Essays

Amman’s West Side Story

Is soft power helping or hindering the state of the arts in Jordan?

East and west Amman each seem to exist as parallel realities. It would be erroneous to claim that they are polar opposites embroiled in an artistic tug of war. Yet the balance of equilibrium appears to be geared towards the west of Amman in terms of wealth, social status, foreign investment and public relations. This begs the question: does the dichotomy between east and west Amman impact on the state of the arts? Does soft power[1] exacerbate or help to alleviate those artistic differences? Can cultural diplomacy[2] initiatives help bridge the cultural divide within the nation's capital city? Then there is the issue of western involvement. The British Council and EU currently have a strong presence in the region; what impacts are these western cultural broker agencies having on local independent artists?

This critique of the art scene in Amman is based on recorded observations during a research visit to Jordan conducted in October 2012 by a cohort of Clore Fellows[3]. This view into the local arts sector revealed a burgeoning grassroots arts movement transcending the political vulnerabilities of the region, something this open-ended enquiry seeks to unravel.

'Welcome to Jordan!'[4]

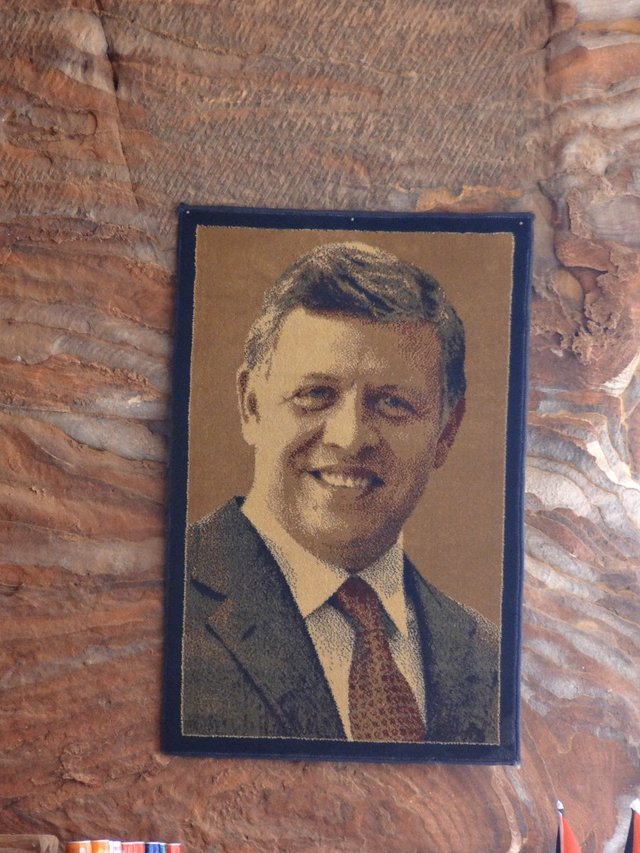

Bureaucratic constructions of visual culture are a strange phenomenon. Such constructions often tend to be an obsession with Arab heads of state, given visual omnipresence is a ubiquitous cultural marker. Glossy framed photographs of King Abdullah II are usual features of every lobby, but occasionally one stumbles upon more imaginative mediums of homage to the reining monarchy, such as tiled mosaics, carvings or textile portraits in far-flung locations.

Although King Abdullah II wields ultimate power, his authority over the arts is delegated to the Ministry of Culture. Yet, there have been over six different Culture Minsters appointed by royal decree in the space of the last three years, leaving Jordan's cultural sector crying out for a capable Culture Minister with the durability to build and sustain relations and foster long-term strategic changes in the arts. Upon meeting Salah Jarrar, the presiding Culture Minister at the time[5], we hear of his aspirations to transform the dominant mindset that regards art as a luxury and instil culture as a priority for all sections of society so larger audiences will attend cultural events.

Of course, there are some national cultural entities, such as the Royal Film Commission,[6] which are overseen by members of the Jordanian royal family who fulfil a public advocacy role in their missions. The Royal Film Commission is aiming to influence pop culture through fostering an appreciation of film that will lead to greater demand and eventually more investment in the sector. 'We'll know we have been successful when we stop existing and the industry can run by itself,' explains George David, current Director of the Royal Film Commission. David concedes a need to exercise reasonable sensitivity in order to win people over even though a passion for freedom of speech is at their core. There are no qualms in self-censoring content if necessary when rolling outreach programmes to more rural areas in Jordon beyond west Amman.

