Essays

Rethinking National Archives in Colonial Countries and Zones of Conflict

The Israeli-Palestinian Conflict and Israel's National Photography Archives as a Case Study

Zionist photography archives of the State of Israel – civil and military – reflect pre-state and state activity and policy in the field of photography, and form part of a larger and more powerful institutional system. These archives are not neutral and are connected to a national ideological system that loads them with meaning and a Zionist worldview. The way they are structured, function, collect, catalogue and preserve materials, and their policies of exposure or censorship, is driven by a national ideology, serves its fundamental norms, values and goals, and helps in constructing its symbols and language. As in other cultural and civil systems in Israel, and similar to the mechanisms of pre-state or state Zionist propaganda, official photography archives are also recruited for establishment benefits, and assist in shaping public opinion, attitudes, content and worldviews. They are under absolute sovereign control, and represent one brick in a large systematic structure, of a control mechanism that oversees the construction of meaning.[1] The ideological activities of these photography archives are inbuilt, and affect the representation of the conflict and its evolution in the public consciousness.

In addition, photography itself serves as a vehicle for establishment power mechanisms based on systems of oppression, and is used as a tool to convey ideology and to manufacture narratives, myths and national terminology. National state bodies, including propaganda departments, pre-state military groups, photography archives and others, subjected photography and its use to their interpretation and worldview since the inception of Zionist photography in the early twentieth century, when it was used to market the Zionist idea of establishing a Jewish state,[2] and continue to do so to this day.

In contrast to photography archives that operate as entities that collect information from outside sources, most of the national photography archives in Israel were established, along with photography departments that actively ordered photographs from photographers in the service of the institutions they represented, for national benefits. Therefore, these archives also engaged in an initiated, informed and conscious dissemination of photographs for these purposes. In other words, the long-term conservation of photographs in Israel's national archives is the final stage of institutional involvement in the field of photography. In various studies, I have discussed the ideological strategies that accompany the activities of these mechanisms and systems, from control of the production process of the single photograph (what to photograph and what not, when, how, what to include in the photograph and what to avoid, which photographer, who owns the negative and its copyright etc), to the structure of the archives and how they operate in preserving and distributing the photograph in the public sphere, while loading it with meaning and content (how the material is classified and edited, the terminology that accompanies the photographs, the selection of what is marketed and distributed and where, what is concealed and more).[3] In general, these mechanisms regulate photography, organizing and managing it according to strict rules and codes in order to construct a one-sided Zionist national worldview that is slanted and enlisted.

The national character of state Zionist photography archives is overt and visible. For example, the book and the exhibition Six Days and Forty Years (2007) deal with the way Israeli institutional bodies shaped the occupation of the West Bank, Gaza and the Golan Heights as moral and beneficial to Israeli society and the state after the Six Day War in 1967.[4] In this essay, I would like to extract additional layers of information, meanings and characteristics that are not apparent from these archives. Derrida, who studies archives as geological or archeological excavations, addresses its logic and semantics. He describes the way 'quasi-infinity of layers, of archival strata … are at once superimposed, overprinted, and enveloped in each other,' and are stored, accumulated and capitalized. 'To read … requires working on substrates or under surfaces, old or new skins.'[5] This reading, especially in areas of conflict, allows for a wide range of interpretation and analysis that often contradicts the primary aim of state archives and their national character. Since the official role of national photography archives is representative and apparent, I will show that it is possible – even obligatory – to extract additional layers of knowledge, content and meaning that undermine the original structure of the archive and challenge its contents and national objectives. This information, largely buried in photography archives, makes it possible to crack their underlying nature and create an alternative to establishment perceptions. However, these additional layers can be deciphered and liberated only after neutralizing the biased aspects of the archives. Isolating their ideological characteristics, and 'cleaning' and freezing their national bias, allows additional contextual layers – often contrary to the nature of the archive – to be freed.

