Essays

Occupying the Occupied

Perceptions of Occupation and Control in Cyprus

The history of Cyprus is a fraught one: the Mediterranean island has been a site of occupation and control for hundreds of years. Istanbul-based curator Basak Senova became engaged with the island's politics of division in 2010, when she and Greek Cypriot curator Pavlina Paraskevaidou devised a collaborative artistic project entitled UNCOVERED: Nicosia International Airport, which used the closed Nicosia International Airport as a site for investigating the mechanisms of control at work on the island – divided since 1974 and subject to a UN peacekeeping force since 1964 – alongside notions such as memory and commons.

The works and activities by artists participating in the UNCOVERED project laid the ground, Senova here argues, for the Occupy Buffer Zone movement that developed in late 2011 and which sought to occupy that which was already occupied. In an action that exposed the absurdity of the controls on the beleaguered island, these activities rendered disused public spaces public once more.

OCCUPYING THE OCCUPIED: PERCEPTIONS OF OCCUPATION AND CONTROL IN CYPRUS

It is important to understand that occupation is both physical and mental (preoccupation).

Paul Virilio[1]

The word 'occupation'[2] is essentially defined through the action of 'taking or holding possession or control of'; nevertheless, the same word is layered through an alternation of multiple occupiers within a same territory.[3] This has been the case in Cyprus since 1974, when a military coup by the Greek Cypriots with the support of the military junta in Greece was launched.[4] Turkey's subsequent response was to send troops to the island as a guarantor state and these troops have never left. It was then partitioned by United Nations mandate, and a buffer zone between North and South under the control of the UN was created. The island is now controlled by multiple but different authorities and the experience, along with the acceptance of occupation for the islanders, takes different forms. Such an experience denotes a prolonged and deplorably normalized situation as the island has been technically in a cease-fire for the last 37 years.

Cyprus has been subjected to occupation throughout its history, by the empires of the Hittites, Assyrians, Egyptians, Persians, Rashiduns, Umayyads, Lusignans, Venetians, and Ottomans.[5] Britain also occupied Cyprus in 1878 and annexed the island in 1914.[6] My first encounter with this history was through the UNCOVERED, Nicosia International Airport project.[7] UNCOVERED is a three-year (2010-2013) research-based art project, divided into two phases, and its areas of investigation are the issues stemming from the prolonged condition of the closed Nicosia International Airport.[8] With the UNCOVERED project, we sought to encompass the key concepts of 'commons', 'memory', and 'control mechanisms'. The abandoned avant-garde modernist building of the International Nicosia Airport, which has not been accessible since the island was totally divided in 1974, embodies a potential for the investigation of all of these key concepts. Located inside the buffer zone, the airport has been closed to the public and under the control of the United Nations for the last 37 years. The site is mainly used as the headquarters base of the United Nations Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus.

The project started as a collaborative one with the UN Goods Offices in 2010, and continued to take shape with an independent development team and a curatorial direction. In order to operate within the entire island, the structure of any act had to be bi-communal. My co-curator Pavlina Paraskevaidou is a Greek Cypriot who belongs to one the communities in the island, but as a Turkish national my part in this collaboration is totally opposed to the accepted scheme.[9] For any cultural project to be sanctioned, it must be run as a collaboration between Greek and Turkish Cypriots, or between Greeks and Turks, but not between an islander from either side and either a Turkish or Greek national. For this reason, I have not been recognized – or in some cases even semi-recognized – by the UN in official terms. Therefore, my national identity (regardless of my viewpoint) has always been considered a threat – not only by the UN, but also by various authorities and some individuals from the island. Nevertheless, this bizarre position has also helped me to collect, disseminate, and discuss the perspectives and realities of diverse positions in multiple formats.

