Reviews

Everywhere But Now

The 4th Thessaloniki Biennale

How does one make something that is beyond repair new again? Such questions resonate in Greece today, after eight years of recession and as the country's infrastructures – including its public institutions – continue to suffer. The night before the 4th Thessaloniki Biennale opened on 18th September 2013 (through to 31st January 2014), with a central exhibition curated by Adelina von Fürstenberg, a 34-year-old man was killed. He was a hip hop artist, a known anti-fascist, stabbed in Athens by a member of Greece's far right Golden Dawn party, which models itself on the Nazis. It was but another low in a country that, one might argue, has still to reach its lowest point. And so, as the Thessaloniki Biennale opened, the question was raised again: how might Greece become new, now? For many Greeks, there is no point in asking the question – the only option is to leave, hence the timeliness of von Furstenberg's title for the 4th Thessaloniki Biennale's central exhibition: Everywhere But Now.

Perhaps this is why the 4th edition of the Thessaloniki Biennale is a nuanced, sensitive curatorial that illuminates the context of Thessaloniki itself, produced from an assemblage of works – old and new – by 50 artists from 25 countries, from Brazil, Cuba, Iran, India and all over the Mediterranean region, brought together to produce a message rather than a statement. It is a message invoked in a video installation by Rosana Palazyan, produced especially for the biennial – A Story I Never Forgot (2013). It traces Brazilian born Palazyan's Armenian grandmother's journey as a refugee in Thessaloniki (where she became an embroidery teacher in an Armenian embroidery group with the support of the Armenian General Benevolent), to her eventual landing in Brazil. This journey is embodied by a handkerchief Palazyan's grandmother carried with her from one end of the world to another. To Palazyan, this handkerchief is not only a relic of a specific historical moment – and legacy – that has in turn shaped her own contemporary identity. It is a message in a bottle – an object that stands for every instance of displacement and human suffering caused by the unspeakable cruelties of war, displacement and genocide. Of course, Thessaloniki itself is no stranger to such experiences – the Balkan Wars and the great population exchange of 1923 being two cases in point, not to mention the current exodus engendered by a very twenty-first century economic crisis, a situation that has brought another kind of violence upon Greece and its people, namely, the destruction of society and its civil institutions.

Thus, it is through such works as Palazyan's that Thessaloniki's historical position as a crossing point has been resurrected. This is an important move, given Greece's growing global isolation: a painfully ironic development given the long and historical relationship this country, not to mention the Mediterranean region, has had with the world at large as told across the annals of history. Multiple layers have thus been rekindled and remapped to produce reflections on common experiences and shared stories. In this light, the biennial locations are as important as the artworks. The archeological museum (showing David Casini) and the Museum of Byzantine Culture (showing Adrian Paci) have been used, as have the Macedonian Museum of Contemporary Art (showing Jacques Berthet and Sheba Chhachhi) and the State Museum of Contemporary Art (showing Bill Balaskas, Paris Petridis and Panos Tsagaris), which houses the Costakis Collection – one of the largest collections of Soviet avant-garde art in the world amassed when Costakis was a driver for the Greek embassy in post-revolutionary Russia. Then there is Yeni Camii, a mosque built by an Italian architect in 1902 for a community of Jews who had converted to Islam in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (showing Haris Epaminonda, Hüseyin Karabey, Jafar Panahi and Rosana Palazyan and Gal Weinstein), and the Alatza Imaret, a fifteenth century Ottoman mosque.

The latter two spaces produce the most contextual impact as architectural relics attesting to Greece's cultural relationship with the Ottoman Empire and its legacies. This was underscored in October, when the Turkish government requested the removal of Ange Leccia's video of a naked Laetitia Casta submerged in water, Nymphea (2012), from the Alatza Imaret (also showing works by Gülsün Karamustafa, Beforelight, Mark Mangion and Peter Wüthrich), after complaints were made against the work's content by Turkish visitors during the Eid al-Adha holiday (though Alatza is no longer used as a mosque).

The final space, Pavilion 6, is where a majority of the works in the biennial are on show, which includes pieces by artists including Khaled Jarrar, Raed Yassin, Desertmed Collective, Los Carpinteros and Deanna Maganias. It is located on the site of the Thessaloniki International Trade Fair (the first time this location has been used as a biennial site). The complex itself is evocative of those built for World's Fairs in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, with the International Trade Fair at Thessaloniki having been established in 1926. Yet, as this biennial runs, the complex stands almost empty and seemingly unused, like a failed symbol of misplaced modernity – arguably the very 'thing' that unites us all in the twenty-first century, regardless of nation or nationality.