In 'Reading an Archive', Allan Sekula argues that the archive has the semantic availability to change over time, and to be 'appropriated by different disciplines, discourses, "specialists"'. They are open to other interpretations by new agents, and thus 'new meanings come to supplant old ones, with the archive serving as a kind of "clearing house" of meaning'.[6] Or, as stated by Derrida, 'radical destruction can again be reinvested in another logic, in the inexhaustible economic resource of an archive which capitalizes everything, even that which ruins it or radically contests its power: radical evil can be of service, infinite destruction can be reinvested in a theodicy.'[7]

Ann Laura Stoler, who addresses the writing of colonial history, discusses the critical and conceptual potential to enable a fluidity of knowledge according to a new vocabulary of words and concepts. In an essay that focuses on the writing of colonial history in France, drawing on Foucault, she discusses how 'categories are formed and dispersed, how aphasics disassociate resemblances and reject categories that are viable…produces endless replacements of categories with incomprehensible associations that collapses into incommensurability.'[8] Stoler describes historical writing as 'an active voice' dealing only partially with the past. It allows 'differential futures' that reassess the resilient forms of colonial relations. In an essay dealing with the building of postcolonial archives in South Africa, Cheryl McEwan demonstrates how, after the ending of apartheid, civilian and government entities established archives devoted to portraying its policies and their devastating consequences, and to give voice to the population particularly affected by them, such as black women. McEwan discusses the importance of building alternative post-colonial archives based on seemingly marginal materials, and the need to include them in national projects for the purpose of 'remembering and notions of belonging.'[9] But, unlike the situation in South Africa where, as McEwan points out, its initiated national projects have a latent radical potential, and can challenge the national representation of the past through subversive projects funded by institutional bodies, in Israel these processes are still in their initial stage,[10] and also provoke institutional and public objections.[11]

Palestinians in Zionist Establishment Archives

Writing an alternative history of subjugated populations represented in photography archives is made possible by discussing the power relations and violence that characterizes them. Deciphering these archives' repressed characteristics will broaden the understanding of their role in conflict areas, and offer new models for reading and interpretation. Over the years, Israel and its pre-state and state institutional public, military, national, and private archives became an important reservoir of information about the Palestinians in the first half of the twentieth century.[12] By reviewing the representation of Palestinians in Israeli photography archives, and dealing with the paradox whereby a state that is in a long and continuous national conflict with another people – a state that occupies and controls them – demonstrates how these archives developed into a significant source for historical and cultural materials on Palestine, not to mention other materials as well.

Furthermore, the fact that the occupying Israeli society also preserves parts of Palestinian historiography – visual and written – shows that the control is not only geographical, but extends also to awareness, identity, memory, as well as cultural and historical spheres. The dependence the ruled have on those who hold power for writing their history, and the sophisticated methods used by the occupiers to push materials of the occupied to the margins, are some of the mechanisms that need to be 'cracked' in order to build this understanding. Thus, I will map sources of information about Palestinians in national, institutional Zionist photography archives in Israel, and propose a new role for them in the public sphere.[13] I have discussed some of these sources in the past, but this essay gathers the various information sources together, characterizes and maps them, and indicates the phenomenon.

The national photography archives under discussion are composed of two kinds:

1. Civil establishment photography archives that serve national goals – Government Press Office – National Photo Collection, The Central Zionist Archives, Israel State Archives, Jewish National Fund Archive, and The National Library of Israel.

2. Military photography archives – pre-state and state archives that serve military and national security interests such as the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) and Ministry of Defense Archives, the Hagganah Archive and the Palmach Archive.

When discussing the representation of Palestinian history as reflected in these archives, several factors must be considered:

1. In Palestinian visual historiography there are many missing chapters. Countless photographs and visual archives were looted, plundered, destroyed or lost during the 1948 war and subsequent wars, or as a consequence of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.[14] Palestinian culture and history fell victim to the national conflict, and for the last two decades, Palestinian and Arab researchers have worked to complement parts of this physical loss, and to structure the Palestinian historiography.[15] However, many of the missing chapters are stored and hidden in Israeli archives that allow limited access to Palestinian and Arab researchers, and to a degree, to Israeli critical researchers.