During the course of the UNCOVERED project, either inspired by the Arab Spring and Occupy Movement or as the likely outcome of being silent for such a long time, there have been various demonstrations and protests on the island. In July, April, and October 2011, protests against statements made by Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan by Turkish Cypriots took place. Then, in July 2011, Greek Cypriots protested for several nights against their government after the blast in Evangelos Florakis naval base in Mari, which knocked out the island's main power station. A few smaller-scale demonstrations took place, against the presence of British military bases in Cyprus; against the drilling for oil and gas that was taking place off the coast of the disputed island; and against the North's proposals to build oil and gas storage tanks in the fields of Karpas, near the Yedikonuk village.

Nevertheless, the perception of occupation and the belated reaction towards the forms of it on the island has been only visible in the recent Occupy Buffer Zone actions. This movement has different intentions and motives than Occupy Wall Street or Occupy London, which are ostensibly protests against inequality, unemployment and homelessness. Occupy Buffer Zone, however, tends 'to protest and inform [about] the problems of the global economic and political system'; its priority is to attract attention to the prolonged Cyprus problem by criticizing all of the actors of the problem – including the UN.[10]

The UN's presence has never been loudly (or deeply) questioned by the islanders but can only be discussed within the UN's own pre-set terms and conditions. Yet, my experience with the UNCOVERED project also proved that in spite of the good and sincere intentions of the UN Goods Offices (and largely due to its own structural mechanism), the UN as an entity simply cannot allow for any diverse voice or discussion on the island.[11] Hence, some basic imperatives of control have been articulated and re-articulated by the public without question.

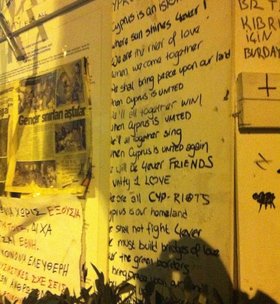

In this respect, Occupy Buffer Zone has been important in foregrounding the many voices on the island, regardless of the nationalities and ideologies of the protestors. They managed to utilize the buffer zone as an interface to express different opinions and discussions:

We have occupied the space of the buffer zone to express with our presence our mutual desire for reunification and to stand in solidarity with the wave of unrest which has come as a response to the failings of the global systemic paradigm. We want to promote understanding of the local problem within this global context and in this way show how the Cyprus Problem is but one of the many symptoms of an unhealthy system. In this way, we have reclaimed the space of the buffer zone to create events (screenings, talks etc.) and media of these events, which relate to the system as a whole and its numerous and diverse consequences. Opinions expressed in this manner are not necessarily of the entire group, only the umbrella points of reunification and solidarity with the global movement can be assumed to be.[12]

The protest movement began in October 2011 by Greek and Turkish Cypriot activists, in the Ledra/Lokmaci checkpoint, in Nicosia, Cyprus. It is one of the three zones that allow crossings only on foot and spans 80 metres. In November 2011, the occupation of the buffer zone became permanent.

UNCOVERED project's first exhibition was also realized in the same buffer zone, in an abandoned building belonging to the Kykkos Monastery. At that time, we managed to get permission from various authorities (such as the UN, both Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot police forces, militaries and so on) as well as from the Kykkos Monastery. The buffer zone was the natural location for an international (but also bi-communal) event, as it designates a 'non-place' or 'less-place', to use Marc Augé's term.[13] It is also considered to be the only place on the island that is politically/ideologically/culturally 'neutral'. What was very unique about this exhibition was not only the fact that we used an abandoned building, frozen in time since the 1970s, but also that we managed to use the crossing for installing Andreas Savva's work, which replicated the seats at Nicosia International Airport and placed them outside the venue in the buffer zone. These worked as the first seating units in the buffer zone. Accordingly, Savva altered the function of the Ledra/Lokmaci crossing from a transitory zone to a standard public space that people could spend time in. This alteration then expanded to become a site for Occupy Buffer Zone. The buffer zone is still a transitory place (and passageway) that people pass through but is now transformed to a public space of criticism and reflection.