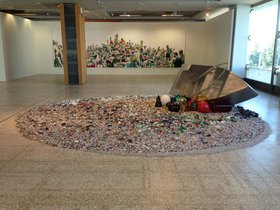

In this, there is a distinctive narrative to a grouping of works within the Pavilion 6 space. In the context of Thessaloniki – where Greece's northern border leads to Africa, the Middle East and Asia – Maria Papadimitriou's Anti-Apparatus (2011), a metal rowing boat semi-over-turned in a circular 'sea' of broken murano glass, immediately reflects on the issue of migration within the region, given the fact that since 2003, Greece has been a hotspot for illegal border crossings into Europe. At the same time, the sea of murano glass and its connotations to Venetian trade in such glass from around the thirteenth century onwards to Europe, the Mediterranean region and beyond, attests to the migratory waves that have driven the histories of civilizations, predicated in many instances on trade, and arguably continuing up to the present day. (Murano glass is still popular, after all.)

Yet, what also emerges from Papadimitriou's work, and what ties together the works in the central exhibition's curatorial in general, is another linking thread – the sea itself: the body of water that both unites and unties land and people. Near to Papadimitriou's boat is John Armleder's series of seven surfboards, Opar 7 (2007), which further attests to the constant movement that has been made across the Mediterranean seas throughout history – out of pleasure on the one hand (trade and leisure) and necessity on the other (resources). Indeed, taking into account Liliana Moro's set of five bronze dogs in battle, Underdog (2005), the history of this region has been a bit of a dog fight: a place of turbulence and turmoil, but also – and ironically – friendship and play.

And within this region of complexity and fluidity, there is the human experience – common yet fragmented, as expressed in Marta Dell'Angelo epic painting La Prua (The Prow) (2009), in which a clustered and colourful composition of people on a beach becomes, by association, a human pyramid of globalization. In the work, a Chinese girl stretches out her arms, while North African women sit amongst European bathers. As is usually the case on a crowded beach, the figures appear indifferent to one another, which may as well sum up the collective global experience of interconnectedness as it stands. Dell'Angelo's painting reflects on the global population as a colourful albeit chaotic mass: at once bound by the endeavours of history and their consequences – our political institutions, the economic system – yet ironically, also connected by the disconnections produced from the failures of the institutions these historical endeavours spawned.

In this, one work at the 4th Thessaloniki Biennale is clearly at the heart of the theme. In a 20-minute video titled Poet/Mourner (2012), Nigol Benzjian presents a pared down version of a longer lecture by Marc Nichanian, associate professor of the department of Armenian studies at Columbia University on Armenian poet Daniel Varoujan, one of the first Armenian intellectuals to be arrested by the Young Turks in 1915. In his lecture, Nichanian presents a thesis, through three poems by Varoujan – 'Vahakn', 'Among the Ruins of Ani', and 'To the Cilician Ashes' – which, for Benzjian, express precisely how poetry and art are the ultimate expressions of mourning and in turn, how the artist becomes the one who is left to pick up the pieces after a massacre. Viewing the 4th Thessaloniki Biennale in Greece just days after another life was claimed by the chaos spurned from the very political systems that were once designed – or at least entrusted – to serve the people. Maybe here, it could be argued that the necessity for art still has its case.

Take the question of whether or not to cancel the Thessaloniki Biennale opening celebrations, which took place the day after the politically-motivated murder in Athens. This reflected – to a lesser extent of course – the question of whether to cancel the 13th Istanbul Biennial. The fact that both biennials carried on, despite the difficulties they faced, while also both taking the step to open up to the public for free, was a positive move. After all, to know that some of our public institutions might survive in what is becoming a troublesome period in our shared global history, is perhaps the glimmer of hope we all need when the future looks hopeless. Is this why, more than ever, we need art, everywhere, now?

Thinking about Zineb Sedira's evocative image The Lovers (2008) – two broken ships leaning on each other in an open sea, immobile yet supporting each other – also presented at Pavilion 6, there is something hopeful in how both the Thessaloniki and Istanbul biennial exhibitions carried on this year, in spite of their seemingly 'hopeless' situations and criticisms against both that they are out of touch and part of the problem. Yet, perhaps we might derive some comfort knowing that these public vehicles, as fractured as they are, are still trying to provide at least some support to their publics, given it was for the public these institutions were initiated. If only the same could be said for other public institutions.

Read Omar Kholeif's review of the 13th Istanbul Biennial here.