Amongst the broad array of past films screened[7] at the Royal Film Commission includes a documentary highlighting the capital's social divide called 'Amman: East vs. West'[8] made by film-maker Dalia Koury who sought to produce a visual commentary on the emergence of a "classist society" in the Kingdom. Here we come to the crux of the matter; Amman is a city divided[9] – there are in fact 'two Ammans'. The west side has the main substrate needed for cultural modernization; a cultural elite porous to liberal western influences, upmarket leafy residential areas, trendy cafes and art galleries. East Amman is in contrast more densely populated for its larger geographical area, generally less affluent and more conservative in outlook.

News features addressing art trends in the Middle East are few and far between but when they do emerge tend to be conflated with pan-Arab issues rather than contextualized with local issues of concern. Whilst much news analysis and public discussion[10] dwell on the ideological distinctions between the Middle East and NATO members there is far less emphasis put on explaining the intertwining complexities of different socio-cultural standpoints that exist within each Arab state and even less so the predicaments of individual cities within a specific Arab country. This is very much the case for Jordon. Whilst an East /West divide persists on a macro global level, a similar disparity is physically occurring at the micro local level within the east and west sides of city of Amman in terms of its morphological, topological, economic, social and cultural profile.

Ongoing 'westernization' of west Amman is exacerbating divisions in the city and by default has obvious repercussions to its evolving art scene. Dramatist Kamel Nuseirat's satirical play 'Neither East nor West' [11] attempted to tackle on stage "the social, political and identity dilemma that has faced the kingdom for decades".

Meanwhile, one of the many conundrums facing Jordan's government is the perceived lack of public support for the arts. The government is keen in principle to fund more visual art projects but at the same time is cautious since this may not gain popular support given the perceived threat that traditional values might be sidelined in the support of contemporary art forms. Politically speaking, it has been safer to keep the genie in the bottle to maintain the livelihood of the cultural scene. Weekly Arab Spring-inspired demonstrations demanding reform of autocratic rule and an end to corruption threaten the stability of the existing government.

In addition, local media criticize the use of public funds to produce contemporary performance deemed as elitist. Hence new forms of funded organizations have had to emerge. The Friends of Jordan Festival[12] is a relatively new non-profit organization run by a group of leading men and women from the private sector that operates through securing funding from businesses. Director Souha Bawab divulges that past audience demographics show lack of representation from lower socio-economic groups so local people are enticed with familiar acts that have demonstrated international success; the strategy is to gradually build public appetite by importing commercial shows from Europe. The recent programming of Cirque de Soleil into the festival attracted 18,000 spectators. This is not quite a manifestation of supreme western hegemony but there is clearly a yearning from west Amman's elite to embrace western ideals of the arts, an ideal that might be less favourable towards the east of Amman.

Transparency or accessible public data when it comes to the fine details of government arts expenditure is somewhat lacking, although the consensus amongst local artists we encounter is that current funding is scarce,[13] inconsistent and not always spent effectively. Amman's developing museum sector has yet to ripen[14] as the current focus is towards promoting literature, heritage and various state sponsored festivals, leaving contemporary visual artists feeling somewhat undernourished. The gaps left by the state make privately run initiatives all the more critical.

Fortunately, there are autonomous initiatives that operate successfully using a mixed funding model. For instance, Ma3mal[15] 612 have independently created the Karama[16] Film Festival of Human Rights to reach younger audiences across Jordan by providing a platform to engage in global and cross-cultural discussions that address human rights issues through the medium of film. It is notable that the 2012 Karama Festival was funded by a range of sponsors that included the Open Society Foundation, Royal Cultural Centre in Amman, the Embassy of the Czech Republic, Arab Media and the Greater Amman Municipality, and the Goethe Institute in Amman. It is the latter sponsor that arouses most interest in terms of exploring what motives European cultural broker agencies might have when investing in foreign arts initiatives.

