Interviews

Archives on Archives

Maryam Jafri in conversation with Stephanie Bailey

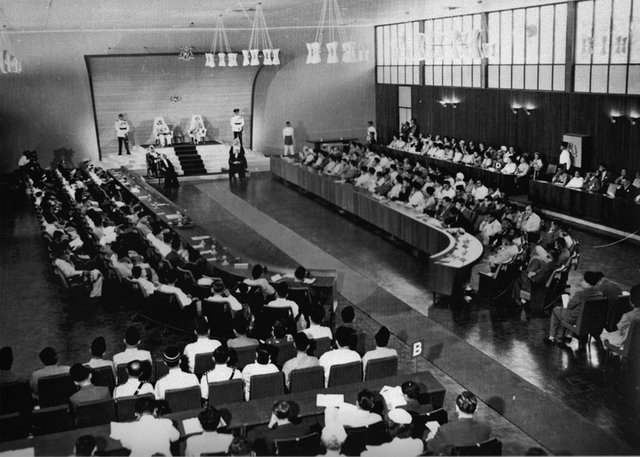

Maryam Jafri has long engaged with the archive. One of her projects, Independence Day 1936-1967 (2009-ongoing), comprises of 67 plus archival photographs mainly from the first independence days of various Asian and African countries (over 23), including Indonesia, India, Vietnam, South Vietnam, Ghana, Senegal, Pakistan, Syria, Malaysia, Kenya, Tanzania, Mozambique, Laos, the DR Congo, and Algeria. In this sustained investigation into archival documentation of such foundational moments in the history of what have long been referred to as the postcolonial nations, Jafri observed a number of similarities and differences contained within the aesthetics and the forms of such momentous events.

Within the framework of Platform 006 and the theme of the archive, this interview with Jafri starts with the Independence Day series and expands into her practice as a whole, and the various projects that have and do deal with the archive both as a concept and a material reality.

Stephanie Bailey: One of your most extensive projects is Independence Day 1936-1967 (2009-ongoing), could you talk about this series?

Maryam Jafri: The photo series Independence Day 1936-1967 (2009-ongoing) comprises my most sustained investigation of the archive. A key concept of the work is that, whenever possible, the images come from archives located in the countries themselves, so you can see why I needed to make it an ongoing work! So far, the work draws upon over 27 archives located in 24 different Asian and African countries. A partial list includes Kuwait, Tunisia, Algeria, Jordan, Benin, Kenya, Mozambique, Ghana, Indonesia, India and Malaysia. Some people have asked why I don't just go to Paris or London, but, whenever possible, I try to avoid the old imperial centres, and instead examine how a given Asian or African nation state is preserving the foundational images of its own coming into being.

Of course, sometimes there is no alternative to using a western archive, due to a current or past political situation. For example, South Vietnam no longer exists, and you only find its Independence Day images in archives in the United States, either in the Library of Congress or Corbis. Vietnam obviously hasn't kept those images – or if they have them, they're not telling. Also, back in 2009, I managed to obtain some interesting Syrian Independence Day images from a couple of archives in Syria, including the National Museum. But now of course that would be impossible.

SB: And the series is ongoing…

MJ: As you can imagine, I have 100s of images, most of which don't make it into the final installation but that are important resources in their own right, and a book format allows a different view onto this material than a photo installation, obviously.

I am also now in the middle of negotiating access to another up-until-now obscure archive that has been largely hidden from public view. The restriction of access to this archive is not due to security viewed as a means to generate scarcity and then sell that scarce information at a premium to a few well-paying corporate clients, copyright issues are also at stake. The archive is also very different visually and in subject matter from the archives used in Independence Day 1936-1967. This one focuses solely on the USA, but it too is an obscure archive, albeit intentionally obscured due to reasons of economy rather than geography. I can't say more because it is still in development, and also because, after months and months, I have pried a tiny crack open – and I'm thrilled about that – but I am still in the middle of trying to fling open the door to this up-until-now secret vault – treasure trove, really – of American popular history.

