Reviews

Curating Conflict in Art

An I for an Eye and Death of a Cameraman

Jacques Rancière argues: Signification as conveyed in art is produced by its surroundings.[1] There is no formula to impose one meaning over another as time, language, social issues, and subjective experiences are some of several factors that constantly reshape meaning.

Political signification in artworks or curatorial projects, that are both motivated by particular social issues, is linked to the socio-political situation and the larger surrounding environment. This context is useful to consider the exhibition An I For An Eye,[2] curated by Stamatina Gregory and Andreas Stadler at the Austrian Cultural Forum, and Death of a Cameraman,[3] curated by Martin Waldmeier at Apexart, both in New York.

An I For An Eye attempts to exhibit destabilizing and challenging representations of global politics and conflict.[4] As the curators explain in their statement, the exhibition is an outcome of, 'this moment of seemingly permanent global warfare.'[5] The selected artworks represent varying conflicts through what the curators call 'counter-representations' to the images encountered in the media and visual culture at large. These artists provided an other image to these representations of disparate battles worldwide.

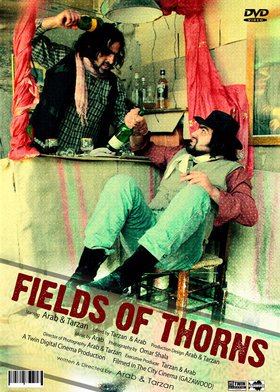

The exhibition presents the works of sixteen artists, which includes Tarzan & Arab's Fields of Thorns (2010), a film poster from their series Gazawood (2010), as well as a trailer the twins produced titled, Colorful Journey (2010), filmed in the style of a dramatic Hollywood action film yet shot against the backdrop of Tarzan & Arab's hometown, Gaza. Another Gaza inspired video, Gaza Zoo (Bath Time) (2010), by Sharif Waked, showed a donkey painted with stripes made to impersonate a zebra. In this piece, the 'zebra' is hosed down, its painted stripes slowly washing away, eventually exposing the donkey underneath. Waked's work was inspired by the events of late 2009, when an inventive zoo-owner painted donkeys as zebras to draw back the crowds after most of the zoo's animals were killed by Israel's air strikes.[6] In another artwork, Larissa Sansour's Nation Estate – Jerusalem Floor (2012) shows the artist gazing out from an open elevator door to the Dome of the Rock situated on the fourth floor of a futuristic high-rise tower, Nation Estate, while a projection of Shooting Images (2012) by Rabih Mroué deconstructs the nature of 'shooting' when the camera-lens and the sniper's gaze are trained at each other.

The second exhibition, Death of a Cameraman, also deals with conflict. However, in this exhibition it is conceived and organized around the footage shot from a mobile phone by a man in Homs, Syria in 2011. The actual video is viewable on a mobile phone at the entrance of the gallery. Shot-counter-shot takes place as the lens of the mobile phone encounters a sniper on the balcony of an adjacent building. Both 'shooters' face each other, a shot is fired, and the mobile phone falls to the ground.

The exhibition highlights the stakes of image making at moments of violence, with Waldmeier describing it as, 'An exhibition that acknowledges the presence of a new kind of image in which everything is at stake for the ones who make them.'[7] The artists featured include Rabih Mroué, also showing Shooting Images (2012) and Harun Farocki showing Eye/Machine I (2001), which shows the technological advancements of wreaking havoc without physical military invasions, and instead, playing out the violence from miles away. Other works include Hrair Sarkissian's Execution Squares (2008), a series of photographs depicting sites of capital punishment in Syria, Rudolf Steiner's Pictures of me, shooting myself into a picture (1998), in which Steiner fires bullets into a black box camera that then proceeds to shoot back an image of him, and Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin's Afterlife (2009), which employs the publicized image of executed Kurdish prisoners in 1979 after the Iranian Revolution. Death of a Cameraman exposes the contradictions involved in this type of image making – even a documentary image cannot grasp the reality, and even its recognition cannot be materialized.

Both exhibitions show the works of artists committed to a distinct cause or particular set of questions whose chosen meanings were influenced by the debates of the day, as it was only earlier that month that the news broke out of the use of chemical weapons in Syria. On 18th September 2013, news in New York captivated audiences with the threat of an impending US military strike on Syria. That week, the UN searched for chemical weapons. Barack Obama sought approval from Congress to launch strikes. The 'to bomb or not to bomb' debate was on every radio and news channel. Infected with the news of Syria – the images, the threats of military strikes, the heightened feeling of uncertainty – I viewed the display of conflict framed by both exhibitions and their particular curatorial criteria and found that the criteria of each exhibition foreshadowed the events of the day (or week, or month).

From one exhibition to the next, I considered the significance of showing Rabih Mroué's Shooting Images at two different spaces concurrently, and what this now meant in real time. I thought about Rancière, who states:

It can be said that an artist is committed as a person, and possibly that he is committed by his writings, his paintings, his films, which contribute to a certain type of political struggle. An artist can be committed, but what does it mean to say that his art is committed? Commitment is not a category of art. This does not mean that art is apolitical. It means that aesthetics has its own politics, or its own meta-politics.[8]

Exhibitions have the potential to urge their own points of contention. Curators can use the space of an exhibition to adjust expectations, and challenge preconceived notions. However, how much control is available to the curator to inform and direct these judgments? Curators apply particular methodologies that reinstate their criteria. Discursive events and supplementary texts enforce these ideals. However, particular points of reference, which remain outside of this criteria, can and doplay a significant part in constructing political gestures and meanings as they relate to the sociopolitical moment.

In the case of the two curatorial projects in discussion here, the exhibited work implies a commitment to the sociopolitical events they refer to and point out. Yet, viewing these commitments alongside current events and the current order of things thus reshapes the meanings that can be produced. So much so, that when encountering the political conflict in art, it is difficult to avoid the political headlines of the day, given it is arguably these very headlines that fed into the conceptualization of these thematic groupings. And so, in the month of September, I walked from one exhibition to the other and back again, watching Rabih Mroué's Shooting Images as Syria continued to go up in flames.

[1] Jacques Rancière, 'Politicized Art' in The politics of aesthetics: the distribution of the sensible, Continuum, London, 2004, pp. 60-66. Rancière specifically states that, 'There are no criteria, there are formulas that are equally available whose meaning is often in fact decided upon by a state of conflict that is exterior to them.'

[2] An I For And Eye is on view at the Austrian Cultural Forum from 18th September, 2013 – 6th January, 2014

[3] Death of a Cameraman is on view at Apexart from 13th September – 26th October, 2013

[4] Press release, An I For And Eye, on view at the Austrian Cultural Forum from 18th September, 2013 -– 6th January, 2014, http://www.acfny.org/press-room/press-images-texts/an-i-for-an-eye/ [accessed 18th September 2013].

[5] Ibid.

[6] View the donkeys being given a makeover: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u6ka0gKZSHw

[7] Press release, Death of a Cameraman, on view at Apexart from 13th September – 26th October, 2013, http://apexart.org/exhibitions/waldmeier.php#_ftn2 [accesssed 13th September 2013].

[8] Jacques Rancière, 'Politicized Art' in The politics of aesthetics: the distribution of the sensible, Continuum, London, 2004, pp. 60-66.