2. The activities of the National Archives with regard to others, including Palestinians, incorporates in many cases, two kinds of violence:[16]

2a. Documented physical violence – this is the visible aspect of the violence directed toward the Palestinian population, and is present in national institutional photography archives and others.[17] It includes, for example, theft and appropriation of land, exile, martial law and a military regime.[18] The discussion about the visible aspects of violence in various projects draws largely on Walter Benjamin's, Critique of Violence, which analyses violence and power exercised by a ruling authority by virtue of the law.[19]

Joseph Pugliese claims that the documenting of scenes of violence becomes an instrument of violence itself. In an essay dealing with archives of photographs of tortured detainees, and of soldiers who tortured detainees in Iraq's Abu Ghraib prison, he points to the photographic act and its physical outcome – the photograph – as part of the fascist mechanism that testifies to the abuse of human rights. For example, the humiliation suffered by the abused detainee doesn't end with the act of degradation itself, but with its documentation, which perpetuates it forever. Thus the camera too becomes an instrument of torture. Pugliese demonstrates how archives – 'shadow archives' as defined by Allan Sekula [20] – also become part of the American colonial mechanism of violence made visible through the representation of the oppressed body. He describes how these archives are dominated and controlled by a visual regime, and the way meaning is re-framed in the context dictated by different mechanisms of power.[21]

2b. Functional violence inherent in archival structures – this violence is embedded and entrenched in the structure and operations of national, institutional archives and in their physical and fundamental actions. The power applied and it's structure, normally concealed, is an integral part of institutional mechanisms based on ideological, repressive aspects. It is expressed in the formation of archives and their mode of operation, as well as in their ethical functioning – their underlying objectives and norms – and in the laws and rules that regulate the activities of gathering, preserving, archiving and distributing. This type of violence is usually intrinsic and not apparent, and dictates what to document and collect, and what to preserve, although is sometimes wrapped in visible aspects of physical violence, such as looting and booty, mentioned above. These moral and functional aspects are quite evasive and their aggressive aspects are generally camouflaged, so the need to bring them to public awareness requires exposure and knowledge.

Military and security materials in Israeli archives concerning Palestinians largely reflect the direct and indirect violation of human rights. The direct violation of human rights originated mainly with a variety of activities whose objective was intelligence gathering for military and operational purposes, most of them based on the dual operation of power relations: on one hand the method used by units and military archives to gather information (booty, looting, secret and prohibited copying of material from other archives, intelligence gathering by various means, etc), and on the other, the management practices of archives and their limits on exposure of certain materials to the public (censorship and restrictions on viewing). The indirect aspect of human rights violations includes, for example, the denial of Palestinian existence. This too can be classified as functional violence. It is reflected in the way pre-state civil bodies, such as the Jewish National Fund and The National Foundation Fund, acted to promote Zionist propaganda in the country and abroad, excluding the Palestinian entity from the regional lexicon, and omitting their presence in the public sphere. These bodies were engaged in constructing a moral justification for Jewish settlement, describing the land as empty, ruined and deserted, and Zionist settlement as an act of redeeming the land. Ignoring the Palestinian population and its rich economic, educational and cultural life, was intended to serve national marketing objectives, and involved the use of force.[22] The article focuses mainly on this type of violence, inherent in the archives, and less on the overt and documented violence.

In the process of analysing materials taken by force from Palestinians and information gathered about Palestinians in photography archives, I encountered two different types of data: direct information, and information that needed to be extracted from the archive in which this paper will focus. The category of information correlates, to a certain extent, with the type of violence involved in collecting these materials:

Information that needs to be extracted from the archives

Much of the information about Palestinians stored in photography archives is catalogued, accompanied by texts and published in frameworks that blur the Palestinian context. More than once over the years, I had to liberate these connections, pointing out their innate information, which allows them to be read and interpreted in a manner at variance with that enforced by the archives. The first time I offered to strip photographs connected to Palestinian existence from their imposed Zionist national context, was in the essay, 'The Absent-Present Palestinian Villages',[23] where I suggested the need to decipher the contradictory meanings possible to read in the archive that occasionally oppose their nature and visible intention, and to crack their facade. The essay discusses the representation of displaced Palestinian communities in Israeli collective consciousness, as reflected in the Government Press Office – National Photo Collection attached to the Prime Ministers Office, and the Photography Archive of the National Jewish Fund. It deals with villages whose residents fled or were expelled in the 1948 war, and were prevented from returning to their homes by the Jewish state. Jewish immigrants who arrived in the massive waves of immigration between the years 1948–1950 repopulated most of these villages. Some of them were destroyed by the Israeli army, with the aim of preventing Palestinians from returning, and in order to erase them from the map and from public consciousness and eliminate them from memory.[24] In a book that discusses the birth of the Palestinian refugee problem, Benny Morris demonstrates that at first, in 1948, the State established settlements outside the built-up area of displaced Arab villages, while many of the settlements that were founded in 1949 and later, were established in the villages themselves, since it was quicker and less expensive to rehabilitate them than to build a new settlement.[25]