SB: With the Independence Day series, the images you have collected and assembled reveal how modern, postcolonial nations have, in the process of becoming independent, often adopted the same political aesthetics – and indeed systems – of their colonizers. The ceremonies and parades appear similar in aesthetic and format: the uniforms, the processions, the cars even, which visually reflects a kind of wholesale adoption of western political systems produced in and out of the colonial period. Can you talk about what you learned from this project through the assemblage of these images, and what they say about a nation as an archive in its own right, in that political systems themselves are embedded within very complex and material histories formed – in part – from occupation?

MJ: Independence Day 1936-1967 is about relations – not biographies – of individual countries; it's about comparisons, flows and symmetries. Perhaps that is where collating, sorting and collecting come into play, since archives are usually bound by personal or national frames. But Independence Day 1936-1967 represents material selected from over two dozen archives and made into a second order archive – an archive of archives: a collection of collections.

The political aesthetics reflect the political realities as well as the past, present, and future of these new nation states. Violently inducted into western modernity by colonialism, there is no debate or discussion, no possibility even on the mental horizon of the colonized – whether they are revolutionaries or colluders – that anything other than the nation state is the logical outcome of their struggles. The ability of the western colonial powers to shape the very horizons of what is and what is not imaginable is perhaps their greatest triumph – and at the very moment their power is allegedly waning. The Independence Day photos of a country born of a revolution like Algeria or Indonesia or Mozambique look very different from the Independence Day photos of Kuwait, for example, or Jordan, for that matter. Those differences are important, and are addressed in my work, but the paucity of imagination with regards to the final outcome of their struggles – the nation state – is striking, because rather than, say, agitating for political formations reflecting interests and realities on the ground, we have a one-size-fits-all solution implemented, without regard to geographical, historical, or cultural specificities.

This shouldn't be a surprise; it isn't. But to see the actual photographic evidence of this is still very powerful. Efforts to implement more regional or strategic solutions do eventually emerge, such as the United Arab Republic, and the Non-Aligned Movement; and of course these developments are rightly feared and immediately shot down by the former colonial powers – the United States, the USSR, and various regional colluders.

SB: Have you found differences in the way the Independence Day series has been read, depending on the context in which the images are shown?

MJ: Well I have to say, this is a work I've shown quite a bit, and it seems to function well in different contexts. But some of the strongest responses have come from showing the work in countries that have themselves recently undergone independence struggles, or where it's still very much a topic – Romania, Taiwan, and Croatia, for example. When making the work, a key point was that no one viewer should be able to recognize all the images – an Indonesian or Dutch person will recognize Sukarno but perhaps not Rochas; an Indian or English person would recognize Nehru but perhaps not Atassi. And yet, even if you don't recognize the specifics of person, place or time, the solemnity of the occasion still communicates itself to the viewer, and thus there remains an awareness that the photos are documenting something of significance. It is not an orderly march of 'History', but rather the messy and chaotic stumblings of dozens of overlapping histories.

SB: Thinking about overlapping histories, in The Siege of Khartoum, 1884 (2006) you take images from the Iraq War in 2003 and combine them with archival documents from other points in history, from the nineteenth century onwards. Then there is another, more recent work you produced, Global Slum (2012), in which you present, in one section, the security apparatuses of schools, hospitals and prisons as sites for S&M role-play within the context of 'economy'. Could you expand on the ideas behind these works, and how they relate to the concerns of your practice as a whole?