Culture brokers or Breakers?

The EU commission in Amman[17] is one of 130 EU delegations based in all corners of the world that act as the eyes, ears and mouthpiece of the European Union. As well as brokering trade agreements and securing regional stability, sponsoring culture is a key strand of the EU's remit. Of course, speculation around such cultural activities points to a prevailing suspicion that the EU is driven by self-interest rather than altruism. This rancour has been fuelled further since winning the Nobel Peace Prize in 2012, which prompted measurable consternation amongst EU critics.[18] Whilst the EU has transformed Europefrom 'continent of war' into 'continent of peace' the same cannot be said of its effects on the Middle East. Since the first wave of European External Action Service (EEAS[19]) appointments have taken up their positions their presence have been drowned out by popular revolutions across the Middle East and North Africa, exposing the challenge the EU faces in making its diplomacy the preeminent voice in the region.

'It is hard to survive as an independent artist in Jordan,' acknowledges Matthias Peitz in conversation, the EU's Officer for Communication, Culture and Political Affairs in Amman. He highlights the arts projects he part funded in 2012, which were essentially a film festival,[20] an independent dance festival, a Celebrating Europe Day and a Creative Industry Conference. Still, the jury is out as to whether projects are being handpicked for funding to parade like feathers in bonnet or whether they are serious about supporting sustainable long-term art initiatives in the region. We are issued with a glossy brochure[21] containing summary descriptions of a catalogue of projects EU has funded. The context, objectives and achievements are highlighted but when asked how the local, long-term impacts of these projects are evaluated the cool response comes across as laissez-faire.

There are a tight cluster of cultural relations institutes nested in Jordan: the British Council, Goethe Institute, Institut Français and Instituto Cervantes, which co-exist together under the umbrella of EUNIC (European Union National Institutes for Culture). In questioning the cultural impact of EU's role in Jordan, one must also look to the outputs of collaborative projects from these cultural relations institutes. A key initiative by EUNIC in response to the region's changing socio-political context is the EUNIC-MENA Creative Industries[22] project which aims to support the creative sectors in the MENA region to assert a key role in the process of democratic transition through cultural exchange.

Another strand of EUNIC's project is the mapping[23] of the creative industries in Jordanto help assess the value of these industries to the wider economy so as to encourage politicians to take the creative sector seriously and ultimately develop policies to push forward its agendas. The first phase of the mapping[24] was presented in November 2012 at the Creative Jordan – Platform for Visual Ideas; a conference[25] intended as a springboard for artists and cultural entrepreneurs to 'imagine their future'. Such a mapping project is a positive step in the right direction, assuming if the findings can be used to build a case to increase local funding for the arts. Since UNESCO's 2009/10 report[26] there has been no formal cultural monitoring, surveys or directories available on new or emerging cultural organizations in Jordan. Many creative practitioners will be anxious to see concrete developments transpire from EUNIC's initiatives.

It is probably no coincidence that the British Council's headquarters is located on Rainbow Street, down town west Amman – a vibrant cultural hub attracting locals and tourists alike. Marc Jessel, the British Council's Country Director, explains how his relational strategy relies on building trust[27] and being seen as accommodating towards local artists. An example of a live project he is backing is a programme that places art in unconventional spaces. Every Friday, different artists from Amman are invited to spray graffiti on the wall in front of the British Council. The project may not produce the most talented or original work but they are providing a visible platform some artists might not otherwise have.

Jessel has observed a changing context in the past three years during his placement in Amman. He has come to a realization that it could prove counter productive to support specific art forms if showcased to the wrong audience. Another concern is that audiences may become increasingly segmented over the next few years. Whilst he wants to target the hard to reach groups, he appreciates that introducing change at the grass roots level is difficult. Nevertheless, Jessel believes he can gain momentum by bringing onside those who are more likely to be receptive. Many of those likely 'supporters' happen to live and work and in west Amman. Jessel claims their scorecard analysis indicates the British Council arts programme reaches ten percent of Jordan's total population. Not all their work leads to deep engagement but Jessel appears content that their tentacles are extending across the capital towards the hinterland; hard to reach areas beyond west Amman. We get the impression that east Amman lies beyond the British Council's peripheral vision, as we would later encounter.