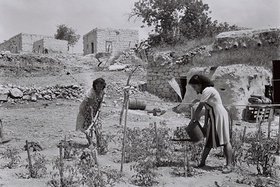

The photographs documenting Jewish settlement in Palestinian villages are the only remaining evidence of these communities, moments after their physical and legal possession, and just before losing their Palestinian identity and becoming Israeli. Although the original inhabitants were exiled – they were considered Absent-Present by the Israeli state,[26] and there is no record of the physical violence used against them – many of the photographs show entire villages, homes and fields, making it possible to reveal what Israeli collective memory has repressed: the tragedy experienced by the Palestinian population. Over the years these villages have altered their structure, character and identity. In areas where Palestinian lands were transferred to Jewish hands, methods of farming, crops and the rural structure of the villages began to change; the distinctive landscape of Palestinian agricultural settlement developing characteristics of Jewish agricultural settlement. The photographs show the absorption of Jewish immigrants in the new state on the ruins of the Palestinian entity, and thus have two different ethnic and geographical features that combined, create a new reality: on one hand, the Palestinian village with its distinctiveness, style, and methods of cultivating the land, symbolizing the missing Palestinian entity, and on the other hand, new settlers, engaging in daily activities that symbolize the normality of Jewish settlement – sewing, embroidery, study, yard work and so on.

These photographs were created as part of Zionist propaganda that sought to document the proliferation of Jews in the young country as a continuation of the pre-state Zionist ethos of kibush hashmama (redeeming the land), and to bypass the UN resolution allowing the refugees to return home. Supposedly, these are pure Zionist photographs: they were used to document the activities of the Jewish National Fund and the State of Israel in settling the land, and as part of its public relations and fundraising efforts. According to this standpoint, Israel's very existence was conditional on Jewish possession of most of the land that could be controlled and settled. Thus, the official appearance of the photographs is entirely Zionist. However, this stance did not confront the ethical and legal questions that should have arisen, questions that are in fact expressed in photographs that appear seemingly innocent. The absent become present via the land, the houses and the vegetation, and those present appear largely foreign in the landscape. In many instances the Jewish immigrants are dressed in clothes from their country of origin, and their alienation from the local land hints at the identity of the people who worked it, who lived in the photographed houses and were an integral part of the environment. Above all, the combination of different ethnic and architectural characteristics seen in each image indicates the people who were part of the landscape and are now absent. Indeed, whoever ordered the photographs, like the majority of the Israeli population, was blind to the Palestinian entity, wishing to present only the Israeli human landscape and the kibbutz-galuyoth (ingathering of the exiles) of new Jewish immigrants from all over the world. In spite of their original objective, after liberating the photographs from their propaganda aspect, the absent become visible, the missing become present, and the forgotten become speakers of memory that brings to life the map of the country in its previous configuration. Thus, regardless of their original intention, the Zionist photographs become the mouthpiece of the Palestinian catastrophe.

