes (2008) and The Offering (2008), as they explore the honeycomb-like ruins of an abandoned village. They speak of a malignant witch who seduced heroic adventurers, only to decapitate them and display their mutilated corpses to the horrified villagers in her thrall. As the children tell their tales, gesticulating solemnly to emphasize a particular point, the films shift to silent shots of the Nile and rural Upper Egypt, gliding amongst a bucolic stillness that contrasts wildly with the phantasmagorics of Mustagab's fiction.

The final film, based on the story Sunflowers (2008), is the most ambitious of the three, rivaling the baroque savagery of Shawky's more bombastic Cabaret works with its own form of quiet dread. Reversing the tonalities of the velvety black-and-white presentation found in the first two films, Al Araba III (2016) presents a lunar, misbegotten landscape through which Shawky's child cast wanders. This time set in Pharaonic ruins, the film exudes an almost extraterrestrial foreignness, as if the children are exploring the devastated remains of some long-lost alien civilization. Due to the tonal reversal, the night sky appears as a blinding white void, the stars as tiny motes of black. The young boys seem like revenant ghosts floating across the horizon, their torches glowing nebulae that seem to suck the light out from their surroundings. Once they descend into the cyclopean tomb, they are surrounded by fluorescent relief sculptures on all sides, their glowing bodies dwarfed by swarms of effervescing hieroglyphs and the rigid profiles of gods and kings that were carved into the walls millennia ago. Some of the children cook. Others make pottery. At times they meander through the swampy banks of the Nile or the rocky escarpment of the surrounding valley. During these moments, they look as if they have just wandered into the ebb and flow of an abstract painting, their small frames eaten up by a strange nature. They eventually find themselves at the bottom of a drowned pit that lays at the center of the ruin, a makeshift stairway leading into the incandescent purple murk.

As they explore this hallucinatory landscape, they tell their story. Like the other Mustagab tales that Shawky mines for the Al Araba project, Sunflowers (2008) tells a narrative of communal transformation and collapse that is brought about by the adoption of a new material tradition. The children tell of a village, now lost to time, that once took up sunflowers as an agricultural product. They devoted a small plot to the flower and eventually reaped the benefits by trading its seeds in faraway Cairo. The seeds could also be eaten by the townspeople without guilt – an extremely useful quality since drinking alcohol and smoking tobacco had been outlawed – but soon, the sunflowers begin to have a baleful effect on the town, strangling the other crops and eventually invading the village. What at first seemed a casual pastime and a source of wealth, soon reveals itself to be a calamitous, apocalyptic force, tearing the village apart and leaving nothing but half-forgotten tales in its wake.

Shawky presents a dystopian world in his Al Araba films in which tradition has gone sour. Shared ritual provides the basis for communal experience while also undermining that very togetherness, eventually resulting in suffocating oppression and collective eradication. That these films were made during the immediate historical aftermath of the Egyptian Arab Spring, which saw the nation's army play on various traditions of nationalism to create an even more draconian form of domination than that suffered under Mubarak, should perhaps come as no surprise. They represent communities in crisis, somnambulates moving through blasted lands, sapped of their strength by long-dead yet powerfully held traditions. We, as viewers, are also dragged into this nightmare by Shawky's deft use of installation techniques, an effect that is as disquieting as the implications of the films themselves.

Wael Shawky, Al Araba Al Madfuna, runs at Fondazione Merz, Turin, Italy, from 02 November 2016–05 February 2017. For more information, see: http://www.fondazionemerz.org/en/exhibitions/wael-shawky/