Although the British Council operates with full state permission, ironically their funded projects are not delivered in partnership with the Jordanian government. After these discussions, we were left wondering if the British Council should continue playing the foster parent role to abandoned artists or if their intervention deepens the gap by creating alternate dependencies within the Jordanian art scene. There is no national arts council to rely on, hence artists are not empowered to be totally independent unless they can self-fund in perpetuity.

When asked if there is scope of bringing Jordanian artists to the UK, a fleeting interest is sensed before Jessel swiftly recalls the ubiquitous problem of getting British visas for foreign artists – an exasperating barrier for mutual cultural exchange, though a perfect pretext to maintain the status quo. Mobility[28] is a major factor that is hindering progress. In a country where travellers rely heavily on flight and obtaining a visa is a universally tricky issue for cultural practitioners (the application process is complicated, protracted and expensive), many local cultural practitioners are left feeling trapped.

Postcards from Philadelphia[29]

Our work reflects our challenges, our thoughts, our dreams, our inspirations of our daily life and the changes that we are going through. So this impacts the work and makes it related to the region. Location doesn't change my product or my thought, for you carry your identity within. I could be making the same art, even if I resided in London.

- Dina Abu Hamdan, Director of Zakharef in Motion, Amman.[30]

A significant quantity of residents in west Amman have access to private education and opportunities to study abroad, tending to a more liberal outlook in tune with trends in western contemporary art. Reputable artists that have successfully emerged from Jordan include Jerusalem-born abstract painter Nabil Shahadeh and architect turned designer, Rasem Badran (also born in Jerusalem), who has recently taken up the pursuit of Islamic art in the footsteps of his late father, Jamal Badran. Celebrated artists like these have the virtue of having their work showcased at the National Gallery of Fine Arts[31] or the Darat al Funun art space[32]. Remarkably, there are alternative venues operating independently without any public funds that have won moral support from established artists like Shahadeh and Badran. For instance, The Studio is an art and installation space for local independent artists run solely by young female artists; we were privileged to witness their determination, talent and entrepreneurial spirit. Their latest exhibition featured a selection of Philadelphia 'skateboard art' as a reflection of the youth culture taking off in the streets of Amman.

Upon asking if they would seek funding from the British Council to support their work we gauge a firm reluctance. These artists are not willing to compromise on the integrity of their work, nor are they interested in their ideas being conflated with political agendas. Our insight into the British Council and EU confirms that 'soft power' is seriously in action in Amman. There are no grand statements; no obvious muscling their way in to overpower another culture, but there is a subtle sense of the 'Western world' knows best. And the 'Western World' certainly still has the cash, which is helping get their message across – especially in west Amman. It's easy to see why many cash-starved contemporary Jordanian artists resort to these international cultural organizations as their only support. A desperately needed financial support that locals feel their government is not yet providing. Formidable private sponsors such as insurance company Al Nisr Al Aarabi,[33] are starting to invest in the local art scene, but competition for such sponsorship is fierce.

Western culture continues to be heavily exported into Jordan whilst there are glimpses of how the flow of home-grown art production is veering out of Jordan also. Composer Nasser Sharaf's world-fusion style rock opera based on the historical and mystical city of Petra, Petra Rocks,[34] is arguably Jordan's first major cultural export of it's kind. The musical is set to begin a tour through the Arab world later in 2013 starting in Algeria, Dubai, Qatar and Kuwait, before returning to west Amman. This live project is bringing together the best local talent from across the creative sector, proving Jordan has the innate capability to produce and tour world-class performances without propping from cultural broker agencies.

The Other Side of the Rainbow

Despite concerted attempts to revitalize[35] downtown Amman (part of east Amman) higher rates of unemployment and poverty along with lack of infrastructure and cultural programmes correlate with a lower engagement with the arts in the locality.