MJ: Siege of Khartoum, 1884 is a series of 28 posters; each poster combines an iconic image from the Iraq War, or the 'War on Terror', and juxtaposes it with a news article that seems to correspond to the image, but that in fact comes from an archival newspaper article about an earlier imperial intervention in the Middle East, Vietnam, Panama, the Philippines and so on. In each case, the headline and the text seem to perfectly describe the image, but in fact the article originates from some earlier intervention in either American or British history. I often made use of archives from British newspapers describing British interventions in the Middle East because in the post-World War II era, the United States positioned itself as the logical inheritor of the decaying British imperial order in that region, and thus inherited much of its language and its way of narrativizing its imperial forays from the British (while simultaneously disavowing the fact that it had imperial ambitions).

Global Slum is a photo/text work that explores nine sites in four different continents, all of which are situated at the interface between role-play and economy. The section you refer to – Schools/Hospitals/Prisons – comes from various S&M dungeon theme rooms that are meant to mimic one of the above three institutions: a schoolroom, a medical examination room, an interrogation chamber etc. Global Slum maps a history and geography of new forms of labour – affective labour in the case of the S&M theme rooms – and posits a continuity between material and immaterial labour, between Fordism and post-Fordism, arguing that the post in post-Fordism is not a temporal index but a spatial one. In other words, factories have not disappeared but rather have been displaced in the 'Global South', and our current economic order rests on making that rather obvious (but often forgotten) connection as invisible as possible.

SB: In all of the works we've discussed there is a clear interest in infrastructure, systems and apparatuses of security. There are ideas of industrialization, nationalism, modernity and statecraft redolent in the Independence Days series, for example, or in Global Slum, with the S&M section, which invokes, for me at least, Foucault's appropriation of Jeremy Bentham's panopticon to discuss ideas of power and control in Discipline and Punish. What led you to explore such ideas in your practice?

MJ: My works often explore the interface between external systems of control and individual agency. But that interface works both ways; in other words, power flows both ways. Foucault was the first to note that power is productive, not simply negative; its effects can be felt in ways that are rational, even pleasurable, and there are always ways that power can be deformed, deployed in ways unforeseen or unintended, consciously or unconsciously. Put another way, to loosely quote Deleuze and Guattari, how or why do people seem to desire the very structures that imprison them, and how is that desire often felt in ways that are pleasurable, rational, inevitable or liberatory? And yet that doesn't mean we should be fatalistic; some structures are less oppressive than others and some struggles are more meaningful.

SB: In your work, the archive as construct, idea and metaphor is not only interrogated from a macro-perspective (systems, politics, history), but from a personal, micro perspective. In your video Staged Archive (2008), you dramatize a kind of judgment day; a man in a courtroom is confronted by spectres from his past and certain suppressed memories. You state how the genre of travelogues, which reached its height in popularity during the Victorian era until it petered out by World War II, formed a background to this work. The archival images you use in the film depict mobile cinemas from the National Archives of Ghana, which were favoured by colonial missionaries as a means to teach the Bible. Here, you have the subject placed within an archival space that is far from comforting, and which presents memory as something haunted, strange, dreamlike and nightmarish; something that resides in both a personal and judicial space. In this layering, then, would you say that the work uncovers hidden histories, while also delivering a critique on the archive as a narrative construct?

MJ: A subject as complex as the archive is best interrogated via diverse, sometimes opposing, perspectives, and across multiple art works. Furthermore, the tools most often used to unpack the archive – video, film, photography, lecture-performance – bring their own medium-specific histories to bear upon the resulting art work. With Staged Archive I found the original documents themselves highly theatrical, mysterious and dreamlike. The images are depicting the first time or one of the first times a group of people encounter cinema, and, as we know, when people first saw Hitchcock's Psycho in the United States, for example, they ran out of the cinema screaming – it created a riot. So imagine the Passion of Christ, with all its blood and gore, parachuted into a completely different cultural context. Sekula and others have eloquently analysed the archival impulse in relation to technologies of power, and it is something that always needs to be thought through by artists working with the archive.