Stavros Stavrides, who has published several books and articles on spatial theory by focusing on emancipating spatial practices, discusses in the UNCOVERED book that 'public space is indeed defined by the context which moulds its uses and social meanings but we need to understand context not simply as a state of things but rather as an ongoing process. Public space is always in the making.'[14] In this way, he underlines the fact that the public always has the potential to change and to be perceived as something else. This perception is invariably related to how it is defined and used by the public (the users); only then does the 'contest become[s] framed in a significantly different context'.[15]

In this context, the occupation of the buffer zone by the users of the buffer zone is not only ironic but also quite revealing of the overloaded and abnormal situation on the island. This frankly innocent and peaceful activity by a group of people in an area 80 metres long was perceived as a very serious threat by those controlling the buffer zone and the other authorities relying on this control mechanism.[16] In the same vein, an anecdote I heard from the protestors there unfolds an entire reading of such innocent activities and contemporary art by the authorities. In the following week of the permanent occupation in November 2011, UN officers approached the protestors and informed them that they could not do a bi-communal activity without the permission of the UN. The protestor's reply was direct and simple: 'It is not an activity, as we are occupying the buffer zone'. These conversations could lead us to long discussions about the usefulness and uselessness of art-related activities in politically charged situations. At the same time, one could also investigate the ways in which art could function as a strategy to underline what is not spoken. In this case, I believe that all the preceding cultural and art-related activities on the island prepared the ground for Occupy Buffer Zone. What they are achieving is the bringing together of people to discuss and question the situation, and this goes beyond the territories of the buffer zone. These protestors are also equipped to use social media and other communication channels: Occupy Buffer Zone does have a webpage/blog[17], radio station[18] and a Facebook page[19] and the protestors are connected with other activists all around the world.

This makes for an edifying example of what Saskia Sassen questions with regard to the function of connectivity when discussing 'the complex interactions between power and powerlessness' through the vectors of the worldwide uprisings:

How can the new social media add to functions that go beyond mere communication and thereby contribute to more complex and powerful capabilities for such movements? The rapid spread of Occupy initiatives across the United States and most recently extending to over eighty countries is one instance of such a multisited global formation that does not require direct communication, even when social media is a critical tool.[20]

The new social media – which was discovered long ago as a strategic tool by contemporary artists – is indeed the right tool for disseminating information and diverse voices without (or at least with a reduced amount of) censorship. In this respect, despite the economic, cultural and ideological bubble flying the contemporary art field, the UNCOVERED project shows that art can still be utilized as an information channel that can trigger social movements and even revolutionary motivations in some cases.

[1] Paul Virilio, The Administration of Fear, Semiotext(e) 10, trans. Ames Hodges and Bertrand Richard (Cambridge and London: MIT Press, 2012).

[2] See: http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/occupy.

[3] On 15 November 2011, Al Jazeera Television covered the story of Occupy Buffer Zone and interviewed Cypriot activist Mihalis Eleftheriou and Rahme Veziroglu, a Turkish Cypriot sociologist and activist. During this interview, Veziroglu stated that 'The word occupation is loaded with a lot of meanings for Cypriots. For the people living in the south, occupation refers to the North altogether. For some Turkish Cypriots, it means the military presence on the island. And then, there is also the ongoing occupy protest. When we combine them altogether, occupying the buffer zone which is occupied by the UN is pretty meaningful'.

[4] In 1878, Britain took over the government of Cyprus as a protectorate from the Ottoman Empire as a result of the Cyprus Convention. In 1914, at the beginning of World War I, Cyprus was annexed by the British. In 1925, following the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, Cyprus was made a Crown Colony. Between 1955 and 1959, EOKA was created by Greek Cypriots and led by George Grivas to perform enosis (union of the island with Greece). However, the EOKA campaign did not result in a union with Greece, but rather in an independent republic, The Republic of Cyprus, in 1960.