Jordan is thought to be host to over two million Palestinian refugees, the largest number compared to any single country in the world – making nearly half if its population of Palestinian origin[36] and a growing 'silent majority'[37]. A higher concentration of refugees lives in camps situated in east Amman. Palestinian legacy is a particularly significant factor in the process of developing a common Jordanian national identity. Jordan, like the rest of the Middle East is a patriarchal state. Citizenship is currently determined by the Father's origin of birth. So when a Jordanian woman marries a Palestinian man – which is often the case – their children are automatically denied Jordanian citizenship. This frustrating dilemma is visually expressed impromptu on the street walls[38] in part of east Amman through the medium of graffiti art – a symbolic demonstration that vernacular artistic expression is inextricably linked with cultural identity and a layperson's campaign vehicle for legislative reform.

One striking example of a community initiative based in east Amman that is using the arts to promote social inclusion and regeneration is the Ruwwad[39] Institute. Based in the impoverished Jabal al-Nadif (Clean Mountain), an otherwise marginalized community incorporating a Palestinian refugee camp is proving to be fertile ground for an organic arts movement where the arts form part and parcel of daily life.

Ruwwad (Pioneers) is a privately funded initiative that operates directly at the grassroots level to create constructive change to education, job-creation, child development and access to opportunities. Ruwwad is able to serve local needs through working in effective partnership with the Jordanian government (the 'Big Society' model).

Public consultation with the neighbourhood determines which projects to prioritize, including projects around public services such as children's library, a legal fund, creative arts workshops, debate clubs and curriculum enrichment classes that are especially valuable to girls and young women. This approach helps to build leadership in the community through promoting learning based enquiry and developing crucial skills in critical thinking. Ruwwad's operating model is to provide university and college scholarships to students from the community, and in return the students give back a set number of voluntary hours to work with the various programmes.

Without doubt, this indigenous grassroots diplomacy is winning the hearts and minds of the people and facilitating positive change in the neighbourhood. The programme graduates we spoke from Ruwwad are a remarkable manifestation of youth empowerment, fuelled with ambition, positive energy and practical knowledge. The visual arts have been instrumental to enabling progress in a way that genuinely makes sense to the community. There is local optimism about the sustainability of Ruwwad, which should continue to bear fruit.

Amman may appear divided, but is actually one complementary whole, with a thick band of human fibre running across it. I urge everyone, Ammanis and visitors alike, to step out of their comfort zones and tap into it. It is a journey that will unify your brain and feed your soul. A feeling of oneness, built on diversity, is what Amman is most in need of, to grow but remain rooted in its human and cultural heritage.[40]

- Raghda Butros, Founder of Ruwwad

Soft Power vs. Universal Cultural Empowerment

We have observed how the precarious state of the arts in Jordan is embroiled in both nation-global and local divides. Amman is a city in an east/west divide that is also mediating the influences of the western world on local art production while local art production struggles to find ways to manage, fund and promote the arts in Jordan, from both the institutional and governmental levels, as well as the local practitioner.

The vacuum of bona fide cultural exchange programmes brokered from within Jordon is deeply surprising considering the common advantages to be gained. Given that the current state of cultural exchange between east/west Amman is far from attaining equilibrium, the EU and British Council could offer better value by funding cultural exchange initiatives that permeate across east/west Amman and enable art projects to flow out from Jordan towards the western world, where access to arts from the region is limited, if not virtually non-existent. Emerging Jordanian artists would benefit from the creation of more overseas student exchange programmes, international creative fellowships and opportunities to take up artist residencies abroad.

Cultural practitioners visiting Amman or seeking future collaboration with local artists can transcend the formal cultural diplomacy model by forging new professional contacts themselves, enabling new opportunities for dialogue and cultural exchange on mutual terms. We are left in no doubt that genuine cultural exchange at the local level is more respected and fruitful than conventional cultural diplomacy. We hope to witness a movement away from the stale western hegemony of soft power towards a fresh paradigm that enables universal cultural empowerment. Perhaps creative entrepreneurs abroad are de facto cultural diplomats?[41] In any case, cultural practitioners have both the potential and opportunity to help to bridge the East/West divide both within Amman and across the wider world.

Acknowledgements

With special thanks to International Clore Fellows, Dina Abu Hamdan and Jo Mangan.

Footnotes

[1] Soft power is the ability to influence the behaviour of others to get the outcomes you want: Joseph Nye, Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics (New York: PublicAffairs, 2004).