But my specific criticism stems more from seeing how solidified the tools to unpack the archive seem to have become, particularly the colonial archive: documentaries with ponderous voice-overs and/or a morass of information, presented in vitrine after vitrine, and accompanied by reams of text. What seems to be missing are more abstract forms of dealing with the archive that expand its space, rather than simply decoding its meaning. However, as noted earlier, I myself have employed contradictory approaches, depending on the source material, so the above statement is also contingent on the specific situation, the specific archive, or specific questions the artist wishes to address.

MJ: When working on Independence Day 1936-1967, I primarily utilized archives in the countries themselves, which means I know those archives quite well. One day, relatively recently, I randomly decided to check the Getty and Corbis websites and see what they had. To my shock, I saw some images that I had already obtained from the Ghana Ministry of Information, but which Getty claimed to own – the exact same images. And these weren't just random images of a landscape or a village, but foundational images of that nation's history. In the work, I trace how Getty and Ghana, independently of each other, copyrighted the same images, and I also analyse some discrepancies in Getty's captions and dating of the photographs, and the consequences of those discrepancies.

As artists we are always dealing with copyright: it's a real headache – moreover, a lot of the curators I know say that when attempting to include historical photographic material, a large portion of their budget can often go on fees charged by these corporate image banks, who own just about all the iconic images of the twentieth century. And let's remember that Getty in particular is one of the most active enforcers of copyright, so I was curious to see how they came to claim exclusive ownership of these images.

There have been a lot of great exhibitions and art works focusing on the archive, which I have found very inspiring. I wished to specifically address the question of who owns and controls the images popping up in all these show – it seemed as important to address as the repressed or hidden histories these images allegedly document. So with the entire 'Versus series' – Getty vs. Ghana, Corbis vs. Mozambique and Getty vs. Kenya vs. Corbis – there is, on the one hand, a public archive located in a postcolonial country, with actual photographs stored in an often hard to find physical location. Then, on the other hand, there is a private image bank, located in cyber space but headquartered primarily in the United States, with information stored in digital format and with an army of lawyers, marketing agents, sales agents, computer programmers and so on ready to enforce their ownership over what are often collective histories.

One important thing to keep in mind also is the question of access – or rather, ease of access – to these images. For example, 2007 was the fiftieth anniversary of Ghanaian independence, and I noticed that some blogs and even online newspapers from Ghana linked to the Getty website, with Getty's version of the independence images. So Getty was able to represent this iconic moment of self-determination to the very people from the country in question.

SB: This idea of Getty controlling or representing this moment, as you say, brings me back to the reason why I became so interested in the Independence Days series and your work in general. In your practice, it seems you represent the infrastructures of modernity and its political and social systems through the investigation into collating, storing, and even reading historical documents through the archive, which essentially comes to constitute a nation's history, even its identity. How do you see your practice developing as the twenty-first century unfolds, and, in turn, how do you see the archive, both in its function as a repository of history and as a form in and of itself (a narrative or assemblage), evolving in tandem?

MJ: I have worked extensively with the infrastructure of modernity as you note, and it constitutes a key strand of my practice. I am also increasingly drawn to social histories – how politics is embedded in the everyday, through a seemingly obscure topic such as garment production for the fetish industry (as in my moving image work for Manifesta 9, Avalon) or through food – specifically the industrialization of food production, which began in the early twentieth century. My interests are quite diverse. In terms of the archive, the transformation of collective public images into for-profit information reflects the broader trend that the Internet has offered us, simultaneously opening the world up in terms of sheer volume and ease of access to some information, and paradoxically concentrating power in fewer hands.

To see the Platform Response produced by Jafri, featuring images from the Getty vs. Ghana series, follow this link.

Maryam Jafri is an artist working in video, performance and photography. Informed by a research based, interdisciplinary process, her artworks are often marked by a visual language poised between film and theatre and a series of narrative experiments oscillating between script and document, fragment and whole. She holds a BA in English & American Literature from Brown University, an MA from NYU/Tisch School of The Arts and is a graduate of the Whitney Museum Independent Study Program. She lives and works in New York and Copenhagen.