In 1960, the mostly Muslim Turkish Cypriots made up only 18 per cent of the Cypriot population. However, the 1960 constitution carried important safeguards for the participation of Turkish Cypriots in state affairs, such as the Vice President being Turkish Cypriot, and 30 per cent of parliament being Turkish Cypriot. One of the articles in the constitution was the creation of separate local municipalities, so that Greek and Turkish Cypriots could manage their own municipalities in big towns. This article of the constitution was never implemented by the Republic and President Archbishop.

Internal conflicts turned into an armed battle between the two communities on the island, which prompted the United Nations to send peacekeeping forces in 1964 and these forces are still in place today.

In 1974, Greek Cypriots performed a military coup with the support of the military junta in Greece and took control of the whole island. In response, Turkey sent its military to the island based on its rights as a guarantor state as per the 1959 Zurich Agreement. The military junta was defeated and the constitution restored but the Turkish military did not leave the island and seized the northern third of the island, prompting Turkish Cypriots in the south to flee to the north and Greek Cypriots in the north to flee to the south.

The de facto state of Northern Cyprus was proclaimed in 1975 under the name of 'The Turkish Federated State of Cyprus'. The name was changed to its present form on the 15 November, 1983. The only country to formally recognize 'The Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus' is Turkey.

In 2002, UN Secretary General Kofi Annan started a new round of negotiations for the unification of the island. In 2003, the UN-controlled demarcation line known as the 'Green Line' was partially opened by the North Cypriot authorities. The Republic of Cyprus allowed passage across the part of Nicosia it controls (as well as a few other selected crossing points), since the TRNC does not require a visa or leave entry stamps for such visits. In 2004, after long negotiations with both sides, a plan for unification of the island emerged. The resulting plan was supported by the UN, EU, and the USA. The nationalists on both sides campaigned for the rejection of the plan but it was accepted by the Turkish side while the Greek side rejected it. In 2008, the President of the Republic of Cyprus and leader of the Greek Cypriot community, and the Turkish Cypriot leader, agreed to restart negotiations under the auspices of the United Nations Secretary General.

This information was extracted and quoted by merging two online sources: http://www.uncyprustalks.org and http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Cyprus

[5] Andreas Sophocleous, An Introduction to the History and Geography of Cyprus (Nicosia: Nicocles Publishing House, 1997).

[6] Gail Ruth Hook, Britons in Cyprus, 1878-1914 (PhD. diss., The University of Texas at Austin, 2009) http://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/handle/2152/8381

[7] 'The Project,' Uncovered Cyprus website http://www.uncovered-cyprus.com

[8] The UNCOVERED project was initiated in 2010, based on Cypriot artist Vicky Pericleous's idea for an artistic intervention at Nicosia International Airport. Accordingly, in order to realize her idea, Pericleous worked on a project application and approached Özgül Ezgin (a Turkish Cypriot cultural manager, programmer, and artist) and Argyro Toumazou (a Greek Cypriot cultural manager and curator), who work on contract bases for the UN Goods Office. The UN Goods Office has been commissioning them to provide artworks for the conference room in which the peace talks have been taking place since 2009. Subsequently, her application was submitted as a proposal to the UNDP-ACT by Ezgin and Toumazou in parallel with the peace-negotiations process. Following the initial state with the UN, two curators, myself and Pavlina Paraskevaidou were asked to collaborate and develop a project for 2011. After working intensely together for about six months, we developed a long-term research-based art and media project that considers the UN initiation and the collaboration for 2011 as one of the segments of the project. Accordingly, the scale, the scope, and the structure of the project have been dramatically changed with the curatorial input.