[2] See the DEMOS report by John Holden: http://www.demos.co.uk/publications/culturaldiplomacy

[3] The Clore Leadership Programme (www.cloreleadership.org) is an initiative that provides intensive development in the UK to a cohort of established practitioners from the creative sector each year. Clore Fellows are selected from across the UK and abroad. Chevening Scholarships are the UK government's global scholarship programme, funded by the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (http://www.chevening.org).

[4] Visitors are frequently made to feel welcome by locals using this phrase.

[5] Barakat Awajan is the newly appointed Minister of Culture now in place.

http://www.culture.gov.jo/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=37&Itemid=81&lang=ar

[6] Royal Film Commission is Jordan's first centre for the audio-visual arts. The Film House aims to develop the audio-visual industry while encouraging the emerging film culture in Jordan. It has the benefit of being funded directly from the Prime Ministry. http://www.film.jo/?q=node/227

[7] 'Filmmaker explores Amman's Real, Imagined Divides,' Sahafi, 8 May 2010 http://www.sahafi.jo/arc/art1.php?id=357734d0883784f5ed697f8a5ed77b5aa28ecfd3.

[8] The documentary screened by and Al Jazeera in 2009 Royal Film Commission in 2010 is available to watch online: http://www.ikbis.com/shots/254818

[9] R.B. Potter et al., '"Ever-growing Amman," Jordan: Urban Expansion, Social Polarisation and Contemporary Urban Planning Issues,' Habitat International 33 (2009): 81-92

http://arlt-lectures.com/jordan-amman.pdf

[10] James J. Zogby, 'Bridging the East-West Divide,' The Jordan Times, 28 January 2013 http://jordantimes.com/bridging-the-east-west-divide.

[11] Agence France-Presse, 'Jordan's East vs West Divide Highlighted in Satire,' The National, 17 July 2012 http://www.thenational.ae/news/world/middle-east/jordans-east-vs-west-divide-highlighted-in-satire#ixzz2Tvp3OEbz:"The play brings to the stage with subtle sarcasm the rifts between East Bank Jordanians and those of Palestinian origin, or West Bankers" :

[13] Dina Abu Hamdan, The Cultural Experience in Jordan 2012, report commissioned by the EU, Amman.

[14] Amman has several new and emerging museums that deserve a special focus in a separate essay.

[15] Ma3mal 612 (Think Factory) is a collective of artists and filmmakers who seek to produce Art of an Avant Garde nature that works to make an impact and change upon civil societies in our region and the globe.

[16] Karama (dignity) promote screen arts that explore human rights issues and open democratic dialogue about human rights. See: http://karamafestival.org/new/

[18] See: 'Nobel Peace Prize goes to War-Makers, While Peacemakers are Shunned,' Huffington Post, 18 October 2012 http://www.huffingtonpost.com/dan-kovalik/nobel-peace-prize-winners_b_1968088.html and Charlemagne, 'The EU and the Nobel Peace Prize: Hmmm,' The Economist, 12 October 2012 http://www.economist.com/blogs/charlemagne/2012/10/eu-and-nobel-peace-prize.

[19] EEAS staff come from the European Commission, the General Secretariat of the Council and the Diplomatic Services of EU Member States. See: http://www.chathamhouse.org/research/europe/current-projects/external-action-service-and-future-european-diplomacy.

[20] '24th EU Film Festival Underway in Jordan Under the Theme "Transitions"', EU Neighbourhood Info Centre, 1 October 2012 http://www.enpi-info.eu/medportal/news/latest/30396/24th-EU-Film-Festival-underway-in-Jordan-under-the-theme-%E2%80%9CTransitions%E2%80%9D.

[21] 'Culture and Development: Action and Impact'. Brochure available online: www.culture-dev.eu

[22] The Euro-Med Forum on Creative Industries & Society (http://www.eunic-online.eu/fr/node/559) is intended as a meeting point for key players in the creative sector.

[23] BOP Consulting has been commissioned to conduct this research project in collaboration with local experts from the cultural sector.