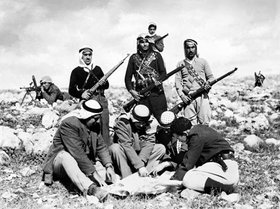

Another example is from the field of military photography. Jewish intelligence bodies began collecting information about the Palestinian entity before the establishment of the State of Israel, marking the beginning of military Jewish photography in Palestine. Soldiers, scouts and Jewish pilots collected data for operational intelligence which in due time would provide assistance for future occupation of the Palestinian population, and for controlling and monitoring the population after occupation. In this way information was collected about Palestinian communities and those Palestinians who took part in resisting the Zionist enterprise. This intelligence activity, which began in the late 1920s, became institutionalized and organized in the 1940s in its various fields, among them the field of photography. Direct photography of Palestinian targets – aerial photographs, photographs from the ground, 'village files'[27] and a photographer disguised as a Palestinian, were among the methods used by Jewish military bodies to collect information about the Palestinian community and Palestinian existence in Palestine.[28] However, these bodies also used other methods, such as looting of photographs and archives from Palestinian bodies and individuals, looting of images during battle, and duplication of material from British sources. The information gathered about Palestinian villages, towns and populations became a large reservoir of knowledge, with a historical and cultural value that expropriates the visual data from its limited function as a military document. The visual information taken on the ground and from the air, as well as the textual information collected by Jewish scouts and Palestinian informers, was detailed, extensive and comprehensive, and dealt with many aspects – from geographic and demographic data to economic and social.[29] For example, aerial photographs taken by the Palmach Squadron from late 1946 were part of a network of initiated and organized intelligence gathering, documenting the many Palestinian villages in preparation for a future national conflagration or war, or in order to occupy and control them. Aerial photography assisted in studying the area and in constructing topographical maps for future military aims: it included details of the landscape, and gave the most up to date depiction of the terrain, including all the latest changes, allowing control over territory that was not reachable in any other way.[30] These photographs served a military operational purpose before and after 1948 (as part of the control over the Palestinian population during military rule), but today they can help reconstruct the geographical distribution of Palestinians before 1948, supplying a detailed description of every locality. From an historical perspective, these photographs, most of them from 1947–1948, are the last comprehensive and systematic documentation of Palestinian settlements before they were destroyed or resettled by Jewish immigrants, making it possible to build a map of the country from a Palestinian perspective. Paradoxically, even though photographed by Israeli military bodies in the service of operational national Zionist aims, and in spite of their tendentious nature,[31] they now, in fact, offer much information on the destruction of the Palestinian entity.[32]

Afterword

My research over the years dealt with the question of tyranny that characterizes the activities of Israel's national, institutional photography archives. I discussed the power relations that shaped them and the significant role they played in determining the perception and writing of history. Derrida points to violence as one of the main features inherent in the archive, embodying governmental information/power relations.[33] These aggressive relationships are intensified in a country where two peoples, occupiers and occupied, live in a national conflict and are present, for example, in the way institutional archives control both the national treasures of the vanquished and knowledge of his history and culture. Pointing out the overt and covert mechanisms in these national institutional archives by stripping away and exposing their inherent national bias, lays the foundation for building an alternative, layered database, different from the one-sided worldview that characterizes them. This enables the original purpose of the archives to be undermined, and in the words of McEvan, put through a process of democratization.[34] However, while in South Africa civil organizations and government are aware of the importance of establishing postcolonial archives (post-Apartheid), in Israel the situation is different. Although in recent years additional studies have started to breach this national cover, exposing excluded areas of knowledge and research, in Israel they still exist on the margins and there is ample room to read archives in a way that penetrates their facade of physical violence. It is also necessary to deconstruct the archive's structure, and to propose alternative mechanisms of reading, interpretation and criticism in addition to those discussed in this essay.

The voice of the subjugated is not entirely absent from national, institutional archives in Israel, but exists in an emasculated and misleading form. In this essay, I wanted to raise the possibility of hearing these voices seemingly missing from the archives. Freeing the national archives from their chains, and the construction of an independent memory and history – by challenging the national database and providing a platform for Palestinian voices and the return of their materials – are the first steps in establishing alternative national archives in Israel. However, stripping away their outer wrapping does not replace the importance of hearing the voices of the oppressed, learning their history and restoring their ownership and rights.

An extensive version of this paper was presented in the conference Lifta – Last Call, Bezalel, Academy for Art and Design, Jerusalem (July 2013) and in Reality Trauma and the Inner Grammar of Photography, Israel: The Shpileman Institute of Photography, 2013 (Hebrew).

[1] Rona Sela, Photography in Palestine in the 1930s and 1940s (Israel: Hakibbutz Hameuchad Publishing House, 2000); Rona Sela, Six Days Plus Forty Years (Israel: Petach Tikva Museum of Art, 2007) and Rona Sela, Made Public – Palestinian Photographs in Military Archives in Israel (Israel: Helena Publishing House, 2009).