The project was designed to have two phases in the span of three years (2010-2013). The first phase has concentrated on cultural production in Cyprus and the commissioning of eight projects by Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots, including Özge Ertanın and Oya Silbery, Görkem Müniroglu and Emre Yazgin, Vicky Pericleous, Erhan Öze, Andreas Savva, Zehra Sonya and Gürgenc Kormazel, Socratis Socratous, Demetris Taliotis, Constantinos Taliotis and Orestis Lambrou. The exhibition of the projects ran from 23 September to 23 October 2011, followed by a guided tour of the exhibition given by the curators and a panel discussion in the afternoon with Monica Griznic, Lamia Joreige, Niyazi Kizilyurek, Socrates Stratis and Jack Persekian, moderated by Basak Senova and Pavlina Paraskevaidou, and a screening of Anton Vidokle's New York Conversations. An accompanying book was published in November that year, including contributions by Stavros Stavrides, Bulent Diken, Alex Galloway, Abdoumaliq Simone, Jalal Touffic, Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Dervis Zaim, Mushon Zer-Aviv, Pelin Tan, and Socrates Stratis, together with essays from the curators and sections devoted to the archive and the artists' work.

The second phase gives priority to the commissioning and presentation of international art projects and publications under the auspices of UNCOVERED, both in Cyprus and abroad. We have presented the project in various different geographies with talks, presentations, and publications, and consequently managed to build bridges with some international institutions, artists and curators that would like to participate in the project. Therefore, with the second phase, the project links and compares communication patterns in different geographical regions and analyses and compares parallel situations across borders, by taking diverse political, economical, social and cultural backgrounds into account. In 2013, the project will be exhibited first at Depo in Istanbul.

[9] In other words, I am not simply from another country, I am specifically from one of the countries that happens to be a main actor in the conflict. I am considered to be one of the main occupiers. Please refer to: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cyprus_dispute

[10] See: http://occupythebufferzone.wordpress.com

[11] A day before the first exhibition opening of UNCOVERED, which was realized 'under the auspices of the UN' in September 2011, the exhibition was visited by UN executives, and Erhan Öze's work - which investigates the war of sovereignty over Cyprus via an electromagnetic field and the island's air space – was censored, along with the interviews with the islanders conducted by the artists in the 'archive' section. The explanation for this was the usage of the word 'Ercan' (the airport situated approximately 15 minutes from Nicosia but not internationally recognized as a port of entry). However, the project by Erhan Öze and the interviews were not promoting the airport; as the website of the project states: 'Öze investigates how the war of sovereignty over Cyprus has been extended to the electromagnetic field and the island's airspace. Oze highlights the tactic of intercepting radio signals as both Ercan Air Control Centre and Nicosia Air Control Centre try to exercise control over the FIR space and ascertain sovereignty. While he maps the airmisses over Cyprus' air space, he also presents interviews with air traffic controllers from both sides where each presents their side of the problem'. It was an unexpected act and a shock for us as the entire content was sent to the UN Goods Office in July 2011 and confirmed following the transfer of the first installment of the money allocated to the exhibition. Although the UN executives were quite sensitive not to call this action 'censorship' but rather a routine application of the UN regulations, the entire process and the logic of its operation clearly uncovered how the island is being controlled on multiple levels.

[12] See: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Occupy_Buffer_Zone

[13] Marc Augé, Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity, trans. John Howe (London: Verso, 1995).

[14] Stavros Stavrides, 'Public Space as Commons,' UNCOVERED Nicosia International Airport Book 1, eds. Basak Senova and Pavlina Paraskevaidou (Nicosia: Phileleftheros Publishing Group, 2011), 13.

[15] Ibid.

[16] As a note, since November 2011, the protestors have been squatting in the building that the UNCOVERED exhibition took place in and in April 2012, six activists were arrested in the buffer zone by anti-riot police and were taken to police headquarters for questioning. In the same incident, a British activist injured himself by jumping from the second floor of the building. He was transferred to a hospital. '"Occupy Buffer Zone"' Cyprus News Report, 7 April 2012 http://www.cyprusnewsreport.com/?q=node/5580.

[17] See: http://occupythebufferzone.wordpress.com

[18] See: http://www.radio.occupybufferzone.info

[19] See: http://www.facebook.com/OccupyBufferZone