[24] Parallel to the mapping, an online platform for creative industries in Jordan is being developed by Nadine Toukan and Yusuf Mansur: http://urdunmubdi3.ning.com/

[26] 'A Survey of Cultural Practices in Jordon 2009-10,' UNESCO http://www.scribd.com/doc/83030324/Unesco-Cultural-Survey-Jordan-2011

Produced primarily through interviews with leading individuals and institutions in the cultural field and was the result of a cultural mapping of Jordan undertaken by UNESCO Amman.

[27] 'Trust Pays: How International Cultural Relationships Build rust in the UK and Underpin the Success of the UK Economy,' report, British Council http://www.britishcouncil.org/trustresearch2012.pdf

[28] Jordon is enclosed in all directions; the cordoned-off Syrian border and the Iraqi and Israeli borders which are equally non-porous. The driving ban on women in Saudi Arabia means that unaccompanied Jordanian females cannot cross those borders by car even if there were artistic opportunity to do so.

[29] Zakharef in Motion started as a dance festival and has recently blossomed into the Zakharef LAB producing local work with the ultimate aim to perform regionally and internationally. See: https://www.facebook.com/zakharefinmotion

[30] Philadelphia (meaning the 'The Brotherhood Love') is the ancient Greek name for the City of Amman.

[31] National gallery of fine art is a primary destination to savour contemporary Jordanian painting, sculpture and pottery. Contemporary art is showcased from around the Middle East and the greater Muslim world. See: http://www.nationalgallery.org

[32] Darat al Funun is a home for the Arts and the artists of Jordan and the Arab world. See: http://www.daratalfunun.org/main/index.html

[33] 'Al Nisr Al Arabi Insurance Company sponsors the 5th Edition of Zakharef in Motion Dance Festival http://www.albawaba.com/al-nisr-al-arabi-insurance-company-sponsors-5th-edition-zakharef-motion-dance-festival-second-year

[34] For a trailer of Petra Rocks see: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TlQZU62eK_k

[35] "In 2000, the Municipality of Amman moved into new buildings designed by the two best Jordanian architects (Jafar Toukan and Rassem Badram) in Ras al‑Ain, in the heart of the city, in order to make the municipality equally accessible to residents from the East and the West of the city. The al-Hussein Cultural Centre was built in what was formerly the playground for children from Jabal Amman and Jabal Nadhif, at the source of the Sayl Amman. On the far eastern side of Ras al-Ain, near the entrance to the souk, the new National Museum has been under construction since 2006 and will be inaugurated in late 2010, helping to reinforce the importance of the historic centre. Artists and cultural activists are trying to build bridges between the two parts of the city. Raed Asfour opened the al-Balad theatre in February 2005 on the slopes of Jabal Amman, at the top of the steps that climb up from the downtown post office, "to build a bridge between the East and West of the city" and make art accessible to the most underprivileged (Ababsa 2007, 236-240)."

Myriam Ababsa, 'Sustainable Architecture and Urban Development,' conference paper, Second International Conference on Sustainable Architecture and

Urban Development, CSAAR, MPWH, University of Jordan, Amman, July 2010 http://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/docs/00/46/75/93/PDF/CSAAR-Ababsa-Upgrading_Policies.pdf

[36] Reported by UN Refugee agency. See: http://www.unrwa.org/etemplate.php?id=100. There are also tens of thousands of Iraqi refugees who have fled to Jordan.

[37] Chris Phillips, 'Silent Majority: Palestinian Jordanians and the search for identity,' Ideas Today 1 (2009): 6-10 http://www2.lse.ac.uk/IDEAS/publications/ideasToday/01_SilentMajority.pdf

[38] For further insight into graffiti art in the Middle East, see: 'Walls that Speak,' Al Jazeera, 3 April 2013 http://m.aljazeera.com/story/20134311513909921

[40] Raghda Butros, 'One Amman,' Be Amman website, 2012

[41] Colin Hicks, 'Cultural Entrepreneurs: the New Diplomats?' blog entry, Cultural Diplomacy: How Governements Manipulate the Soft Power of Artists blog, 2012 http://thelondonembassy.blogspot.co.uk/2012/09/cultural-entrepreneurs-new-diplomats.html