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Sela, Six Days Plus Forty Years.

[5] Jacques Derrida, Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression, trans. Eric Prenowitz (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998), 22.

[6] Allan Sekula, 'Reading an Archive: Photography between Labour and Capital,' The Photography Reader, ed. Liz Wells (New York: Routledge, 1983/2003), 444-445. In 'The Body and the Archive' Sekula, drawing on Foucault, points to the double system of photographic portraiture 'a system of representation capable of functioning both honorifically and repressively.' This double operation 'extends, accelerates, popularizes and degrades' the traditional functioning of the bourgeois self, at the same time indicating the repressive social relationship with regards to the other, which enables the 'social body' to be defined. Allan Sekula, 'The Body and the Archive,' October 39 (1986), 6-11.

[7] Derrida, Archive Fever, 13.

[8] Ann Laura Stoler, 'Colonial Aphasia: Race and Disabled Histories in France,' Public Culture 23.1 (2011): 153-156.

[9] Cheryl McEwan, 'Building a Postcolonial Archive? Gender, Collective Memory and Citizenship in Post-Apartheid South Africa,' Journal of Southern African Studies 29.3 (2003): 739-757.

[10] In recent years some researchers as an extension of their political views, have begun to make critical use of national archives, for example: Chava Brownfield-Stein, 'On Ghosts Reappearing from behind One Famous War Photograph,' Sedek Magazine 1 (2007): 50-58; Ariella Azoulay, Act of State (Israel: Etgar, 2008) and Ariella Azoulay, Constituent Violence, 1947-1950 (Israel: Resling Publishing, 2009). However, these researchers did not point to the subversive potential in national archives and the possibility of formalizing alternative archives based on them.

[11] Thus, for example, when I was the chief curator of the Haifa City Museum I planned to show an exhibition, which aimed to deal with the dramatic changes that occurred in the country in 1948 – both the Palestinian catastrophe and the building of the Jewish state on the ruins of the Palestinian entity. The idea that I would expose the Palestinian tragedy and narrative was perceived as controversial and I was fired from the museum. Dani Ben-Simhon, '1948 Haunts the Haifa Art Museum,' Challenge, A Magazine Covering the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict 108 (March-April 2008): http://www.challenge-mag.com/en/article__207.

[12] Not only in terms of quality but in terms of content. Because of censorship laws and restrictions on viewing in Israeli law, that enables archives to avoid disclosing material for 50 years from its date of issue most of the materials relating to the Palestinians currently opened for inspection and use are from not later than the 1950s. Sela, Made Public.

[13] With one exception, which relates to textual archives, the essay deals with national, institutional Zionist photography archives, and not private collections holding Palestinian collections and photographs. The latter reflect the manner in which individuals in a society internalize codes of institutional power systems, and how practices of power permeate the private and civil sphere. Sela, Made Public.

[14] For example, the archive of the photographer, Chalil Rissas, whose shop was looted after the war, or photographs from World War I, pillaged from the Nashashibi family in Jerusalem. Ibid. Another type of loss comes from the plunder of Palestinian books. Gish Amit, 'Salvage or Plunder? Israel's "Collection" of Private Palestinian Libraries in West Jerusalem,' Mita'am, A Review of Literature and Radical Thought 8 (2006): 12-22.

[15] Rona Sela, 'Pictorial History of Palestine,' Theory and Criticism 31 (2007b): 302-310.

[16] Violence is part of the colonial situation as many scholars demonstrate. For example: Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, trans. Constance Farrington (New York: Grove Press, 1968); Albert Memmi, Decolonization and the Decolonized (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006).

[17] The topic is also at the heart of other research studies: Ariella Azoulay, for example exposes the physical violence reflected in various archives, not only Israeli but also Palestinian and foreign: Azoulay, Constituent Violence, 1947-1950.

[18] Aspects of this nature are expressed in other colonial countries, such as in postcolonial archives in South Africa, mentioned earlier. McEvan, 'Building a Postcolonial Archive?'

[19] Walter Benjamin, 'Critique of Violence,' On Violence: A Reader, eds. Bruce B. Lawrence and Aisha Karim (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007), 268-285.

[20] Allan Sekula, 'The Body and the Archive,' 10-11.

[21] Joseph Pugliese, 'Abu Ghraib and Its Shadow Archives,' Law and Literature 19.2 (2007): 249-261.

[22] Sela, Photography in Palestine.

[23] Sela, 'The Absent-Present Palestinian Villages' and Sela, Made Public.

[24] Arnon Golan, 'The Capture of Arab Lands by Jewish Settlements in the War of Independence,' Cathedra 63 (1992): 122-124.

[25] Benny Morris, The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem, 1947-1949 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004).

[26] In 1948, the new Israeli state closed its borders to the Palestinians who wished to return to their homes and expropriated their houses in towns and villages, declaring them 'abandoned property'. In March 1950, the state regulated the subject in the framework of the Absentee Property Law designed to prevent Palestinian refugees from claiming their property. Instead of Abandoned Property the property became Absentee Property. 'Absentees' Property Law 5710 - 1950,' Israel Law Resource Center, February 2007.

[27] 'Village files' was an organized pre-state Jewish military intelligence gathering about targets – mainly Palestinian villages, but also police stations and military camps. It was carried out mainly by Jewish scouts, volunteers and information officers of the Haganah from 1943 to 1948 due to lack of information for operation planning purposes and for future occupation of the villages. The system was based largely on visual gathering – photography from the ground and from the air, drawing, sketching and mapping. Its main purpose was to learn how the villages were planned and structured, the main roads, landscape and topographical data. In the same period (1940-1948) very detailed textual surveys were prepared about the villages by a separate body of the Haganah, SHAI (The Intelligence Service). They included extensive information about the villages and their population: historical, agricultural, demographical, architectural, social, economic, military, education, families and leaders, etc; as well as main roads that lead to the villages, water sources, the village's topography and the like... Early studies on the subject don't differentiate between the two methods: Ian Black and Benny Morris, Israel's Secret Wars: A History of Israel's Intelligence Services (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1991), 24-25 and 129; Meron Benvenisti, Sacred Landscape, The Buried History of the Holy Land since 1948 (California: University of California Press, 2002), 70-71; Ilan Pappé, The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine (Oxford: Oneworld, 2006), 17-22.

Yoav Gelber was apparently the first to distinguish between the surveys and the 'village files' but at the same time wrote that they were both taken by SHAI, which was not the case: Yoav Gelber, The History of Israeli Intelligence, Part I: Growing a Fleur-de-Lis: The Intelligence Services of the Jewish Yishuv in Palestine, 1918-1947 (Tel Aviv: Israel Ministry of Defense Publications, 1992) 329-330 and 526-527. The confusion between the two methods was indicated in: Shimri Salomon, 'The Haganah's Arab Intelligence Service and Project for Surveying Arab Settlement in Palestine, 1940-1948,' A Sheet from the Cache, Quarterly Bulletin of the Haganah Archives 3 (2001): 9-10. See also: Yitzchak Eran, The Scouts (Tel Aviv: Israel Ministry of Defense Publications, 1994); Sela, Made Public; Shimri Salomon, 'The Village Files Project: A Chapter in the Development of the Haganah's Military Intelligence, Part 1: 1943-1945,' The Haganah Research Pamphlets 1 (2010).

[28] Sela, Made Public.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ibid., 53-56.

[31] When I searched the Haganah Archive in early 2009, I found hundreds of photographs of this nature. Now, when reviewing the archive once again, there were only a few dozen of them (mainly those I scanned for Made Public). It's not clear whether they disappeared accidentally after publication of the book.

[32] It will join other sources of information such as Walid Khalidi's important book All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948 (Washington DC: Institute for Palestine Studies,1992) and other sources mentioned in his book, and Salman's Abu-Sitta's extensive Atlas of Palestine (London: Palestine Land Society, 2004) that used Israeli sources in a limited way. Efraim Karsh claims that Khalidi overlooked the 'village files' and the air-photographs as sources for his book All That Remains. See: Efraim Karsh, Fabricating Israeli History: The 'New Historians' (New York: Routledge, 2000), 12.

[33] Derrida, Archive Fever, 15-21.

[34] McEwan, 'Building a Postcolonial Archive?', 742.